The Screen Test • Joyce Chen

Bretty Rawson

BY JOYCE CHEN

I’ve never been one for New Year’s resolutions.

Not because I don’t believe in the psychology behind them – God only knows how much I am an advocate for self-reflection and self-improvement – but because I’ve always had a sneaking suspicion that New Year’s resolutions are actually made to be broken. The way they’re worded and thought about almost always sets the resolution-maker up for failure: “This year, I resolve to work out more” (meaning, what? Buy a new pair of running shoes and use them thrice instead of once?); “This year, I resolve to be a better friend” (read: respond to emails in two months rather than four); “This year, I resolve to spend more time with family” (but more time with family doesn’t mean a thing if you’re still plugged into a device while sitting in the same room, right?).

This may sound a tad bitter, sure, but to be perfectly honest, I only feel okay making these jabs because I’ve made these resolutions before, and by that same token, I’ve also failed at these resolutions before. There’s something exciting about starting a new calendar year that nudges our inner navel gazers awake to notice our shortcomings and attempt to remedy them with a promise to “be better.” But what I’ve come to discover over the years is that while New Year’s resolutions are always well-intentioned, they are often more about finding a temporary, band-aid solution to problems than actually digging deeper to get to the core of the issue.

A desire to work out more, for instance, might stem from guilt over poor lifestyle choices (ie. late nights, fried foods, overindulgence of all kinds), not an actual desire to exercise more. The resolution is less about running and lifting, and perhaps more about thinking about and taking control over our daily routines.

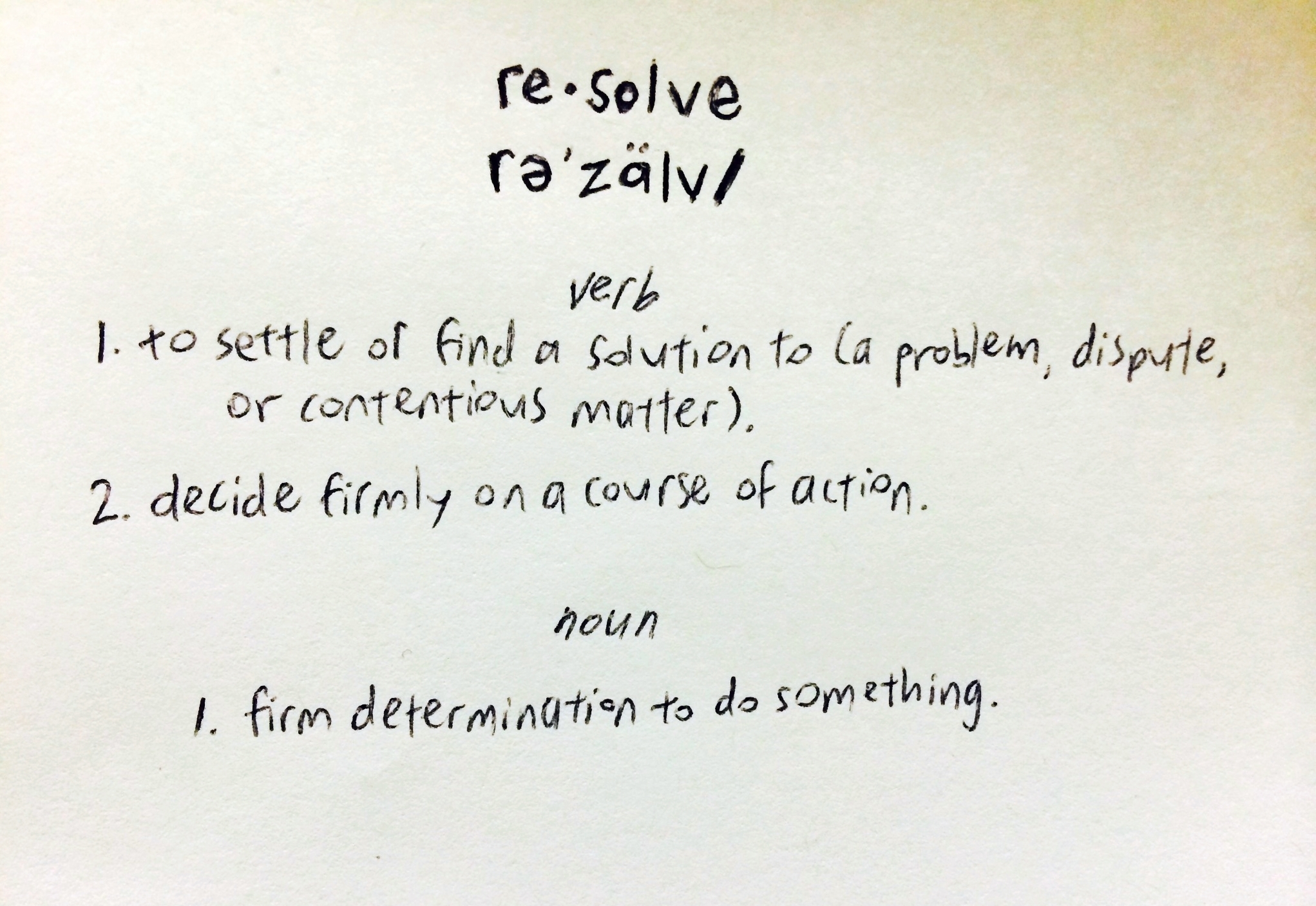

To that end, then, I would rather have resolve (n.) than to resolve (v.), because my goal isn’t to reach a conclusion right away; no, I want to understand my own process as it is unfolding. I would rather have the noun in my back pocket as a reminder than the verb in my front pocket, at the ready for a quick-fix solution. So this year, instead of a New Year’s resolution, I decided to have an anti-resolution. A plan to test my own willpower by opting not to do something that has become dangerously habitual to the point of dependency: stare at a screen all day.

I realize that as I am writing this, and as you are reading this, we are both staring at a screen – and that’s just fine. So to clarify, my decision to not stare at a screen is less a dramatic political statement and more a modified lifestyle choice, an experiment: Between the hours of 10:30 a.m. and 10:30 p.m., I allow myself to carry on as I always have – answering emails, scrolling through headlines, and laughing at silly GIFs. In those 12 hours, I feel connected to the greater community of the Interwebz, corresponding with friends halfway around the globe, pitching ideas to editors in other states, and engaging with a community beyond my immediate line of vision; I am in a digital portal and can free-float through both time and space.

And beyond the computer screen, I also allow myself to get lost in my iPhone, in the TV screen, in a number of other electronic means of communication; I express myself in words and emojis, and absorb new thoughts and ideas in the form of the news, news feeds, TV shows, Instagram, Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter. The sea of garbage, as a professor of mine once called this vast ocean of information, is alive and pulsing during those 12 hours.

This is what screens have given us, after all: a means to access other people, places, thoughts and head spaces, from wherever we happen to be at a given moment. And I am grateful for the distractions, as we all likely are, because that means that we can sometimes push aside the more immediate tasks at hand in favor of temporary escapes. But there is a threshold; there must be.

For me, that was last year, when I realized I was checking my email first thing in the morning and watching shows and films until I fell asleep at night. There was this feeling of dependency, of addiction, a light-bulb moment realization that I was literally spending all my waking hours as a slave to my many screens. I wasn’t getting good sleep, and I wondered sometimes if it was because my brain was going through withdrawal from not having a backlit device pointed straight at it during the hours I slept.

I realized that part of the problem with always being plugged into a device was that I was hop-scotching from distraction to distraction and was therefore not always quite here, the physical space I was occupying. And this meant, as a result, that hours and days and weeks and entire years were flying by without my ever having really experienced what was happening in the moment at the moment. I was living life in retrospect.

And that was a problem.

So though I still take part in the digital sphere between the hours of 10:30 a.m. and 10:30 p.m., these days, I’m opting to spend the hours prior to and after that off the grid a bit, focusing more on the who and the what of where I am during that time. Unplugging is the how. To experience life more vividly and fully is the why.

During those hours, I meditate and I think and I read and I write a lot (by hand, of course). There is a kind of stillness and peace I find in not being in front of or dictated by the influx of information found on a screen. It’s a feeling that I had long forgotten, and would most likely have continued to forget, if I hadn’t taken a step back and realized how my days had become inundated by thoughts and demands not my own. Being separate from the screen is giving me the luxury to do something I never thought I’d be able to do in this digital age: really hear myself think.

In the beginning, it was always tempting to cheat and take a quick peek through my phone in the morning just to see if there were any pressing emails or Facebook notifications or Instagram likes that took place overnight. But because I had given myself these rules and parameters, I felt a duty to keep myself in check, lest I disappoint myself with my own lack of willpower. I started to analyze that temptation, observe myself in third person during those morning handwriting sessions, and realized that much like Pavlov’s dogs, my instinct to check my inbox was more about the reward of attention (“so-and-so has replied to your email!”) and importance (“inbox: 52 from just one night? People really need to reach me”) than from an actual need to know information.

I am now finding that in those hours away from the screen, I am able to engage more fully not only with the present moment but also with myself, so that I know how to better navigate through the treacherous technological waters (and, to a certain extent, through social situations at large).

Now I write waterside, in cafes, in my room, in outdoor spaces that aren’t constrained by lack of wifi, outlets, or table-space. All I need is a pen, a notebook, and my fully focused mind. It is freeing.

Call it a reintroduction.

I feel more in touch with and honest with how I’m feeling because my thoughts are not as cloudy at the beginning and the end of each day, and I am starting to be able to translate some of that clarity into my daily living as well.

Call it a recalibration.

I sense myself being more selfish with my time and more careful in how and with whom I spend it.

Call it a reassessment.

The way I see it, we already segment our lives into so many distinct compartments based on how we spend our time anyway: family time, work time, free time, leisure time, personal time, social time, food time, sleep time, and on and on and on. So why not look for new ways to section off hours of the day, to break down previous habits and routines and build something new and perhaps, hopefully, more sustainable?

I’ve never been one for New Year’s resolutions because making them is, I think, a way to feel the thrill of a personal promise without any real commitment. Being more physically active, communicating more with loved ones, and reprioritizing our actions and activities are all noble pursuits, but what all three require above all else is a space and place to really explore the reasons why we want those things. And for me, I’ve found that space and place in my hard-won now, and I want to hold onto that feeling.

Every year, in place of a New Year’s resolution, I like to think of a single word to hold in my mind for those times throughout the year when I start to lose focus. In 2013, it was Create. In 2014, it was Trust. This year, 2015, I decided that my word would be neither verb nor noun, but a state of being.

In 2015, I have resolve: I am Awake

Joyce Chen is a handwriter in Brooklyn. She is also a journalist who thinks she spends too much of her time staring at screens - writing for print and the web, watching and reviewing films, and sending strings of emojis to family and friends. When she's not plugged into the World Wide Wonder, she can often be found out on unplanned runs throughout New York City, taking long walks along the waterside, or otherwise stretching her legs and getting out from the great indoors.