This is Where I Battle My Writing Demons • Sheila Lamb

Bretty Rawson

BY SHEILA LAMB

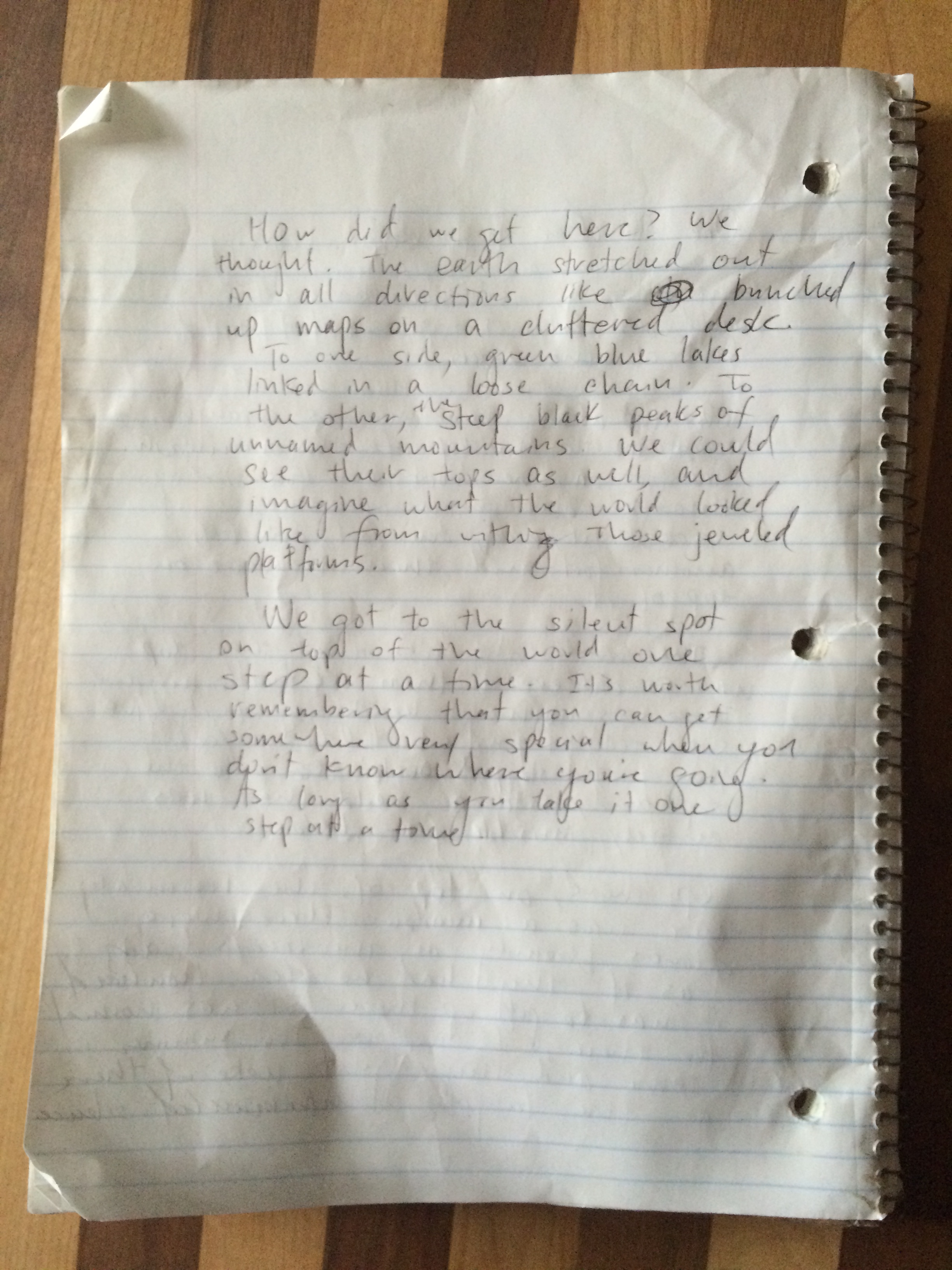

The first draft always begins on paper with ink. Sometimes, the first handwritten words are a line, a sentence, a phrase. Sometimes, a scene. Usually, these words will not be in the final story. But they mark the magical moment where the story began.

I find ideas flow better from paper to pen. When I handwrite, I write fast. Inspiration can be elusive and I want to get the words on paper without disruption. There is a smooth connection from pen to hand, something that, for me, pencils don’t give. Computers certainly don’t. The pen is, literally, a fluid implement. I favor gel pens (a Pilot G-2). It’s part of the whole flow of words, from thought to paper. I’ll use pencils in a pinch, but graphite tends to smudge and fade. There’s also a rub as the pencil hits the page, a dryness, a physical sensation, that gives me the shivers – like fingernails on the chalkboard. Occasionally, there is the issue of broken lead and the search for a pencil sharpener. Pencils, despite their simplicity, have too many complications and they are not my utensil of choice.

Ballpoint pens are another option. They are easy to find, ten to a pack. However, they are my second choice. Words don’t glide from a ballpoint as they do from a gel pen. Like the pencil, the ballpoint ink to paper has a palpable feel that is off-putting to me. Ballpoint ink can be thick and gloopy, and sometimes leaves thick globules at the end of sentences. Although ballpoints are certainly preferable to computer keyboards, they don’t have the smoothness of a gel pen.

*

Writing by hand is second nature to me. Perhaps because I’ve handwritten stories since elementary school, when they gave us green penmanship paper with fat, chunky pencils. I’ve kept paper and pen journals since high school. It’s easier for me to reach for pen and paper than trudge to the laptop, wait for it to start, find the folder, open the file, and pray the program doesn’t freeze or mysteriously return me to last week’s temp file draft. All those layers of technology slow the inspiration, that spark of a new story or pivot within a plot.

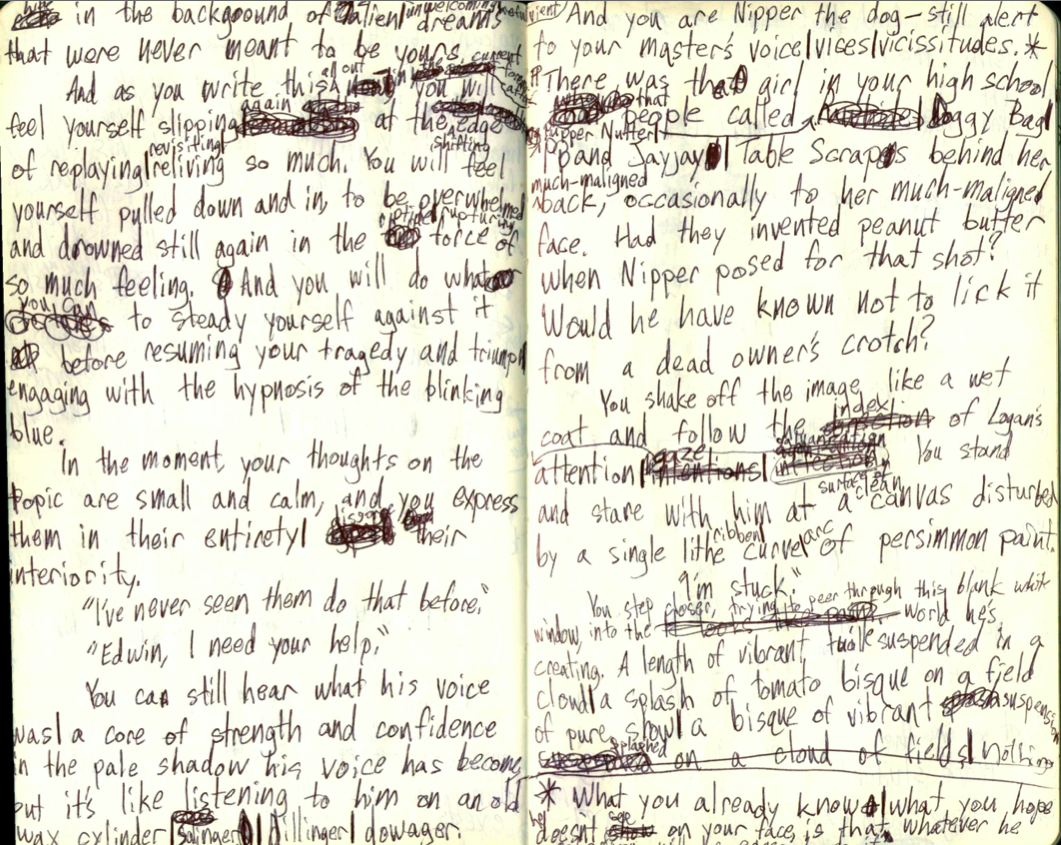

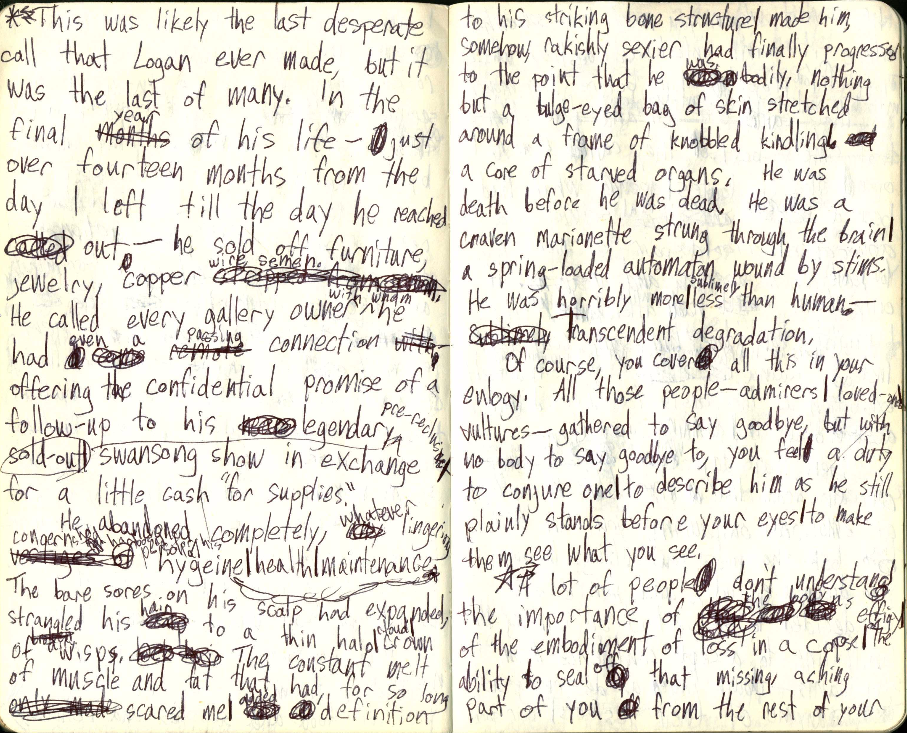

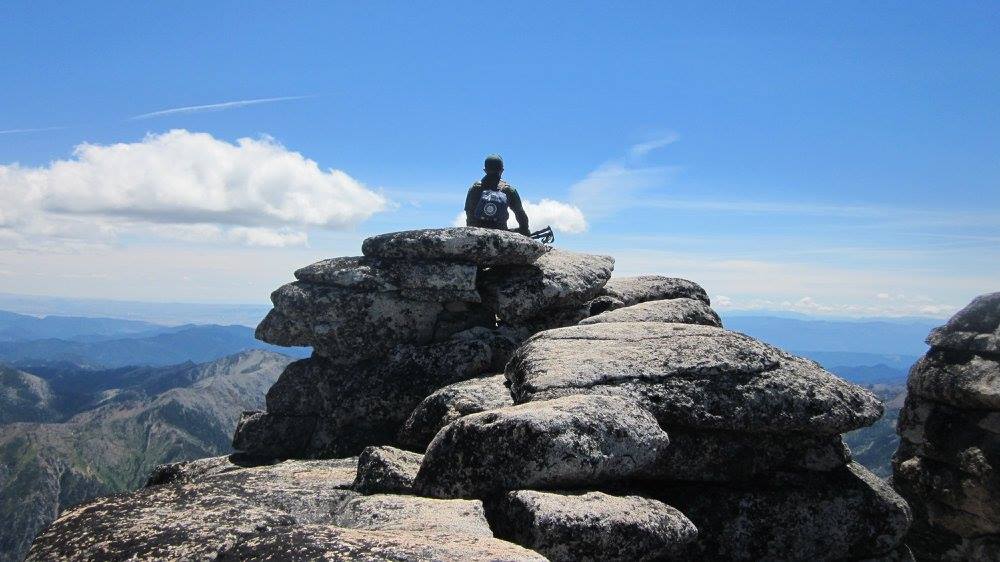

For short stories, I write the entire first draft — or what I think is the entire draft at the time — on paper. Most of it begins in my bedside journals. My recent story, “Hunger, Not Tame,” began after a camping trip to Assateague. I journaled about our trip and the feral horses. I was infuriated with the tourists, who petted and fed potato chips to the horses on the beach.

That incident was the scene that stuck, and the one that gave way to story. I began to play on paper, shifting from my journal to a spiral notebook — last-day-of-school perks of the teaching trade — expanding the scene into a story, in longhand. I witnessed Kate, the main character, grow from this exploration: a park employee who confronted the people tossing Doritos at the horses. I write until I come to what feels like a stopping point — the end of a scene or section of dialogue. If I’m lucky, I’ll discover the final sentence here. Something in the shape of the words lets me know that this is it — this phrase where the story will end.

*

In writing by hand, I’ve discovered that this is where I battle my writing demons. For me, past defines the present, so as a writer, I struggle with back-story. Actually, I revel in it. I spend a lot of time figuring out how my character made her way to the start of the story. I tend to develop psychology before I develop plot. Why is the character there? What makes her do what she is doing? Writing those back-story details by hand is necessary for me to create the character. I’m fine knowing many of those initial, raw words won’t make it into the next draft. The process paints a picture, so I know who I’m dealing with as I place her in situations she’d rather not be in. The potato-chip tourists barely made it into the final draft. Even though they were the beginning, in the end, they were a brief, two-sentence presence. They were simply a starting point for Kate to explain why she was at Assateague and what motivated her work. The longhand process, I’ve discovered, is a sort of third-person, in-character, journaling.

*

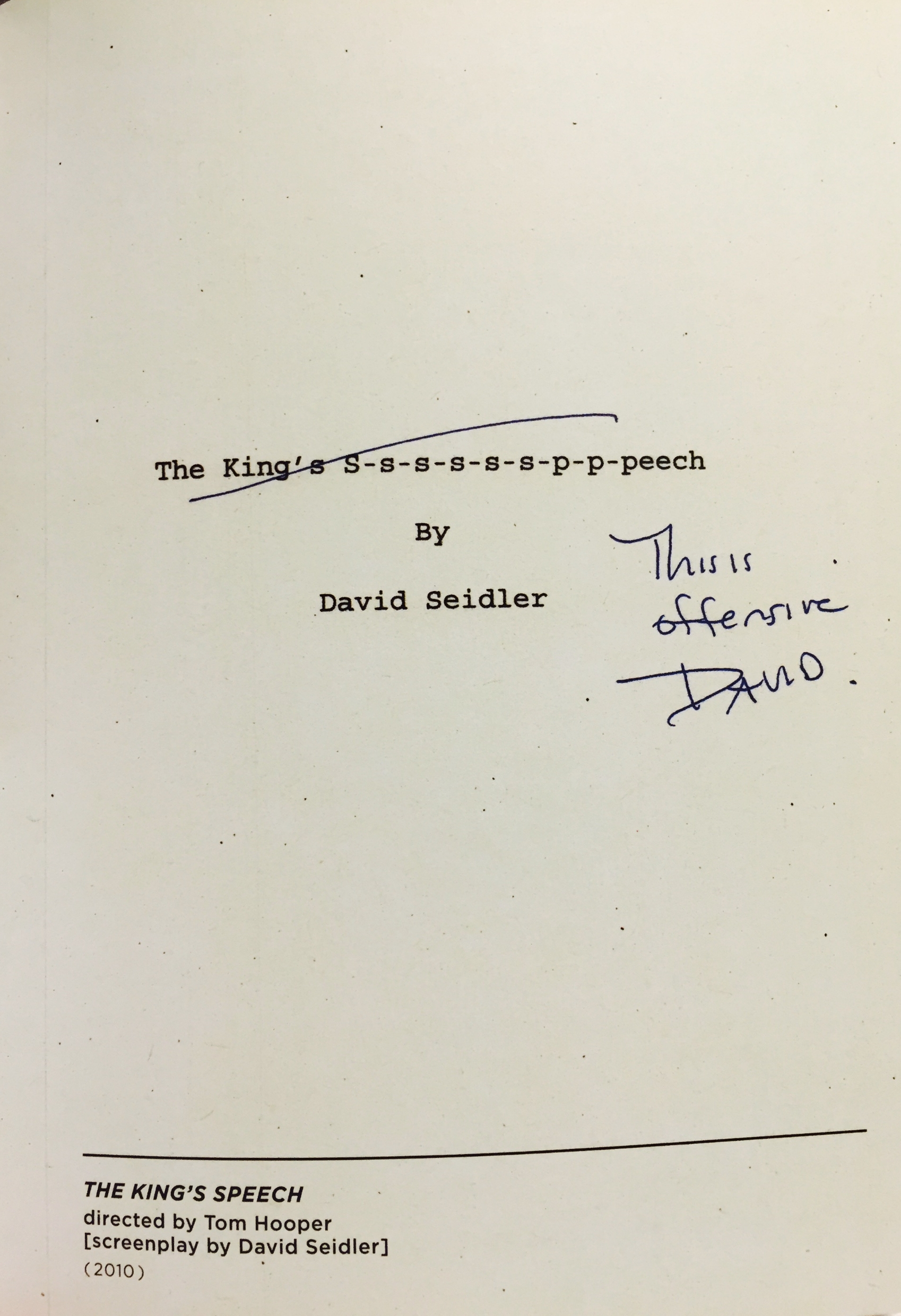

My conflicts with electronic writing are three fold: First, my creative energy, that burst that inspires a new story, vanishes when I start writing on an electric document. All of the green and red warnings that highlight misspellings and incorrect punctuation are like blaring sirens, taking me out of the story. Instead of writing, I go back and correct. That delete key is dangerous. It can very quickly disappear a phrase that might not fit in that sentence, but a phrase I may want to use later. Second, as I develop and revise the story, I prefer the kinesthetic, hands-on process of physically writing (educational researchers are looking at the correlations between student success and handwriting but I’ll save that tangent for another time). Instead of scrolling through track changes, highlights, and text colors, I make side notes on paper with the pen, underline an idea I want to develop, remind myself to go back and find a synonym, with a circle and the abbreviation: syn. The handwritten notes make the ideas and revisions stick. Finally, I’m incredibly distracted by the Internet. Turn off the Wi-Fi, a lot of people say. Yet the Internet is a necessary evil because many stories require research. I researched the feral — not wild — horses of Assateague, their history, and the park regulations, but the pull of social media is powerful. It is so easy to go from the National Park Service site to Facebook, to Twitter, and pass another hour without actually finding anything of substance, just scrolling from one site to the next.

Eventually, the story needs to go electronic. For me, this is where revision takes place. I find digital typing is great for the editing phase. I transcribe the paper page word for word into Scrivener. Then, I’ll take a look at chronology, scenes, and plot development. I love the way I can add a new text page or section, and stay organized as I work. With this, I’m able to move scenes around and bridge the story together. In “Hunger, Not Tame,” I played a lot with Kate’s past and how much to include in the story, the back-story burden. It took several revisions to refine the central scene, where her past and present collide.

But after the digital jump, I’m back to paper and pen. I print out the revised draft and I read through the story on paper. I edit, make notes, read it aloud. I mark it up. There, it develops shape and structure. Those changes are made again on the typed draft. Then, there is another printed version for a final read-through. Last minute changes are made, with pen on the paper, and corrected again on the laptop.

Handwritten work takes time. My electronically-inclined friends claim I’m doubling my time on a story. You could have been done by now. But good storytelling shouldn’t be fast or easy, no matter the method. Writing stories is, for me, a hands-on process, an artistic process of creating a world, of creating a person, of creating a story. Writing by hand allows my creative magic to have its space.