The Everyday Mind • Chad Frisk

Bretty Rawson

BY CHAD FRISK

I’d never before considered handwriting to be an art form.

For me, handwriting was always a tool. I used it to build thoughts on a page, or just to fill out forms. It was slow. It was blunt. It was annoying. That’s how I had always thought of handwriting in English, and for a long time I thought of handwriting in Japanese in the same way. That is, until I met Takemoto Sensei.

“Make sure you use an extra soft pencil,” Takemoto said.

I went to the college bookstore and bought one. Slouching in a hard wooden chair, I pressed the gray tip to the off-white page of the worksheet he had given me. I could hear his voice. "Trace the lines," he said. It came with a smile that was mildly irritating.

The work was both boring and a little bit humiliating. I had written those characters for four years as a high school student, but there I was, tracing lines like a fourth-grader. The connection was appropriate, however, because I actually spent the first week of fourth grade crying over my handwriting. Ms. Ramcke had given me back a writing assignment covered with red pen. “This isn’t fourth grade writing,” the comment read. My letters still used the kindergarten stencil, filling three lines. Ms. Ramcke wanted me to shrink them down to fourth-grade size. That night I told my mom I didn't want to go to school anymore. I was curled into a lump in the corner of my bed. She did what most parents would do. She said she was sorry and rubbed my back. But then she did something else. "Maybe Ms. Ramcke is right," she said. And before I could wipe my nose, she was poking me in the back with a notebook. "Let's practice."

*

English letters aren’t very complicated. There are twenty-six of them (a few more if you include capitals). They don’t require you to make very many strokes. You don’t even have to take your pencil off the paper most of the time.

Japanese letters aren’t like that. There are three writing systems: hiragana, katakana, and kanji. Two of them – hiragana and katakana - are relatively compact, with about 46 characters each. There are thousands of kanji characters, however. And neither hiragana, katakana, nor kanji are easy to write – at least, not if you want to write them well. In high school, I didn’t stand a chance. But in college, Takemoto gave me one.

I heard voices as I tried to control my soft pencil: "Trace the lines," Takemoto said. "Let's practice," my mom added.

I sighed and continued to trace. Slowly, something strange started to happen. As I sat there, moving the pencil from top to bottom and right to left across the page, I found myself enjoying it. I stopped to look at my handiwork.

“That’s not bad,” I thought.

I kept writing. Before long, all of my notebooks were covered with Japanese. Hiragana, katakana, progressively less misshaped kanji. I was hooked.

*

Takemoto Sensei's approach to handwriting was totally new to me. For me, handwriting had always been an annoyance; for him, it was a craft. There were ways to apply pressure to the pencil. There were proper paths to follow, angles to be aware of, particular compositions that looked better than others. I came to love writing because there were ways to do it better.

That was almost ten years ago. Since those days, I’ve occasionally exchanged the pencil for a brush. The game changes entirely. Kanji are fun to write with a pencil. Writing them with ink, however, is a trial. If you stop the brush, you will end up with blobs. If you press too softly, your lines will be weak. If you press too hard, your lines will blend into black mush. If art is about degree of difficulty, then the brush is the tool of a master.

I am not a master. In a normal calligraphy session, I write the same kanji character fifteen to twenty times before I feel satisfied. It’s hard! With a brush, every mistake compounds. One small mistake gets me thinking about what I’ll do better the next time which causes me to make another mistake which causes me to drown the rice-paper in ink.

For me, it’s about maintaining focus from the beginning of the first stroke to the end of the last one. If I do fifteen to twenty attempts, I’m usually able to maintain that level of focus one time. I used to think that there was nothing I could do about it. But now I’m not so sure. Obsessive reading in cognitive science and a semi-regular meditation routine have made me think that focus is something I can train. I thought maybe I could use kanji to do so.

So I decided to try an experiment. I chose to write one kanji compound every morning, selecting a word that I thought would put me in a constructive frame of mind for the day. Furthermore, I only gave myself one shot.

Fumei, Uncertainty

Sitting at the table, the stars still shining in a dark, winter sky, I stared at the blank piece of paper. I tried to map the coming kanji onto it. 不明. Fumei. “Uncertainty.” I looked at the brush, sitting in the black inkwell. “You only get one shot,” I thought. Then I picked up the brush and started to write.

Ideally, the lines would have flowed out of me. Ideally, the brush would have regulated itself, increasing and decreasing pressure on its own, flicking between strokes, pausing, trailing away as I held it. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened. I caught myself thinking of something else when I would have liked to be thinking of nothing but the tip of the brush. “Too bad,” I told myself, and, after scribbling some English in the margins, went to the sink to clean out the inkwell.

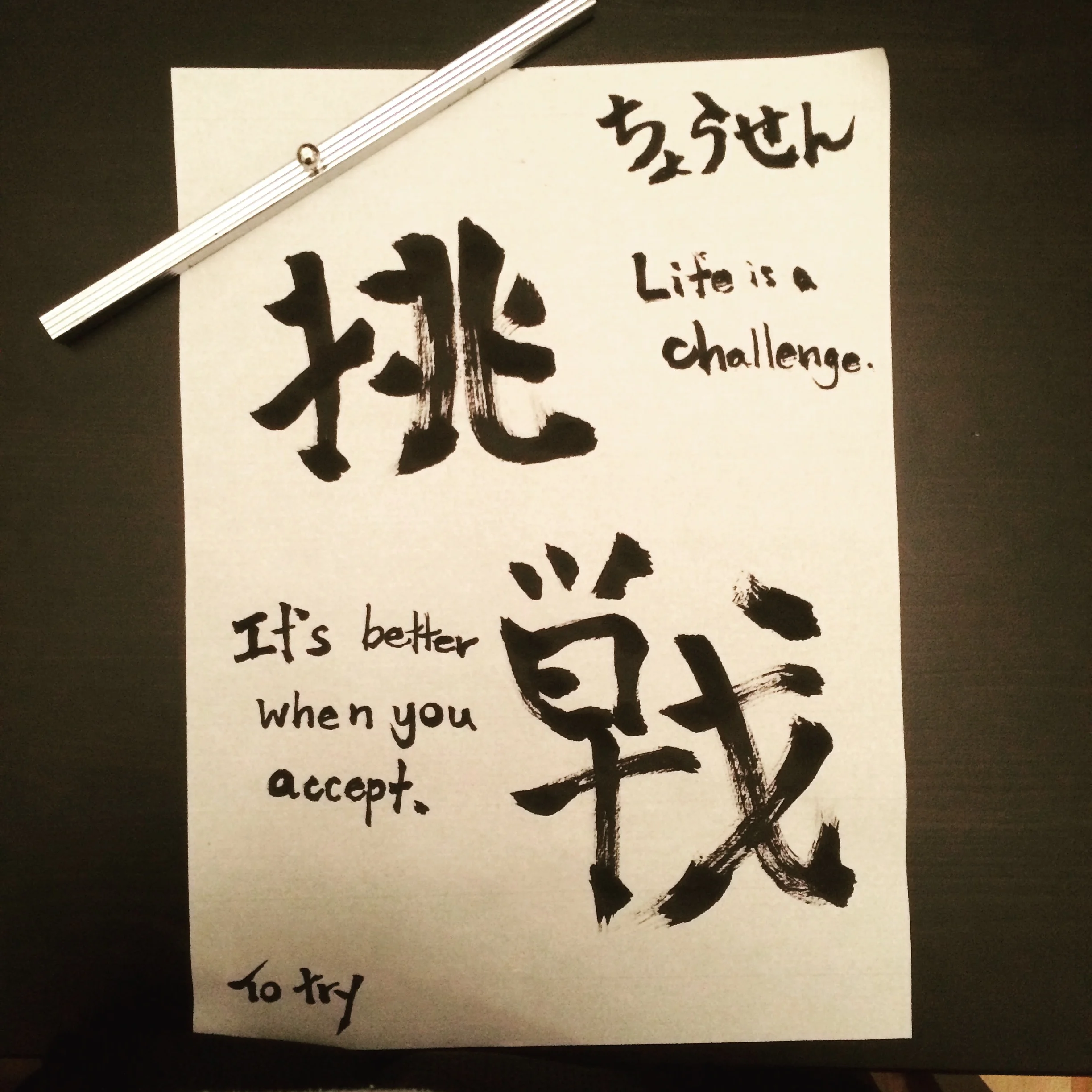

I came back the next day. “What word do I want today?” I asked myself, and waited for a response. I didn’t have to wait for long. 挑戦. Chōsen. A hard word to translate, but one that is often rendered as “to try”, or “to challenge”. I wrote it quickly, hoping that speed would equal elegance. It turned out alright.

Again, the white space at the corners of the page caught my eye. “Life is a challenge,” I felt myself writing. “It’s better when you accept.”

The word echoed in my mind throughout the morning. Chōsen. Did it make me act differently than I otherwise would have? It’s hard to say for sure. But even months later, the word still pops into my mind. I think it gives me a jolt of strength.

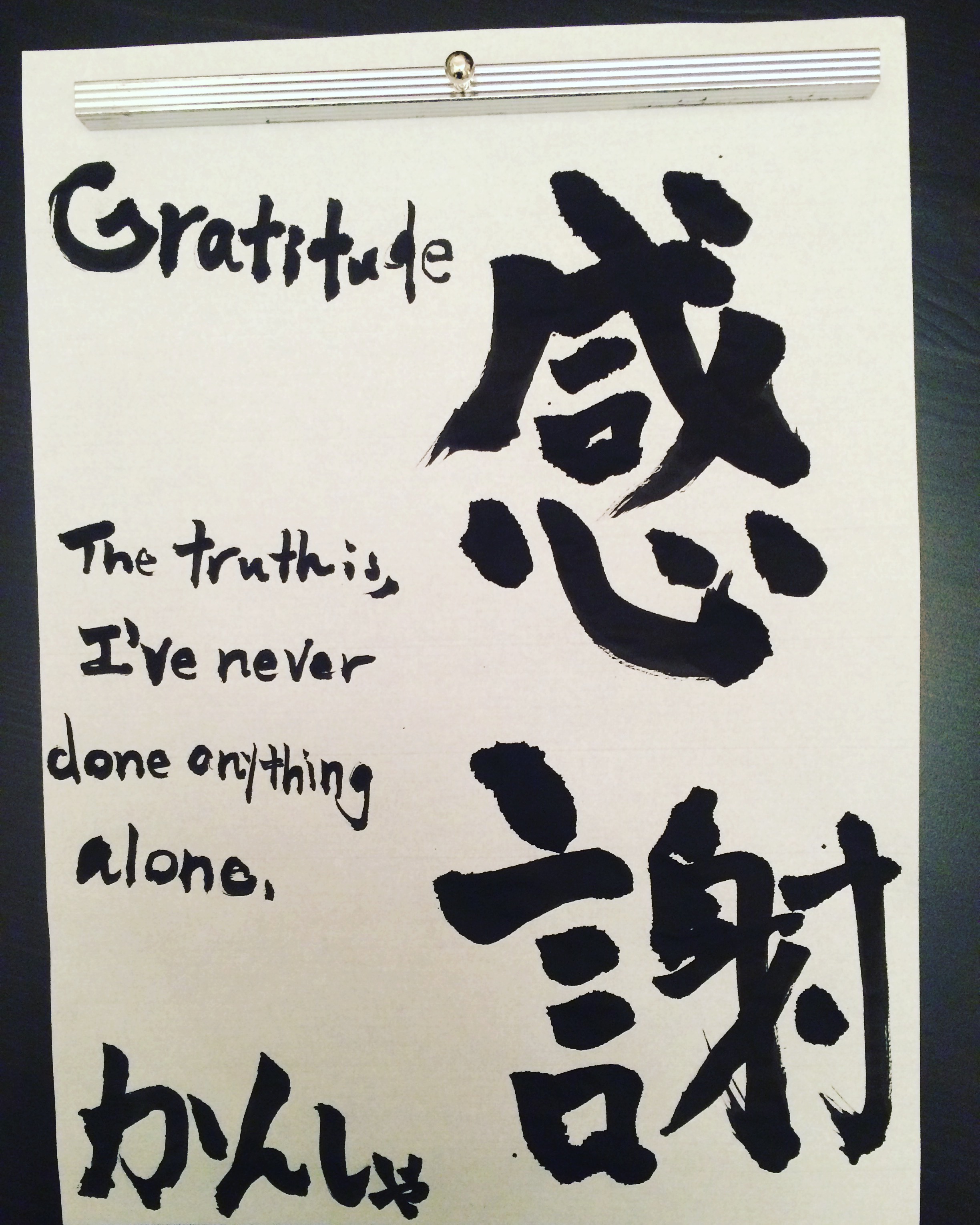

The next day I chose – again – the first thing that came to mind. Kansha. “Gratitude”. I felt a little bit nervous because I had been posting the calligraphy to Instagram. “Will people think I’m posting this just to look good?” I worried. The next thought was even more worrisome: “Am I actually posting this just to look good?”

I thought about it for a second. "Maybe not just to look good,” I reasoned. Then I paused. “But at least a little."

Then I posted it.

For three weeks, I didn’t run out of words. I found that every day I had something in my life to work on, and I was eventually able to find a word to express it. Here are some of the words that came to mind as I thought about what I wanted to bring to the day.

Nobiru. To grow. I’ve found that holding the intention to grow is enough to transform what would otherwise be the meaningless detritus of the everyday into (what at least feel like) important lessons.

Shuchu. Focus. Sometimes focus happens naturally, but usually I have to maintain it in the face of distraction. Intending to do so (and continually reaffirming that intention) is the first step.

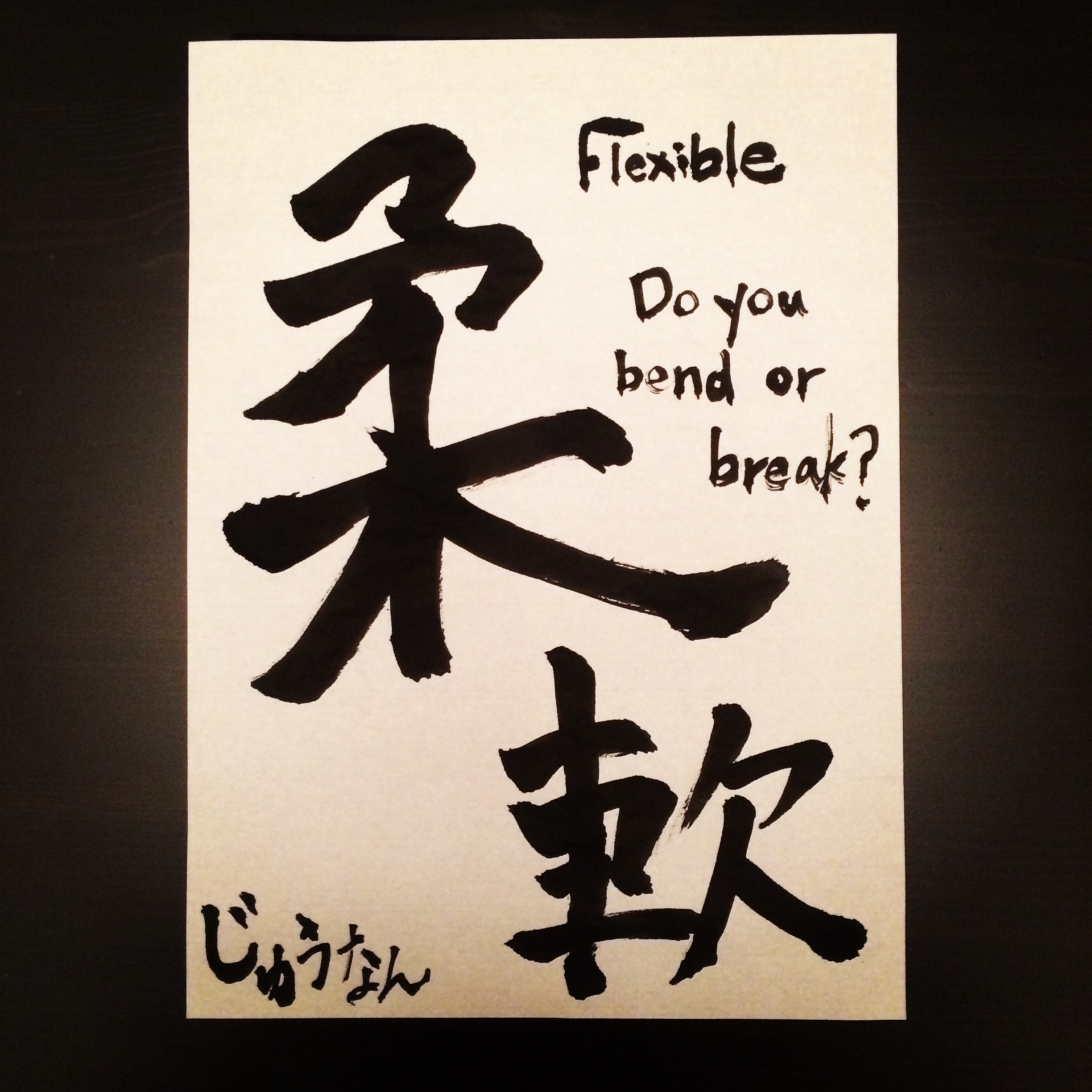

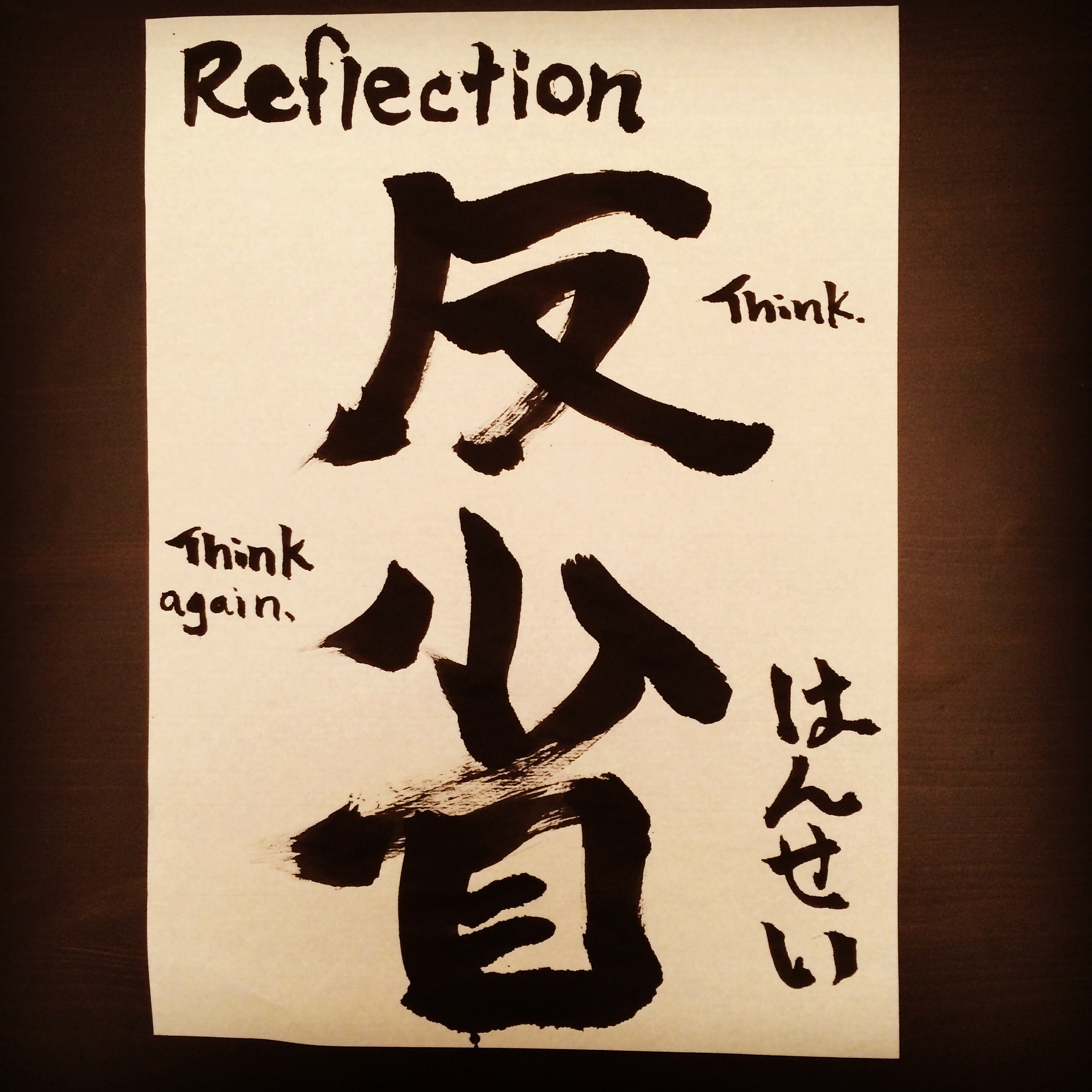

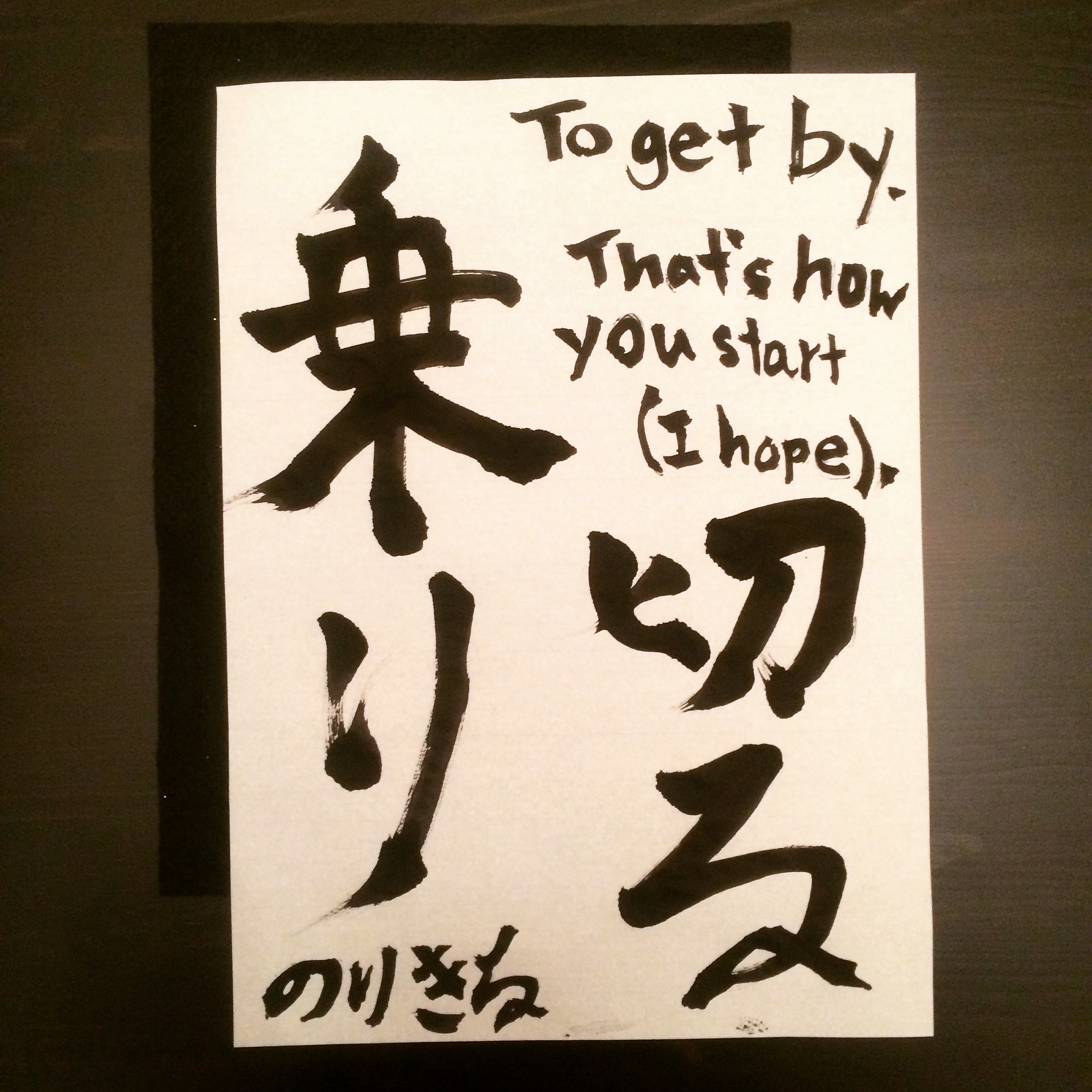

Junan: flexible. Hansei: reflection. Norikiru: to get by.

It was an interesting experiment. It lasted three weeks. It changed from a morning ritual to an evening one. It ended not because I ran out ink, but eventually, the drive. I also ran out of words. Once or twice, my first attempt was so bad that I had to allow myself a second. But more often than not I waited out the impulse.

What made one day better than another? What conditions allowed the brush take over one day, and prevented it from doing so on another? It’s hard to say. Sleep quality, maybe. My mood, definitely. To tell the truth, there were some, or maybe many, days that I really didn’t want to write anything.

“Let’s skip it today,” a voice often said. "Do you really want to take all that gear out just to write on kanji?"

“I know,” I always forced myself to reply. “It’s kind of annoying.

“But we’re doing it anyway.”

*

Handwriting has taught me that I don’t always want to do what is good for me. It started in fourth-grade. I didn't want to shrink my letters to fit in one line. My letters fit perfectly fine into three lines. But I needed to grow up; I would be in trouble today if my letters were still six-inches high. Ten years later, I didn’t want to change my Japanese handwriting either; however, if I hadn’t, I would have missed out on a chance to participate in what I now consider to be a very meaningful art form.

The lesson I took from the calligraphy experiment is the same: writing the characters took effort. I had to expend the energy to set up the equipment; I had to think of a word, either to jump-start my day or to encapsulate it; I had to submit myself to the pressure of having only one shot; and I had to live with whatever I came up with, though sometimes I failed at that.

But the effort was worth it. Takemoto gave me a seemingly remedial homework assignment that lead to a craft. In a lot of ways, life is also a craft – one that I’d like to master. Sadly, without conscious effort I tend to produce a scrawl, both in handwriting and life.

Happily, I think I know what to do about that. Now the challenge is to actually do it.