The Pen Thing • A.E. Osworth

Bretty Rawson

BY A.E. OSWORTH

The Pen Thing started with my mother. She kept a small yellow notepad in the kitchen, and she would write on it with a blue felt tip pen—the edges of it smooth and round, curving a u-shape up to the tip. It had metallic flecks in it—the barrel of the pen, not the ink. She had other colors—red, green, and black—all kept in the junk drawer, scattered around with twine, two rulers with marker all over them, and my father’s construction-strength tape measure. She made lists and wrote notes to my brother and I with these pens, always only these pens. She’d start her letter B from the bottom, way below the soft straight line when she wrote her name, Berit. The first letter almost looked like a heart.

When I sought out one of her pens, standing on my tip-toes to reach into the junk drawer, my mother would warn me: don’t grab the permanent ones. Back then, I thought it was because if you wrote on your skin with permanent marker, it would never come off. I was convinced that’s how my grandfather got his Navy tattoo. And so I used Crayola for longer than was reasonable. But now I know: she didn't want anyone else using Her Pen.

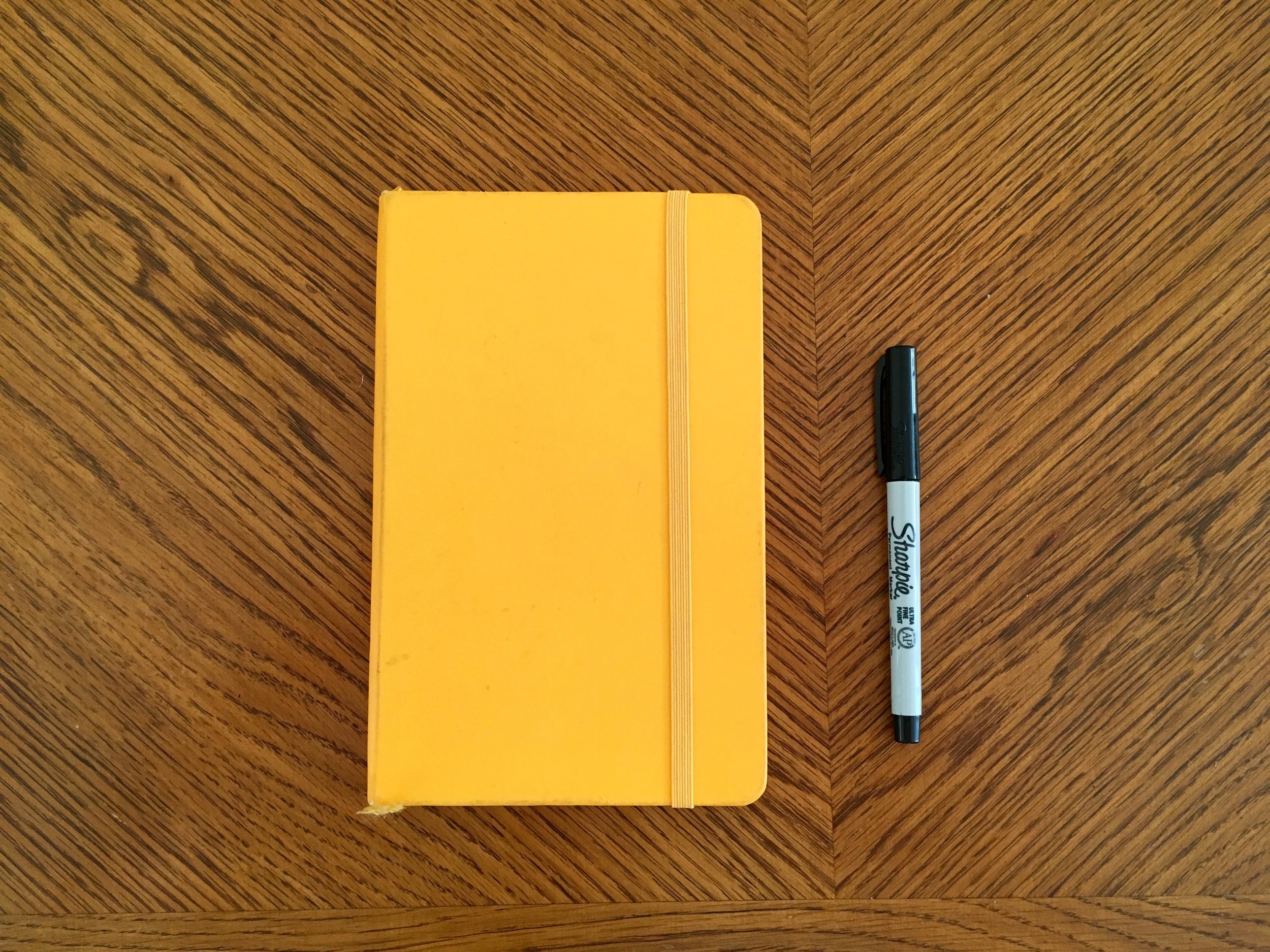

The first sign of The Pen Thing came in college when I bought a pack of three extra-fine-tipped Sharpies. After first use, I ignored every other writing utensil I possessed. I think I was looking to make an indelible mark upon the world. They resembled my mother’s pens — the felt tip ones — but differed from them just enough that I felt like I was individuating. I kept long lists of verbs I could use in my acting training — “You can’t just feel — you have to get on stage and do.” — all written in Sharpie. I wrote on my scripts in Sharpie. After college, I started keeping a journal and I wrote that in Sharpie, too. It didn’t matter that it bled to the other pages. Sharpie was the most permanent, and I feared death. Sharpie was the most consistent, and I feared change.

Someone borrowed one of My Sharpies once and wrote on the rubber sole of their sneaker with it like a heathen — the tip was no longer the sleek, immortal ink delivery service that attracted me so to the Sharpie. It was frayed. I began to carry around My Sharpies and other Sharpies — a whole box that I could give away when someone asked if I could lend them a pen. "Keep it. Don't worry about it, I have a whole box." I won't want it after you've used it, were the words I did my best to keep to myself.

The Sharpie era lasted a good long time. My journals are proof: the smudges and spidery bleeds are telltale. It was my father who broke the spell. I was in South Carolina for Christmas, about to finish a journal and start a fresh one. Oh, what a holiday! New Journal Day! I usually had at least two of My Sharpies in my backpack, the one with all the patches from Europe. I scoured it and couldn’t find either one of them, nor the backup unchristened third Sharpie, which I swore I’d left in the front pocket in the same place as emergency tampons.

On that day, my father lent me a pen. It was the one he used to write with in his Franklin Covey planner before he retired — ink black with gold fountain tip and clip, a small Pelikan pelican embossed on it if you look closely. He led me into his library and showed me how to load ink into it. “You can keep it, if you like,” he said. "I'd never steal your pen," I replied. "But I will borrow it."

I took it to the table and wrote an entry in my journal: it wrote like a dream. I filled the yellow journal and sitting nearby was a new red one, and I saw an opportunity to be a continuous person for an entire Moleskin. I walked over to my father. He was watching television with my mother. I asked him if I could steal his pen, and he laughed — he put one hand on his chest and threw his head back like he always does. He never did replace his pen. Perhaps I should feel sad and return his pen. I will not return his pen.

Fountain nibs mold to a person’s hand, you know, just like felt tips. But they are so much more permanent. When a felt tip pen comes to the end of its life, it goes in the garbage. A fountain pen is like having a pet that knows your voice and lives forever. I thought there was something special in that — that the nib on that pen had gotten used to my father and was then getting used to me. Part of me feels like I betrayed my mother in this moment — I did not steal her pens.

I wrote with my father’s pen for seven months. During that time, I lived in the attic of the house my father and grandfather built in 1954. I made it through the whole red journal with that pen. Once, I thought I lost it. I started hyperventilating and my fiancée made me check all the closets. One of our cats pushed it through a crack under a door that looked like it was made for a gnome — it lead to the eaves. When I retrieved it from the dust and the cotton candy insulation, I remember crying a little. But I can’t find the journal entry to prove it.

That’s when I decided that not losing the pen was more important than being a continuous person. So I bought a ballpoint seven-year pen from the bookstore on the corner. It’s called a seven-year pen because it’s supposed to have enough ink to write meters and meters per day for seven years. That’s a lot of years for me to get attached to a pen! But ballpoint — what am I, a madwoman? I chose the one with a bicycle on the clip because I aspire to be a better person than I currently am, transportation- and fitness-wise. I took it with me on a trip to the Grand Canyon and Joshua Tree National Park; research for a novel I imagine I will resurrect someday. I wrote fast, drunk with ballpoint power, on the edge of a desert staring into the great bowl of the sky.

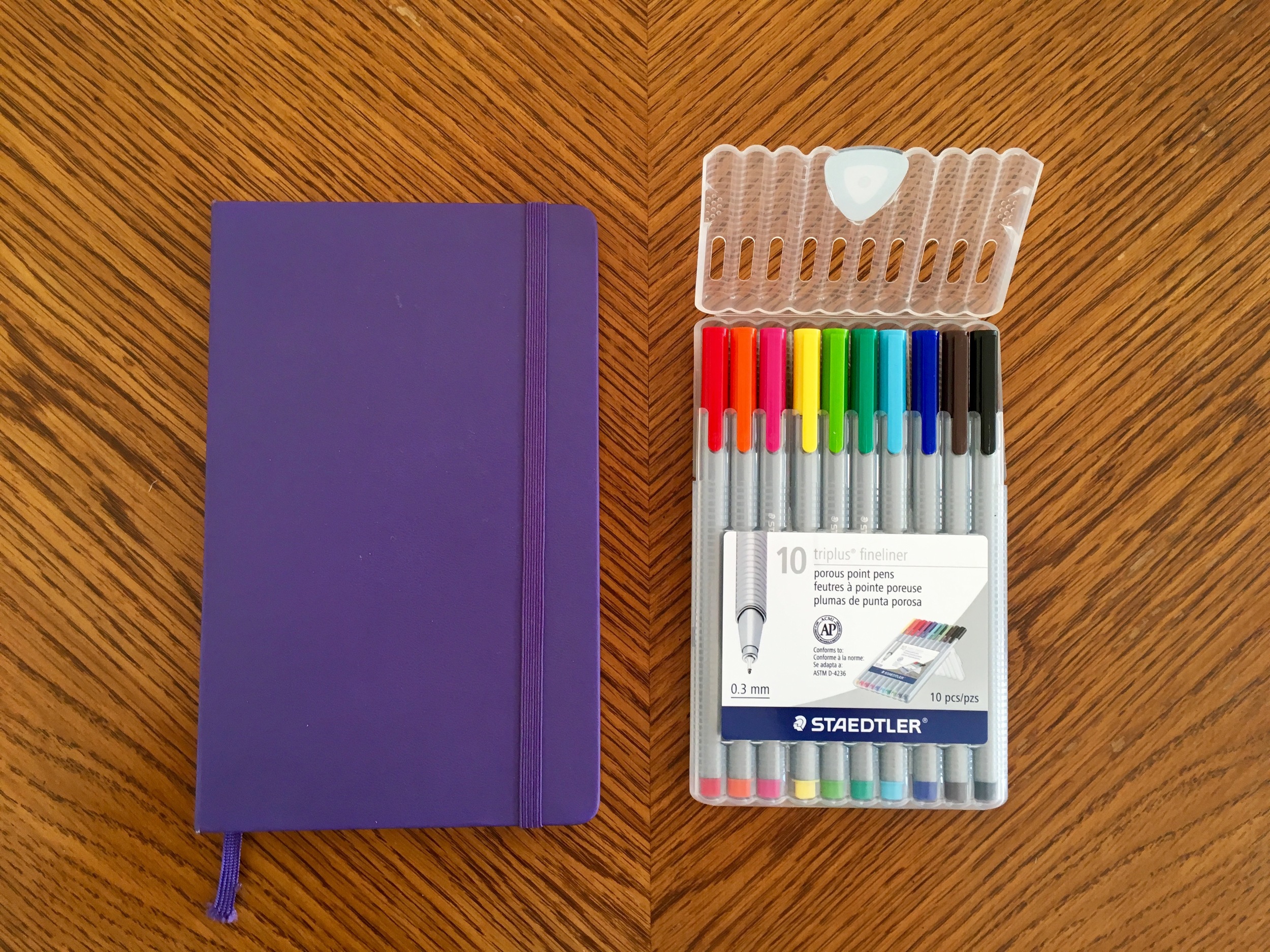

It broke recently, that pen. I could sense it happening. The clip came loose and I knew it would crack. It still writes, but it is no longer My Pen. Other people can use it now, if they want to use a broken, imperfect, mortal pen. Sensing it was about to break, I bought a set of Staedtlers triplus fineliners. There are ten of them, each a different color, and I tote them around in the clear case they came in. They’re called “porous point pens.” That means “felt tip pens,” in pen addict speak. My friend asked to borrow one recently, and I looked her in the face and said, “No.” Even though there are ten of them, they are all Mine — the “porous tips” have now bonded with me and I’m keeping them. She has since purchased her own set.

I tried to use the pens evenly so they wore out at the same rate. My journal, the one I just finished, is a veritable rainbow inside. And the clear, easel-prop storage case began to break. I devised a plan that consists of attractive Washi tape and ignoring the death of things.

Since beginning my latest journal, I am using only the black pen in the Staedtler set. It may seem like I’ve thrown caution to the wind, pentropy be damned. But no — it’s because I can get a million more black fineliners. When these pens break and break my heart, the black one, at least, can be replaced. The barrel is a metallic silver; it is triangular, but the corners are round. Smooth. That I am marching ever toward being my mother is not lost on me. Sometimes I write with the fountain pen in the safety of my own apartment, when I need to channel my father. My need to individuate is gone. I could do with a bit of permanence, a bit of history. I could stand to write with the pens and the preoccupations that got used to my family’s hands.