The First Two Words That Popped Into My Head Were Industrial Sadness

Bretty Rawson

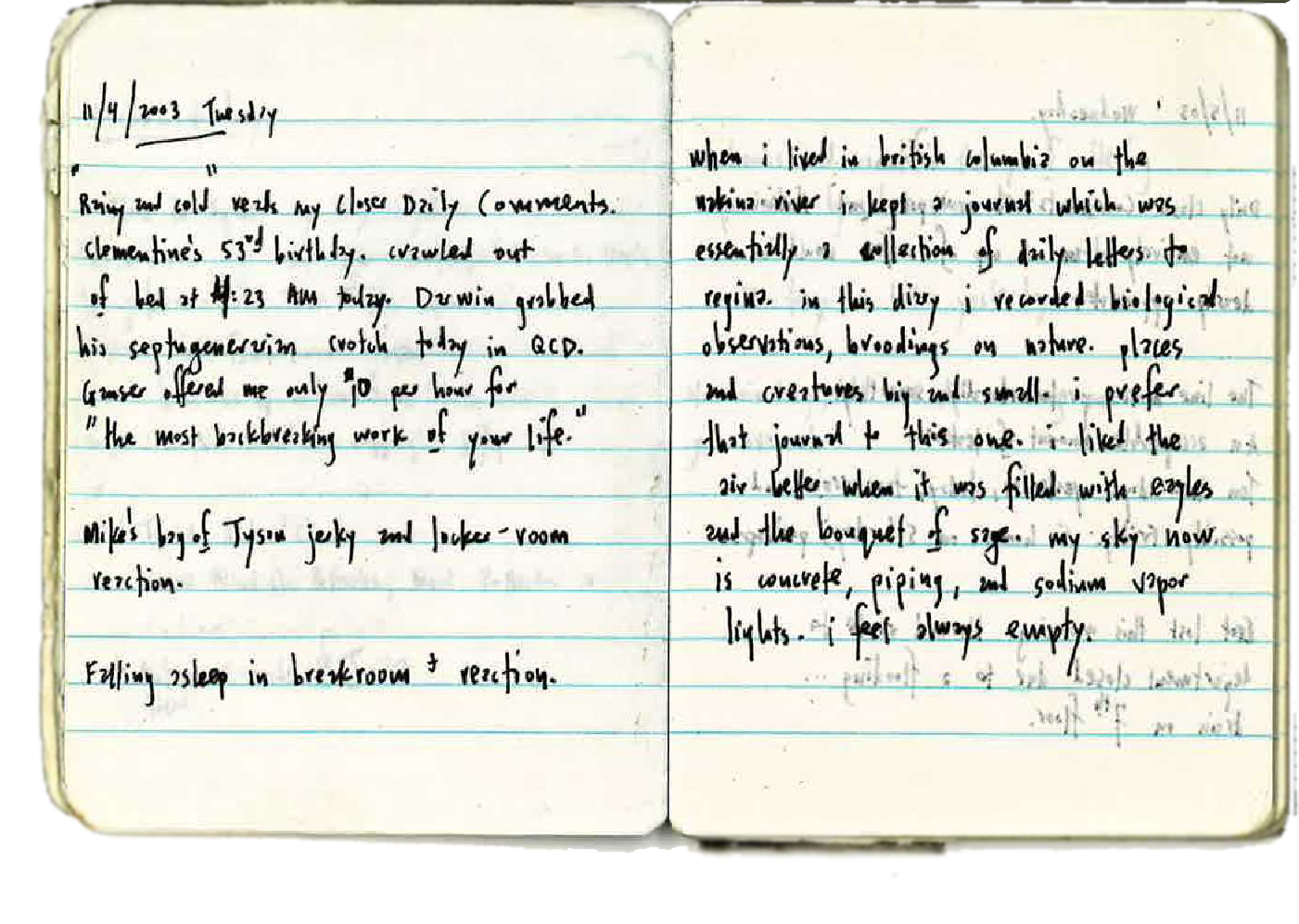

"when i lived in british columbia on the bakina river, i kept a journal which was essentially a collection of daily letters to regina. in this diary, i recorded biological observations, broodings on nature."

HANDWRITTEN: In one entry, you wrote about the time you spent living in British Columbia. “I feel so empty," you wrote about working at Oscar Mayer. You described the notebooks you kept in British Columbia as "biological observations." If you were to boil the meat diaries down into two words, what would they be?

BUTLER: The first two words that popped into my head were “Industrial Sadness.” You know — and it’s so weird — where I was living in British Columbia, two months before taking this job, it was up close to the Alaskan border, about as wild as it gets on this planet. I caught salmon out of the river with my bare hands, we saw several grizzly bears every day. It was unbelievable. When I came back to civilization, I had a really hard time. I guess it’s called culture shock.

I would sometimes break down in grocery stores. I had a really hard time with fluorescent lighting and all the array of food choices. That was really staggering for me. I was homesick for that — and not just British Columbia — but that kind of wild, you know? Night sky, clean air, birds. When I say “sadness,” that was a big part of it. I was like, God, I graduated from college, I graduated with honors. What am I doing here? Why can’t I be back there? I would get to the plant at four in the morning and be done by one or two in the afternoon, and I would be so tired I would take a nap. It felt like my days were cooking by really fast, you know? It was a sad time.

"That's what kind of day it was. Even Satan mocks us."

HANDWRITTEN: What did a typical day look like? Was there even a typical day?

BUTLER: Initially when I started the job, I would get up at three in the morning, eat breakfast, and make coffee. I didn’t have a long commute to work. It was only like 10 or 15 blocks away. I would sit in the parking lot in my truck for a while and just stare at the building, which at that hour, it was wrapped in fog because it was billowing steam, and with all these lights, it was very imposing.

I would walk in, go to the locker room, put on my plastic booties to cover my boots, put on a white smock, my hairnet and helmet, and I would walk up two or three floors to get to the place where I worked. We had an office meeting with our supervisor, who would tell us what kind of meat we were working with that day — ham and cheese loaf, salami, or something like that — and then he would give you your work assignment.

“Butler, you’re running this machine," he would say.

The work pretty much never changed. It was this meat or that meat. Sometimes my daily assignment would change, or somebody would get sick or have the day off, so rather than running this huge press machine that sealed all the lunch meat, maybe I was working as a stripper, which was not stripping off your clothes, but these plastic casings off giant tubes of lunch meat. So yeah, each day was pretty much the same.

HANDWRITTEN: What were the other tasks you or others did?

BUTLER: I’m going to try and remember this now. One of the jobs was stripper. Basically, the lunch meat comes to you on a giant rack that’s sort of like a pallet. It’s stacked from your feet to your head in six rows of 40-pound tubes of frozen meat, and they’re wrapped in blue cellophane. So all day long, all you do is pull a 40-pound tube of meat, put it on a table, take a sharp knife, run it across the plastic, pull the plastic off, and then you hand this giant stick of meat to the slicer.

The slicer ran the machine that slices the meat. So his job — and I’m going to say "his" sometimes because some of these jobs were truly kind of separated by sex or gender based on danger, weight lifting, and stuff like that — but the slicer would put this giant stick of meat up into a machine and then slice it out into these stacks of meat that you would buy at the grocery store.

The next place it goes to is — and I can’t remember their title — but they were packagers. They take the stacks of meat off of conveyer belts, and put them into these plastic bubble Oscar Mayer packaging. Then, I think it came to the sealer. I had that job quite a bit. I ran this giant heated press, and I would take the packaging and put it into the press machine, which would seal it, and then I would send it down a conveyer belt where it was cut into individual packs — initially it came on a tray of eight or something — and then it went to the boxers. And sometimes I was a boxer, too, and at that point, the packaging had come in fully-trimmed and you’re putting it in boxes and setting it on a pallet.

There were weird things sometimes. You’d be taken from one department to another, shot over to another department to do some totally different job for a day or two. But that was out of the ordinary.