You Consume Anonymously And I Am You

Bretty Rawson

HANDWRITTEN: You had an interesting poem toward the end of the first notebook. “You consume anonymously and I am you,” you wrote. It speaks to consumerism, but also the absent hand. That entry is undated. In fact, the last thirty of this diary are dateless.

BUTLER: What had happened was we would break down for these periods of time — for an hour, forty-five minutes, half-hour, whatever it was. You’d just be sitting on this cold assembly line. There wasn’t much to do. You’d clean up your work area and then you’d still be hanging around. And a lot of people would use that time to chit-chat, but sometimes, especially if I was running the closing machine — the press — I was isolated on the assembly line and I had a lot of time to think. The notebooks just became an outlet for that.

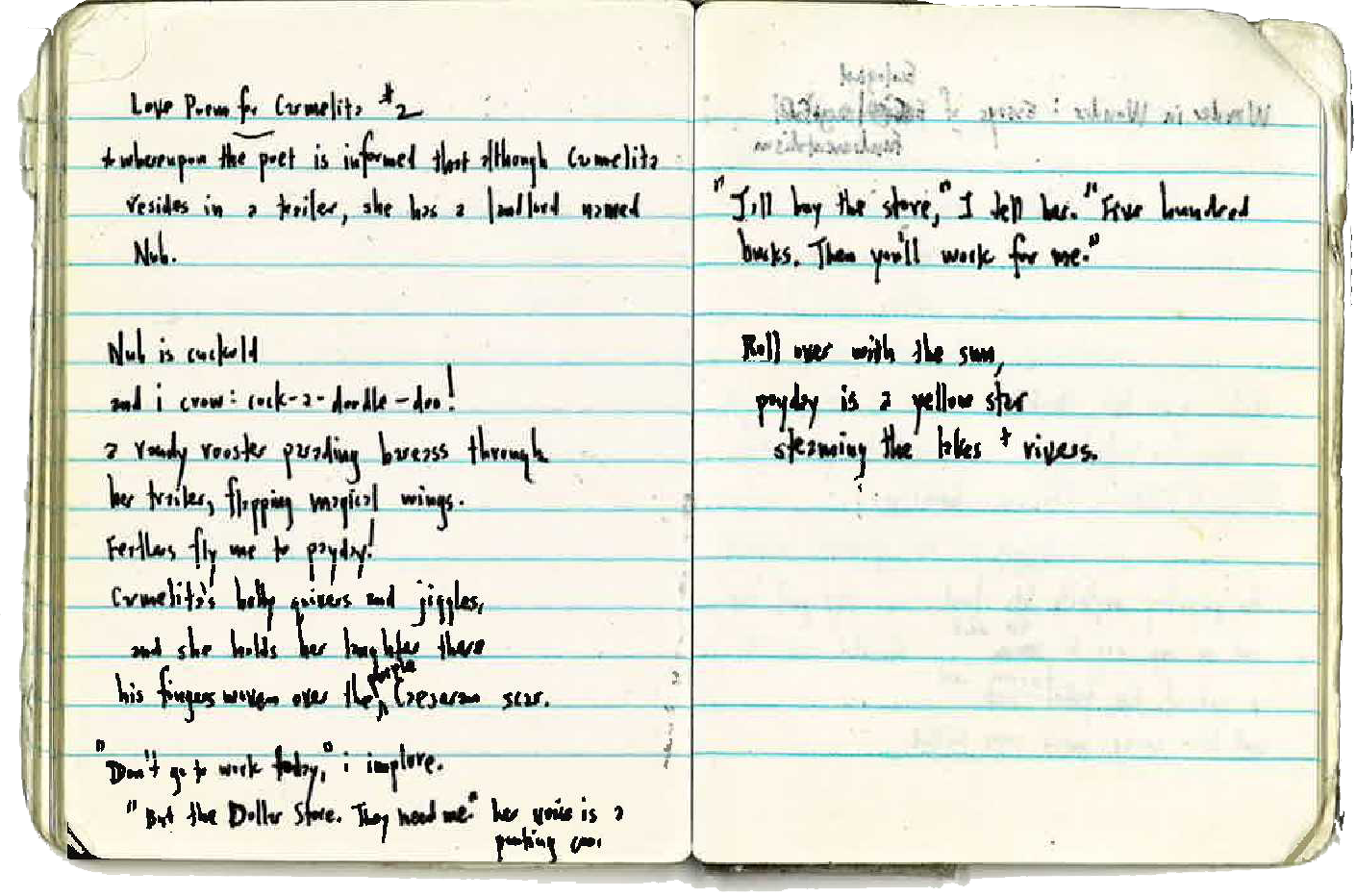

It’s been crazy going through these notebooks and seeing these early ideas that became something else. There was actually an idea for a poem that ended up getting published by the Progressive Magazine after I was done with this job. It’s dated November 3, 2003. The title of whatever I wrote there, I can’t even read my own handwriting.

The story was basically: I was about to walk into the plant in the morning. You’d walk through this long parking lot and then you’d get to a guard shop before you could enter the plant. You’d have to scan your badge or something like that, I can’t remember. And there were a couple newspaper stands and I walked by that morning, November 3rd, and on the Chicago Tribune headline, it said “US Copter Hit, 16 Die,” and I remember looking at that and taking it in and thinking about the people that had died in the helicopter that day and they were probably about my age. The next day, I don’t think the newspaper had changed — I don’t think the newsboy had come to take the newspaper — so the next day it was the same headline, and the day after that. So for three or four days, I’m looking at the same Chicago Tribune headline about these soldiers that had died and I ended up writing a poem about it and sending it to "The Progressive" and that was kind of my first big break in writing.

Matthew Rothschild printed it and paid me $150 and I was in an issue of "The Progressive" with Howard Zinn and Barbara Ehrenreich, and I could tell my mom, "Hey, go to Barnes and Noble and you can find my writing in this magazine." It's just been really crazy looking through this thing and seeing that my ideas haven’t really changed, for better or worse. My fascinations are still the same.

HANDWRITTEN: In some entries, you write these little notes for the future, it seems. Like a little positional anchor cue, should you want to recall a memory. For example, one in the beginning was: “So and so is watching after taking a nap in the lunch room.”

BUTLER: By the time I was taking the journal, reality was pinching. Who knows how long I was going to work there. I do remember scary moments where I think I fell asleep in a break room and one of my union representatives found me there. He wasn’t mean but he was stern. He just said, "If you get caught doing that, you’re going to be fired and there’s nothing we can do to help you." I shouldn't have been taking a nap in there. I mean, I didn’t prolong my break or anything like that, but I remember feeling like it was sad enough to be working there, but to be fired would’ve been sad and embarrassing, too.

I took pride in the fact that I was working hard. My wife and I were just dating then but we shared an apartment, so I was bringing home a paycheck and I was a part of the household, but to have been fired from Oscar Mayer for doing something stupid would have been hard to tell her and my parents. There was an uncomfortable feeling that I was better than this job, but also, I was not better than this job. That kind of dynamic was always sorting through me. And what happens if you get fired from that job? You’re clearly not better, you know? You couldn’t handle it.

"i was positive i would be fired."

It’s weird also seeing those reminders. And also, going through these notebooks and remembering that people got badly injured here and there. Recording when my body didn’t feel right. I noticed in one place when I started feeling carpal tunnel in my wrist. The scary thing is when you’re new at that job, before six months are over, you’re just on a probationary level. You couldn’t really complain if you were having health problems because they would just let you go. So there were definitely weeks, maybe months, where I was suffering bad carpal tunnel. Like, I couldn’t pick up, say a baseball bat or golf club. I couldn’t clinch my hand.

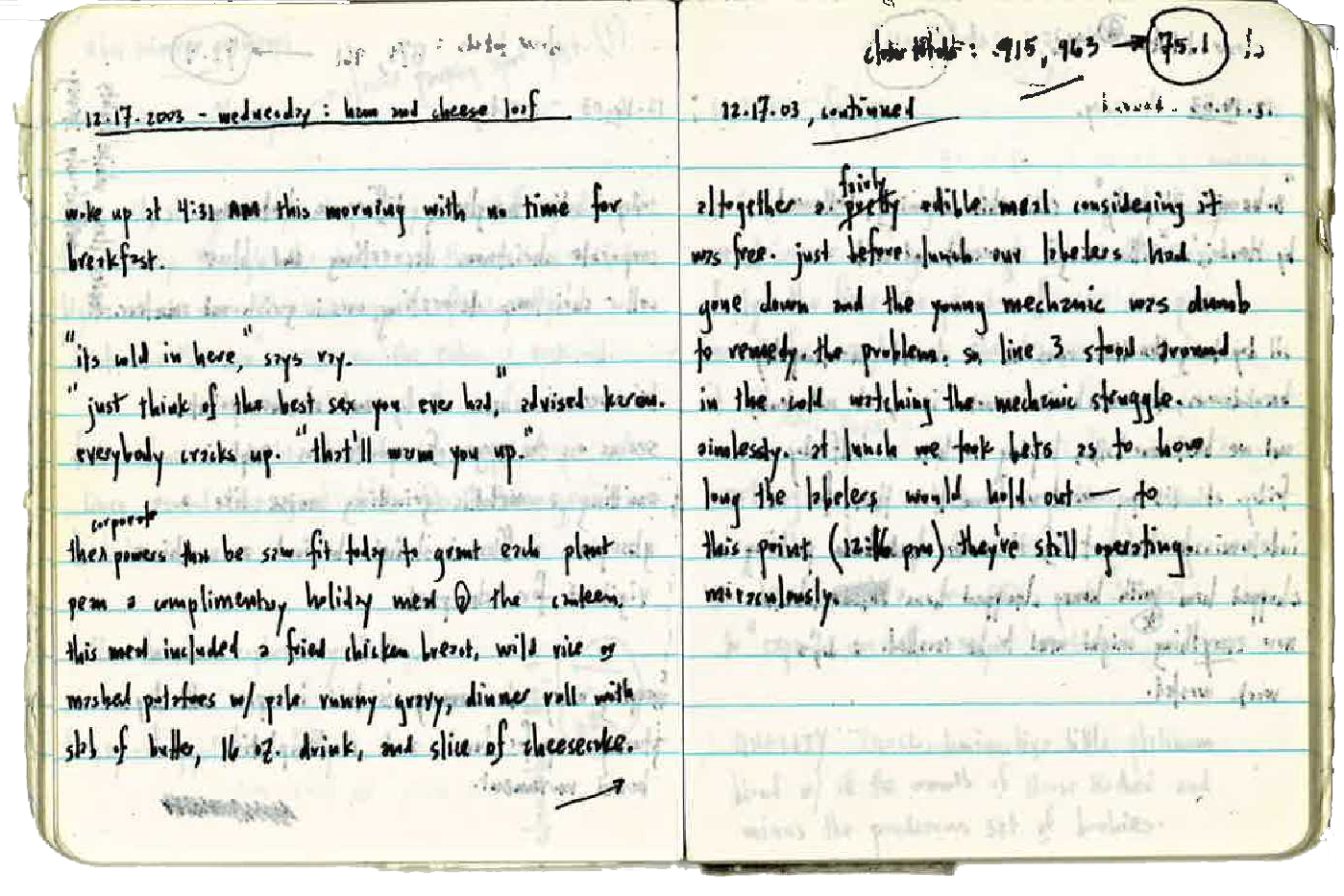

It was very cold in the meat-packing plants. Somewhere between 25 and 40 degrees, like a wet cold. So for several weeks I just felt very sick. I couldn’t get the cold out of my bones. I couldn’t warm up. You also couldn’t quit, you know? You just had to keep going until you got those six months. So writing down some of those health things, it’s been interesting going over that. I think in some ways I was recording the danger in working there, too. I was always afraid someone was going to get hurt, and I was going to be witness to something like that.

HANDWRITTEN: How ephemeral was a place like that for people? Were they working there for years or did people pass like clouds?

BUTLER: There’s no easy way to answer that question because it’s all over the place. They would be constantly hiring. When I got hired, I was part of a group of twenty people, Brett. I remember very clearly on the first day, we all got — see, you’re going through a corporate training which is happening in a corporate training room inside the plant, it doesn’t look scary or anything like that.

But then you’d go get your gear and on your first real day you’re really walking into the innards of this old meat-packing plant and it smells like meat spices and it smells like blood and sometimes there was blood on the ground. That was really, really shocking. I remember on the first day, somebody on my training group went to the assembly line with all of us and then there was a break and that person didn’t come back. They just walked out on the first day. And over the first six months, a lot of the people that I came in with just left. They didn’t come to work. That said, I knew people in my department that worked there ten, fifteen, twenty years. And there were stories of people who worked there for fifty years.

I remember one classic story about a 90-year old guy, who worked in the basement of the plant and had been there 60 years or something like that. The story was that he was illiterate, he had never had to read, he just knew how to run these machines in the basement, so there was a weird folklore about the plant. You didn’t know what was real or not, but it seemed possible that there could be this guy living in the basement and had been forever.

"slicer greg tells us an anecdote of his weekend in QCD. 'you ever have one of those moments at a restaurant where some brat ruins your time by being entirely belligerent?'"

"'so i look over at the kid and indeed, his little hands are buried in his pants.'"