Resolution #2: Stop Dating Men with Mediocre Ambition • Kaitlin Kominski

Bretty Rawson

If you haven't made any resolutions this year, here are four great places to start. May your resolutions be short, sweet, and sharp.

Read MoreSince we aren't on every social media site, let us come to you. Enter your email below and we'll send you our monthly handwritten newsletter. It will be written during the hours of moonrise, and include featured posts, wild tangents, and rowdy stick figures.

Keep the beautiful pen busy.

Brooklyn, NY

USA

Handwritten is a place and space for pen and paper. We showcase things in handwriting, but also on handwriting. And so, you'll see dated letters and distant postcards alongside recent studies and typed stories.

search for me

If you haven't made any resolutions this year, here are four great places to start. May your resolutions be short, sweet, and sharp.

Read More

Portrait of Gail Anderson, by Paul Davis

BY SARAH MADGES

With decades of teaching, typography, and creative collaboration under her belt, New York-based designer and writer Gail Anderson has a CV worth calling home about — at least, it earned her the holy grail of graphic design achievements, the AIGA medal, in 2008. The design-ecstatic aesthete made her first layout years before her tenure as art director at Rolling Stone, literally cutting and pasting a magazine mockup of the Jackson Five in her childhood bedroom.

She’s been busy ever since, developing identity campaigns for Broadway shows, co-writing typography books with Steven Heller, teaching type fundamentals in the MFA program at SVA, and co-partnering with Joe Newton at their eponymous Anderson Newton Design firm for projects ranging from book jackets to outdoor installations. Despite the ease and efficiency of digital design technology, Anderson swears by taking time to untether from the laptop, insisting that craft is crucial to typography, and slowing down with a pencil and piece of paper is crucial to honing that craft. In November we reviewed her latest book, Outside the Box, which honors this DIY by-hand approach, following the hand-lettering trend from its individual, artful beginnings to its contemporary commercial ubiquity.

I had the chance to talk to her about the book’s composition, as well as handwriting and hand-lettering in general — how it plays into her life as a designer, and design as a whole.

Childhood Sketchpad

Design inspiration from childhood, 1974

SARAH MADGES: What role does the pen and notebook play in your life?

GAIL ANDERSON: I’ve grown increasingly particular about the pens and notebooks I use, since I really enjoy the physical act of writing. I’m a fan of black Pilot Varsity fountain pens and Pilot Precise V7s. And I was extremely loyal to those Japanese Oh Boy notebooks with the thick, ruled paper, even after Chronicle acquired them and put the Oh Boy logo on the front. I have two left that I’m saving for God knows what since they’re now out of production. I moved on to Muji, and then Moleskine, and am now working my way through some Field Notes steno pads. I even keep a paper date book, so clearly the art of writing still means a lot — possibly way too much — to me.

MADGES: You divided your book into four sections — DIY, art, craft, and artisanal. How did you come up with these four categories? Was it always clear you were going to organize the book this way?

ANDERSON: I knew I wanted to have some kind of system to categorize the material. I’ve learned a lot from working with Steve Heller for so many years, so I did what we always do with our books — I spread the work out with someone I trust and we let it sort of organize itself. It’s too confining to categorize stuff in the research stage, but you can’t wait till the design stage either. It was really fun to come up with section titles, and once my design partner, Joe Newton, and I got through that process, I felt like we had the contents of a real book in front of us.

Type Spread from Outside the Box.

MADGES: Do you see a significant difference between what’s considered handwriting and hand-lettering? How would you define the difference — is it intent? Actual artistic design and effort?

ANDERSON: I wrote out Debbie Millman’s foreword by hand and consider that to be handwriting rather than hand-lettering. When I look at it now, though, it seems so deliberate (and some folks have assumed it was a font). Maybe it does have something to do with intent — I’m not quite sure where the line in the sand is.

Broadway theater poster designed at SpotCo

MADGES: Why do you think people respond to hand-drawn lettering? Do you think there will always be a demand for it? Do you imagine it will lose popularity any time soon?

ANDERSON: People connect to branding and advertising that feels intimate and artisanal. It’s somehow less “corporate," even though hand-drawn type is used by just about everyone now. I think Andrew Gibbs from the Dieline said it best in the book’s intro: “In all my years of seeing packaging trends come and go, there is one style that has stood the ultimate test of time: hand-drawn.” I admit that a few years ago, I thought, “Well, how long will this last before we swing all the way back to Helvetica?” But in some form or another, hand-drawn type is here to stay.

Type Directors Club letterpress post card

MADGES: Do you see a similar resurgence in classic or vintage fonts in reaction to the digital age?

ANDERSON: I see students who crave the opportunity to work with their hands — kids who’ve pretty much grown up in front of a computer. While embracing technology is key to their success as designers, they don’t want to feel tied to their laptops. We did a hand-lettering class last week and the students actually started applauding at the end — that’s how hungry they are. And I think they are beginning to seek out classic and vintage fonts, which is such a relief after so many years of all those awful free fonts.

MADGES: Is there a distinct moment or brand that signaled the beginning of the hand-drawn movement’s resurgence? Or was this a gradual, inevitable change in response to an increase in digital and technological saturation?

ANDERSON: I wasn’t plugged in enough to recognize a particular moment, but it certainly seemed like everyone started drawing — and posting — around the same time. I think it’s all about Pinterest and the other sites and blogs where designers started strutting their stuff publicly. It sometimes felt like everyone jumped on the bandwagon without adding a new twist, but the best of the best have carved out their own niches. And yes, I do believe that it was a reaction to technological saturation and the desire to create something seemingly personal and unique.

Jackson Five scrapbook, 1972

MADGES: What first compelled you to typographic design? When did you first start collecting typefaces and fonts?

ANDERSON: I started designing magazine layouts as a child, first for The Jackson Five, and then for The Partridge Family. Even then, my pages were filled with my 12-year old version of typography, which was based on Spec and 16 magazines and their Letraset rub-down type. I started saving photostats of typefaces in college, but things really clicked when I worked at Rolling Stone with Fred Woodward. His good taste and sharp eye were instrumental to the growth of my own skills.

MADGES: Marketing research has found that the first piece of mail someone is likely to open has a handwritten address. Do you think this is because of handwriting’s scarcity that it’s perceived as more valuable? Is it more authentic? Personal?

ANDERSON: I’m not in a hurry to open anything that’s got a bulk rate stamp or a mailing label (I hate them on greeting cards). But I’ll give something that has a handwritten address on it a chance, though admittedly I’ve been fooled once or twice by handwriting fonts. I appreciate the idea of someone taking a few minutes to put pen to paper.

Hand-drawn lettering from a cross-stitch book that continues to inspire Anderson

Outside the Box: Hand-Drawn Packaging from Around the World

MADGES: You note in your book that hand-drawn lettering isn’t necessarily popular just because of the attendant sense of nostalgia, but rather because of its established historic design technique. What makes this technique more or less difficult to execute? What are the pros and cons?

ANDERSON: Drawing naive type is one thing—and often not as easy as it looks—but doing what Martin Schmetzer, for example, does just blows me away. There’s a tremendous degree of patience and utter stillness required, but there’s also a touch of genius that is at a whole other level. When I was editing through book images, there were times when I’d just stop in my tracks to stare at pencil sketches that were so incredible that they might as well have been finished pieces. And Martin thought his sketches were “rough”—seriously.

MADGES: I’m similarly amazed that a brand as huge as Chipotle uses handlettering. Do you think it is feasible for any even larger companies to follow that approach? How do you think consumers would respond if McDonalds rebranded with letterpress?

ANDERSON: The idea of a McDonald's “artisan” chicken sandwich rings about as true as the idea of a company like that rebranding with letterpress. But Chipotle’s pretty huge and their incredibly inviting branding brought in a lot of customers, including me. Hatch Show Print does McDonald’s! Ha.

New “Make it Here” SVA poster

MADGES: What does it mean for design and typography that the next generation might not be able to read cursive because it is no longer taught in schools?

ANDERSON: I guess we’ll see a lot more child-like lettering that isn’t an affectation! I see my nieces’ and nephews’ handwriting and it’s just terrifying. But I am a product of Catholic schools in the 1970s, where penmanship was paramount. On the other hand, I also see young designers who can make letterforms into magic on their computers, so perhaps it all evens out. As long as there are cursive typefaces to buy, they’ll just have to learn to read script even if they can’t write it.

MADGES: Looking at your site, I’m impressed that you are an incredibly versatile and prolific designer. You’ve worked as Art Director at Rolling Stone, an educator at SVA, are on the board of TDC, you designed probably my favorite US Postal stamp — the Emancipation Proclamation. How do you take on these projects — what strings them together? And what’s next?

ANDERSON: I actually just started a new job recently that should keep me challenged for a good long time. I’m now the Director of Design and Digital Media at Visual Arts Press (SVA). My career is tied to a love of working with words, whether it’s designing them or writing them. The Emancipation Proclamation stamp may be my all-time favorite project. I got to design using a piece of history — the first words from the document itself, and was able to set the actual type at Hatch and watch Jim Sherraden print the poster that was then reduced to stamp size. It doesn’t get better than that.

HAND-DONE BY ABBY TROTT

Warpo Man, as this misshapen stick-hero is called, was the result of a bored teenager (me) and an old school 90’s version of Microsoft Paint. He was designed to be a character who is as warped in personality as he is physically; Warpo Man unapologetically (and often unfortunately) speaks his mind without filter.

After being forgotten for a number of years, Warpo Man resurfaced in my college notes. He served as a sort of visual outlet to enhance lectures and help me focus, but would often end up taking over my notes entirely.

I moved to Japan after graduating, and my parents ensured that I didn’t forget about Warpo Man by sending me photos of my childhood drawings. I hung them to remind me of his two biggest fans. Warpo Man has made appearances in books, birthday cards, and various gifts over the years. “One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish Me!” was specially edited for me dear ole muddah this year.

To find and follow Abby's performative appearances, you can find her on Instragram and twitter at @abbyleetrott.

Handwritten is wildly happy to announce its newest curator, Carly Butler, who will be heading up a new column called Life's Letters.

The column comes from a discovery, which turned into journey, blog, and premise for a book: 110 love letters written from her grandmother to her grandfather after a chance meeting during World War II. The trajectory of her life took an irreversible turn: she followed the letters and her heart to London, England, to retrace the steps of her grandmother's letters 67 years later.

At the outset, she didn't intend to write a book, but while in London, she realized something: she was writing her own Life's Letter with each step. So at the conclusion of the physical journey through this past, Carly set out to put down her experience, which has turned into the forthcoming memoir, Life's Letter.

Along the way, something else happened unexpectedly: as people began to find out about her journey through articles, interviews on television, and more, people started sharing their own life's letters with Carly, each as unique and moving. She started receiving requests from universities, organizations, and genealogy clubs to speak on behalf of the power of the pen, which only sent her in further examination of the connective tissue of the physical traces of a past and person. It shined a bright light on a simple truth: every family has a story. But what we don't realize without zooming out, is that so many of these stories are preserved in pen. And so, this is what her column with Handwritten will be about: the stories told through letters about life, lives, and living.

The first post will be on Sunday, January 17th, which aligns with time: the first letter of her grandma's is dated January 17th, 1947. It will also be the first time Carly has published a single, entire letter of her grandmother's. In this column, her own life's letter will provide the base for others, and create a space to collect and recollect unforgettable lives through letters.

We welcome Cary Butler to the Handwritten team, and cannot wait to watch her column unfold.

To tell Carly your story, and submit to her column, you can reach her at: lifesletter@gmail.com.

Carly Butler currently lives in British Columbia, Canada with her husband Adam. She is a photographer and writer by passion, and a customer relations coordinator at a bank by profession. She has a degree from the University of Guelph in International Development and Economics. Her story has been featured in media outlets such as BBC Breakfast, The Times, London's Evening Standard, BuzzFeed, Huffington Post, Today Show, Good Morning America, the Global News, and dozens of other publications.

BY DEMETRI RAFTOPOULOS

Graham Barnhart is from Titusville, Pennsylvania, the birthplace of the oil industry. He is an 18D, Special Forces medical sergeant, and has been deployed twice: once in Iraq for nine months, and the other for seven months in Afghanistan. I didn’t know all this when I met him at Hotel El Greco in Thessaloniki. All I knew was that Graham Barnhart was a poet and my roommate for the summer. We were the only two men taking part in Writing Workshops in Greece on the island of Thassos. It being my first time living away from home and having a roommate other than my parents, there were a lot of question marks in my eyes.

The day we were to meet, I went for a long walk along the port to the White Tower and other landmarks drenched in Greek history. In between monuments, I wondered if Graham and I were searching for the same thing; if we would be capable of having a good time with a beer in one hand and a pen in the other; and if we could mix the sentimental with the comical, the work and the play. A few hours later when I returned to our hotel and skipped up the flights of stairs, I was stopped by an unfamiliar, familiar face. I wasn’t sure what Graham looked like—his Facebook profile picture was a black and white image of a random old bearded fisherman—but something told me this was him.

“You’re Graham,” I said, almost accusatory.

“That’s me,” he replied.

I would learn this to be his normal, quiet, calm exterior. I would also learn that he wildly records his surroundings, almost instantly rendering them into lines of expression. One of our first nights, we sat in the restaurant beneath our rooms, watching locals throw napkins over the others dancing to the live music. When Graham asked why they did this, I told him it was a sign of respect, to the musicians and to the dancers. During the first student reading, Graham read a poem about his time in the military and in Greece that centered around the image of the napkins.. He had this uncanny ability to live in the moment, to inhale all that was around him and let it all sink onto a page, and a poem, as he exhaled.

Throughout our time together, I learned something else about Graham — he handwrites wherever he goes. This makes sense, as he is always on the move in the military, but I wondered how he balances the two worlds — the military and literary. We caught up recently and talked about this: his time overseas, balancing the military world and the literary world, and his thoughts on the handwritten word.

DEMETRI RAFTOPOULOS: In Thassos, you carried around your notebook everywhere, especially on our excursions to other towns. What kinds of things were you writing?

GRAHAM BARNHART: I write down a mixture of notes and poems, usually more notes and lines than full ideas for a piece. I try to pursue an idea as far as I can in that first jotting, to get everything out as it occurs to me. I try not to list off ideas for what the poem will be about. That feels like a shying away from the sometimes (often) daunting moment of inspiration. That moment when you can feel but not yet articulate all the potential of the idea that has struck you. It’s too easy to try to categorize or outline that idea than put it aside. That avoids all the hard work and limits the creative potential to what you already understand or can conceive of.

The best work is work you don’t understand fully until you’ve written it. It’s better for me to have the image or handful of lines so that I can come back to them, hopefully experiencing again whatever it was that made me want to write them in the first place. A good idea or plan for a poem can sometimes turn into a trap.

RAFTOPOULOS: Yeah, I don’t think I ever fully follow through with an “idea” the way I thought I would when it first hits me. Always lands on the page differently than it does in my head. What’s your process like?

BARNHART: I tend to start by hand though I don’t usually think of my handwritten work as a first draft until it hits a computer. On paper I might complete a poem but keep marking it up, fussing with it really, until I get motivated enough to actually type it up. That’s when I know I have a draft rising up out of all the daily notes and scribbles that I really want to pursue.

Handwritten work feels more in-progress to me, like I haven’t quite found the right configuration of ideas and images to call it a poem. Once those components are present I do most of the finer tuning on a screen. That’s when I start thinking about outlining or diagraming the piece and when I add notes for further revision. The handwritten phase is not always a requirement, but it serves as a permanent record and a well of all the ideas and lines that might otherwise be forgotten. I love to flip through my current and older notebooks as a way to warm up to writing. I don’t always ending up working on the piece I sat down to revise but something usually happens. That’s all I can ask for sometimes.

RAFTOPOULOS: Absolutely. Do you always use the same notebook, or do you have different ones for different purposes?

BARNHART: I’ve always kept some sort of a notebook, though kept might mean that it sat in my room or desk for weeks without being used. I have a bad habit of writing down ideas in whatever paper is handy rather than using my designated writing notebooks. So I end up with notes and drafts scattered through everything else.

Having a pen and paper handy is a big deal in the military. There is always information being put out, whether it’s the time of the next formation, how many rounds of ammunition you’re drawing for the range, or a casualty description for a medevac request. It’s considered unprofessional to show up for a briefing or class without something to write with and on. That comes in handy when trying to take poetry notes. No one really questions what I’m doing. Not that writing poetry would be a problem, but explaining my writing to a soldier would be about as long and complicated a conversation as explaining what I do in the military to a civilian. It’s just easier most days for everyone to think I’m noting the effect range of a 60mm mortar.

RAFTOPOULOS: And one notebook specifically that you described to me as a “writeintherain” notebook.

BARNHART: Yes. Recently — the last 15 years maybe — little flipbooks kept in zip lock bags have been replaced with waterproof notebooks made by a company called “Rite in the Rain.” They have thick, waxy pages and only work with regular, old ballpoint pens, rather than the fine tip pilot pens I really like. In fact the notebooks even come with an “all weather pen” which is just a short, steel ballpoint.

RAFTOPOULOS: How about your handwriting — does it change from notebook to notebook? I imagine writing in the rain could “weather” your penmanship.

BARNHART: I don’t make the handwriting look different on purpose, but because of the materials used it just does. It actually feels harder to write on the all weather paper, kind of like the notebook is resisting anything not specifically military. Though of course it’s also a pain to write military stuff. That material tends to be short notes and lists rather than lines and stanzas.

I mentioned not being very good at keeping my writing consolidated. So on top of half filled moleskins lying around I also have a bunch of waterproof notebooks filled with operation orders, mortar targeting grids and the occasional poetry stanza. I don’t try to keep these things separate in the notebooks though. I like the juxtaposition.

RAFTOPOULOS: You have experience teaching and I know you want to teach in the future. Do you think you’ll assign writing prompts in class, just so your students are forced to write by hand as you sometimes are?

BARNHART: I think in class writing prompts are fantastic, especially when they’re handwritten. That format forces a sense of urgency but also of care. You have to physically create each letter, but you may only have 5 minutes, or 10. For me this frees me from my normal analytical and self-editing process. I just get something out there that follows whatever external guidelines the prompt demands. Some people don’t like prompts feeling they stifle their own creative process. I rather think that prompts free your creative process from you, if you are diligent and faithful to the restrictions. So in short, yes, I will absolutely assign handwritten prompts.

RAFTOPOULOS: How did you decide on pursuing an MFA?

BARNHART: I decided on the MFA in undergrad and actually started the application process before I decided to enlist. It seemed like the best way to pursue a writing career and avoid student loans for as long as possible. I knew I wanted to write and didn't much care what sort of real life job I ended up with so an MFA seemed like the right way to go.

RAFTOPOULOS: What was it like writing or attempting to write in places like Iraq and Afghanistan?

BARNHART: I wrote very little digitally during deployments. In fact I didn’t write much at all. I took sporadic handwritten notes when an image caught my attention, sometimes even a full poem but I didn’t spend much time actually working. I regret that now of course, I wish I had at least kept better daily logs.

On both trips I did have my own room with a desk, a bed and some books. I wouldn’t take my laptop out on patrols or missions of course but it was around. I always had a notebook in my pocket though. Actually it was in a pouch on my body armor. I kept pen and paper, some caffeine pills and a little iPod shuffle that was plugged into my ballistic hearing protection. The pouch was intended to hold shotgun shells so it had little elastic loops sewn all over the inside.

RAFTOPOULOS: How were you able to balance both of these worlds — military and literary?

BARNHART: Most days if I ended up with some notes or lines, I felt like that was a success. It was a sufficient sign that I hadn’t given up or lost writing which was a big concern for me post undergrad. I went from learning to write in an environment structured to support that to one structured to support a very different goal. I was also learning and studying in the military, but of course none of it was directly poetry related. It helped to think of it, especially the miserable stuff, as material.

RAFTOPOULOS: Were you ever worried that you would stop writing completely?

BARNHART: There was a point during the medical training when I actually thought I would. That course was intensive. We did physical training from 6:30-8:00, and then we were in class from 9:00-5:00. Afterwards, we spent three to four hours studying. There were written and practical tests every week. Learning that much medicine that fast pushed everything else out of my head. I completely forgot all of the Arabic I had spent the last six month learning. I didn’t feel like I had the capacity for any other kind of thinking.

RAFTOPOULOS: I can imagine. I’m happy you haven’t stopped writing. How much of your poetry is inspired by your time overseas?

BARNHART: Much of my writing is loosely inspired by my deployments, mainly Afghanistan because it was more combat-oriented and also more recent. Many of my poems are set there, though I prefer to rely on an ambiguity that implies the setting alludes to it. I think of the war and my military time in general as a useful context for exploring ideas in poetry but I don’t think many of them as “about” the war, or at least, the ones I find more interesting to write are not.

Then again, my time in the military is relatively short compared to most of the guys I worked with. Some of them have been to Afghanistan more than ten times, though some of those trips were as contractors. I’m hesitant to talk about what the war is like because I only know about my brief experience, leaving out the long history of this conflict, not to mention that largely silent or unheard voices of the people who actually live there. I never want to say this is what Afghanistan is like. I can only say this is what I saw in Afghanistan while I was there as an American soldier.

Graham Barnhart is an 18D, Special Forces medical sergeant, and is an MFA in Creative Writing candidate at The Ohio State University. His writing has appeared in the Beloit Poetry Journal, the Sycamore Review where he was a finalist for their 2014 Wabash prize, Subtropics, The Gettysburg Review, and Sewanee Review. He is also a finalist for the Indiana Review's poetry prize and the Iowa Review's Jeff Scharlett Memorial award for veterans. And is hoping to be back in Greece next summer so Demetri can continue drinking tsipouro with him and translating Greek for him.

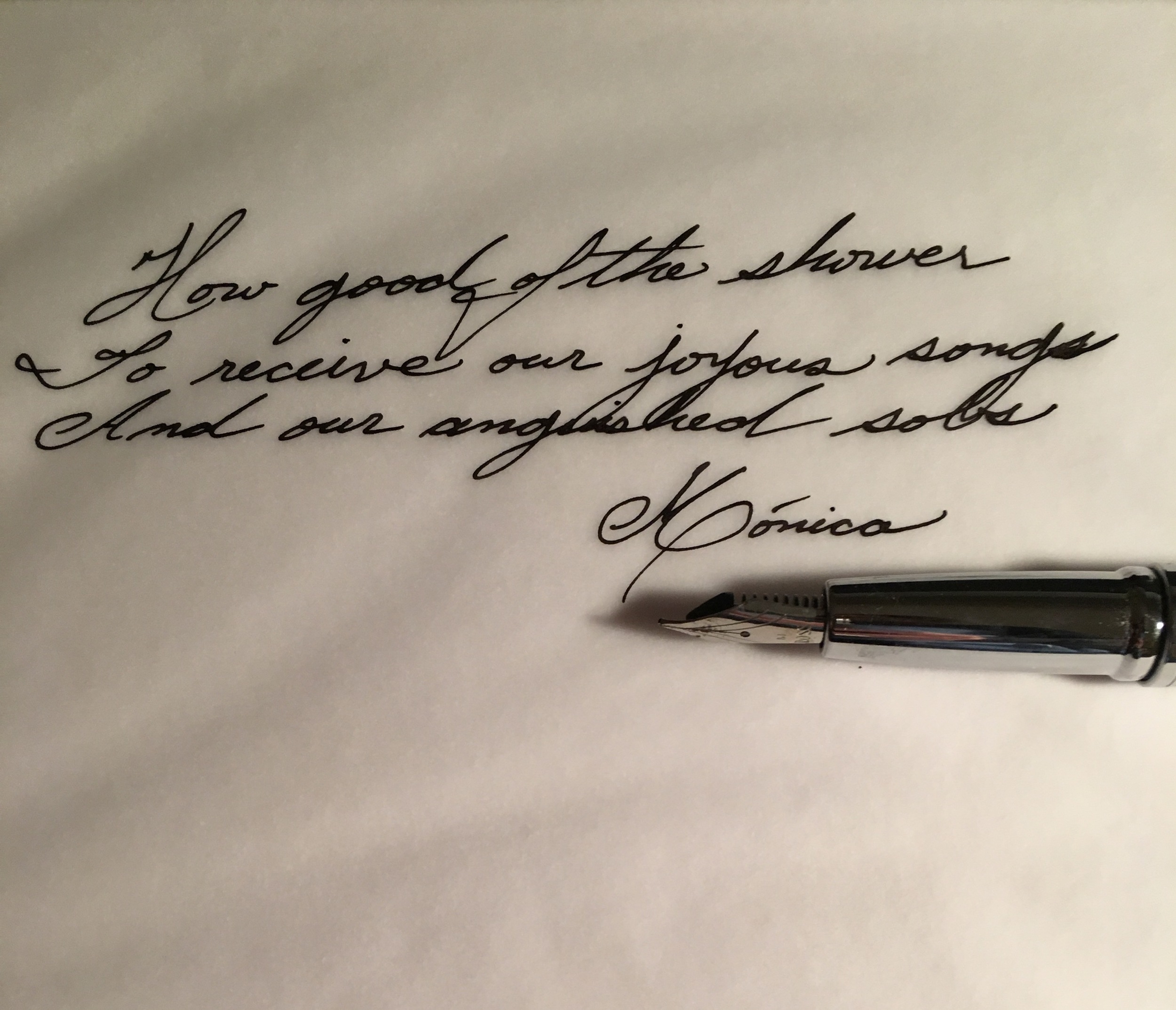

BY MONICA COUGHLIN

In school I learned to write cursive with a fountain pen and I have loved them ever since. I have had many pens, some expensive ones, but none is the workhorse that the Sheaffer Schoolhouse fountain pen has been for me. The ink always flows, it is the Sheaffer or the Cross fountain pen that I turn to the most. For me there is an intimate quality to the handwritten word. I like to write my own words in longhand, but also the words of others'. It merges their work with my writing hand and creates for me a special bond.

HAND-DRAWN BY KATY HARTMAN

We see the winter as the season of the handmade: with the holidays, the end of a year, and familiarity gathering from afar, it is the perfect environment for a little handwritten love. We asked calligraphist Katy Hartman to design four different phrases that, to her, represented the coming and passage of the feeling and atmosphere, which you will see above and below.

In the spirit of the great exchanges, if you have, received, or creates items rooted in the handwritten word, from holiday cards to new year's resolutions, send them to us at info@handwrittenwork.com. Tell us about your time, traditions, and handwritten holidays.

BY MICKIE MEINHARDT

“So what do your tattoos mean?”

I get this a lot. Anyone with ink does. People love to ascribe meaning to tattoos; as if to say that to make such a decision, to put permanent markings on your skin, has to have gravitas. But often it does not. Some even seem offended when I answer that, well, most of them don’t “mean” anything. The anchor on my left bicep? Just really wanted one. The mermaid on my right? A beautiful work of art from an artist I admire. It’s a lot like buying a painting, except instead of hanging it on a wall, it’s on my body. Forever.

But some do have symbolism. Like the smattering of line drawing on my wrists: the Deathly Hallows, an octagon for my math-teacher grandma, and wave for my beach hometown dappling my wrists. Of these small but significant ones, there are two I’m particularly fond of, both hand-drawn by me: A heart on my upper right thigh, and the words “NO TIME” on the inside of my right ring finger. Both represent the culminations of periods of extreme personal, emotional, and mental turmoil, and have become symbolic mantras to a better self. In the absence of religion — I’ve been agnostic since I learned what the term meant, though hold beliefs in various universal phenomena that one could, I suppose, call spiritual — they and the feelings they represent have become like small visible prayers to myself, without which I would certainly have been OK, but perhaps not so quickly.

The heart was my first tattoo. I got it in tandem with the small bicycle on my ribs, never seen, the summer before my senior year of college, to celebrate the end of what was and remains one of the worst period of my life.

I was living in the Bronx, commuting nearly an hour to Manhattan to intern at a fashion news website for no money and waitress after at a midtown beer bar for barely-decent money; days frequently began at 8am and ended around 2am with maybe $150 bucks in my pocket, if I was lucky. After rent and bills, there wasn’t much left over, and I was often unable to feed myself anything other than cheap college staples — bananas, beans, booze — or whatever I could scrounge from the restaurant. My apartment life was in turmoil; one of my roommates was experiencing a terrible, life-altering personal situation that, for no fault of hers, oozed into everyone’s life around her and caused a rift in our friendship. Home was not a safe or happy place for me when I very much needed it to be.

That summer, I was in the throes of battling my way out of years-long eating disorders. Three years of on-and-off anorexia and bulimia had caused deep personal revulsion and body image issues. And at that point, whatever reasons the disorders began and were perpetuated were long gone. I felt terrible all the time. Constantly tired, sore, sick of looking at myself in bathroom mirrors with hatred-filled, watery eyes. I was repulsed by what I was doing to myself. So, as low a point this was for me — over-worked, under-paid, stressed, and feeling completely alone — there was a twisted silver lining: Under the pressure of those months, I finally cracked. I resented myself for what I was doing to my body, and my mind, so much that I vowed to kick it all for good.

In hindsight, I wish I had told someone, anyone. But admitting how incredibly fucked up I was to another person was impossible, unfathomable, at the time. It would mean admitting what a serious problem I had. I was embarrassed. I didn’t want anyone watching me when I ate, looking for signs of deep-seated issues. So I told no one. I was isolated, depressed, and a mess. I drank a lot to forget my anxieties, or try to quiet them. If school hadn’t started when it did, giving me a distraction and getting me out of my own head, I probably would have lost it. Years later, a doctor would ask me, incredulous, how I managed to get over the disorders without therapy or serious treatment.

In truth, it would be years more before the aftershocks of those psychological earthquakes would finally die down, but at the time I was determined to quell the actions of the disorders as best I could on my own. I remember this decisive moment of “You will learn to get better” mostly because of an unconsciously-drawn doodle. It was on the late train ride home after a long shift at the bar. As a writer, I was always scribbling, even when bone-tired. With one of the black pens I always carried, I drew a tiny heart on my right inner thigh just below the hem of my denim miniskirt. I stared at it for a bit, willing myself to love my body more.

“This would make a good tattoo,” I thought.

A week before classes began, I took a few days to visit my hometown, Ocean City, Maryland, for beach relaxation and decompression. On the last day, I accompanied my brother to get a tattoo and decided I would, too.

I sketched the heart over and over in my journal. I’d doodled absentminded hearts into margins my whole life, but this wasn’t a college-ruled notebook. It was important that it was imperfect; not symmetrical, not too clean. I drew quickly, rapidly, trying to conjure “the one” with literal stokes of brilliance. Some came out longer, swoopy, with a flick to the point. Some were plump and short, like Sweetheart candies. The ideal was something in the middle: Curvy and cute but not comically plump.

It finally materialized, and I triumphantly circled the nickel-sized symbol and handed the notebook to the tattoo artist to scan. I sat down on the padded chair, jean shorts hiked and leg splayed, and watched. I remember how the ink welled up and sank into my skin, how I did not bleed, how surprised I was at easily enduring the pain, having always been afraid of needles. When it was over, I had a permanent reminder to be a better person to myself that would be seen, as I once told a friend, every time I sat down to pee. This was important — as any recovered disordered eater knows, the bathroom is where your indiscretions manifest. So several times a day, there it was: Love me. Love yourself. Love.

I can’t pretend it was an instant elixir, but it helped a lot. When I became an avid yoga practitioner, it took on a new form.

“Look how strong you are! You’re amazing! I love you!” It seemed to say, as it warrior-ed and stretched and danced through the poses. I came to think of it as a friend who never leaves, and always has the same good advice.

The second meaningful tattoo is relatively recent, inked impromptu on my 25th birthday this past summer, though I’d been contemplating it for some time. I swore I’d never get a words tattoo — I felt out-of-context quotes were cliché, and I’d seen some bad ones — but finding my own handmade mantras changed my mind.

As a creative, self-doubt is a constant companion. Internal body image issues aside, I've always been a confident, outgoing, and capable person, especially in my work as a writer. And, fortunately, depression has never been a clinical or recurring battle for me, like it is for many creatives. But your early twenties are a tumultuous time, and in them the melancholy demon can creep and make itself at home, often to paralyzing effect.

In the later part of 2014, I went through a messy breakup. It felt easy to actually do at the time, to say “we’re done” and walk away, but there were devastating aftereffects in the following months. The relatively short relationship was my first legitimate one as an adult, and, unprepared for the feelings that follow after you lose a love, its dissolution rocked me in unexpected ways. A lot of my body dysmorphia issues came rearing back, and while I was long past the actual disorders themselves, my image of myself was shattered. The breakup had also occurred right before Thanksgiving, meaning I had to trudge through the holidays as if they weren’t making me feel worse about being alone. And finally, I was in the terrible purgatory of waiting to hear back from graduate schools, having finished applications to various MFA programs at the end of the year. I had nothing to do except wait, wait to get better, wait to be accepted—and nothing good comes from an idle mind. Not usually one to wallow, I found myself unwilling to leave my apartment, pathetically curling up in bed with a laptop most nights, or getting wine-drunk and watching the ceiling fan while listening to sad girl music. I knew I was not OK. I saw it, and didn’t like it. But even then, I wasn’t sure how to fix myself. A go-getter who rarely sat still, I’d never been in this situation before. I’d never felt so deflated, like my will to be a person had leaked out of my pores and evaporated. There was a lot of denial, a lot of “I’m fine,” until my roommate finally sat me down and said, “No, you’re not.”

It took a while. But by spring, I’d eased out of the hole. I got into my top school, took on new projects, and started to feel like myself again, in part from the cheesy recitation of several mantras. Say what you will about “quotes” (I did), but they can help more than expected.

One is a poem, “The Laughing Heart” by Charles Bukowski, which begins: “Your life is your life. Don’t let it be clubbed into dank submission.” I printed it and hung on my bedroom wall, and on moments when the gray cloud loomed I would remind myself: This is your life, and it is bright and full and amazing, if you let it be. It ends “You are marvelous. The Gods wait to delight in you.” That is true. For everyone.

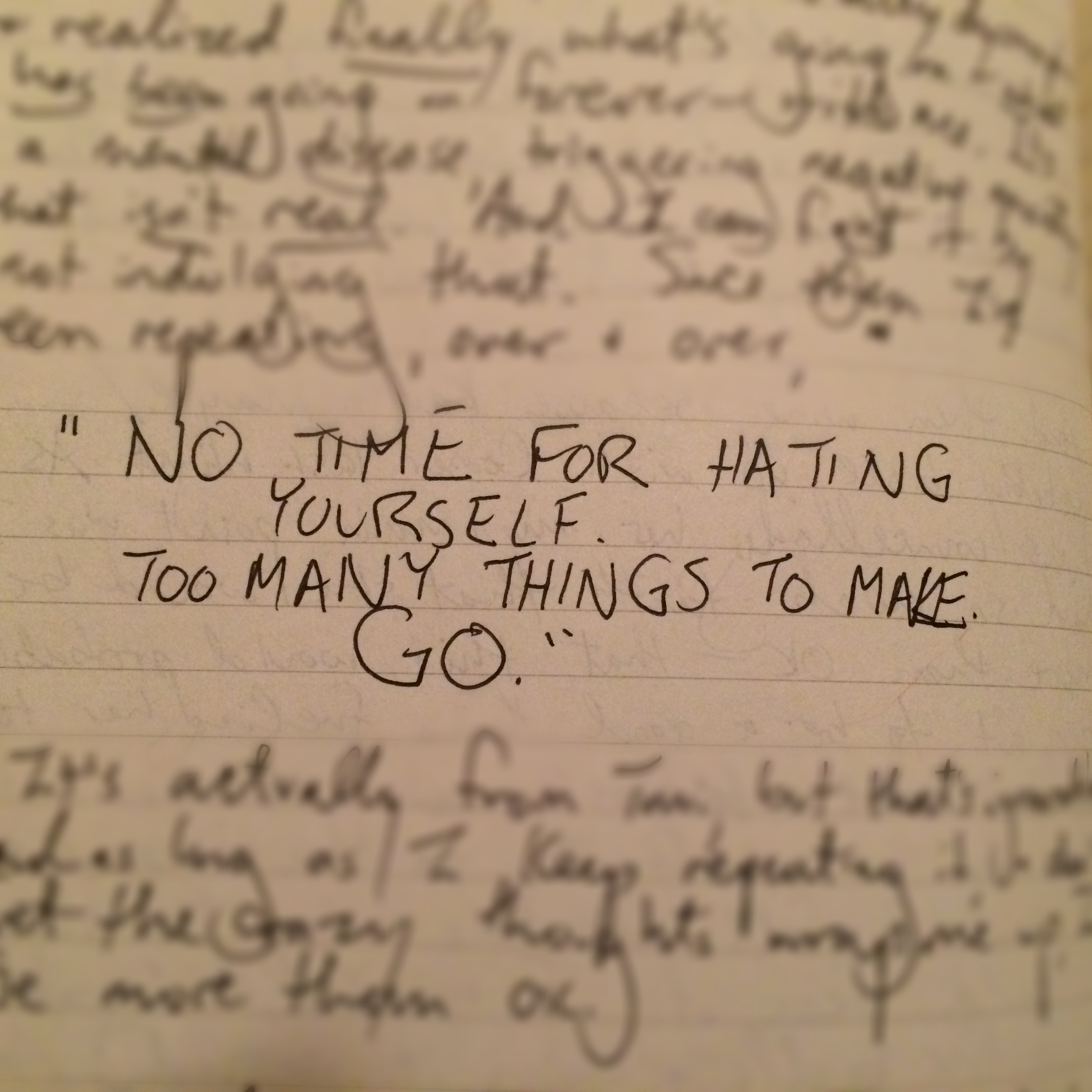

Another is an aphorism that I found on the source for all aphorisms, Tumblr. It is a photo of a piece of paper that the feminist teen blogger Tavi Gevinson had taped to the back of her door. It read: “There is not enough time for hating yourself. Too many things to make. Go.”

I remember seeing it and feeling like someone had just clubbed me with a reality stick. I can’t tell you how many times I repeated those lines to myself through this past year.

“No time for hating yourself,” in front of my mirror on my way out for the night, when perhaps I didn’t feel like I looked my best. “Too many things to make,” on the mat after weekend yoga, getting psyched to go write something. “Go.” On good days, on bad days. Almost every day. I also liked the way it synced with the meme phrase, “Ain’t nobody got time for that,” which had become something of a tagline for my “no fucks given” attitude — adopted as a way to keep my positive, yes-to-life perspective high and distracting negativity low.

These three combined served as driving forces to betterment. If I wanted to be a successful writer with a great life, if I wanted to pursue more creative projects, if I wanted to be the best version of myself, if I wanted to be GREAT and MARVELOUS, then I did not have time for things that could hold me back: sitting and being sad, worrying about what anyone else thought of me or my choices or my work, stressing about how I looked underneath my clothes, thinking about insignificant, small-minded men — or anyone, really — who did not appreciate me. It all went out the window.

Thus, the “NO TIME” tattoo was on my mind for a few months by the time I got it; I had been waiting for something, but I didn’t know what. A little buzzed in a taxi on my way home from birthday day drinks, I decided that was the moment. I redirected the cab, walked into a trusted shop, and scribbled the words a few times in crooked uppercase chicken scratch. I’d never liked my uppercase handwriting — it’s a block-y, barely-held-together sans serif. My lowercase is loopy, a half-print half-cursive hybrid that I’ve always found interesting and pretty. But uppercase it had to be, a stressed point, a shout, a directive.

It hurt worse than any tattoo I’d gotten — fuck the foot or ribs, FINGERS are some serious pain, right on the bone, close to millions of nerve endings. But it was the best one yet, and so worth it. I walked out as the sun was setting over North Brooklyn in that spectacular summer pink-orange array, head clear, feeling maybe one year older but definitely years wiser thanks to those changes in life and attitude in recent months.

Now, the black ink has softened — fading slightly, as finger tattoo tend to do — and it feels more like a firm but gentle reminder, rather than an “or else” angry shout.

Despite not ever believing in mantras or prayer, or at least not the ones I’d seen so far, I unknowingly unwittingly created my own in times when I needed them the most. Two little shout-outs to the universe, establishing my voice in it as one that often wavered but came back stronger, wiser, each time. And written in my own hand, they feel immensely powerful. Like I composed an unbreakable contract to my body to be a better person and signed it to, and on, myself. I don’t think I would feel the same if they were in a pretty font or pre-packaged shape.

I see both these tattoos quite a lot — when I type, when I pee, when I put on rings, when I change my jeans — and when I remember to look at them, I smile.

Because I know, now: I got no time for anything, except a lot of love.

Mickie Meinhardt is a multidiscplinary writer of fiction, essays, and (for her Brooklyn rent) copy, currently working towards an MFA in fiction at The New School. She has a weekly cultural longform newsletter, The Interwebs Weekly. She tweets sometimes but Instragrams often.

For seven students, the first graduating class from the Zabuli Education Center, tonight brought the future, a dream, and tears. At 12:30am EST on December 12th, Razia Jan, the founder of ZEC, stood in the front of a room full of family, friends, and students and welcomed everyone to a very special day. "It's beyond my hope," she said in between the tears, "and my dream that we would be sitting here today with our first graduating class."

The entire ceremony was live-streamed on YouTube, which was coordinated by Beth Murphy, director of the forthcoming documentary about the construction of this very dream, What Tomorrow Brings.

The ceremony was as moving as it was historic, with readings, speeches, and dances from the youngest students to the girls' teachers. But there was also the unexpected: when the seniors were receiving their diplomas, one student rushed past the principal and Razia Jan toward her diploma out of seeming nerves. After some hugs and laughter, Razia Jan paused to tell the story in English: this student, age 14, was the youngest of the seven to graduate. After she sat down, a man stood up and spoke for a little while. What he said wasn't translated, but after the ceremony, Beth Murphy stood in front of the camera to tell us what had happened: her father had stood up to express his gratitude to the school and Razia Jan for providing his daughter with a future. His wife, and her mother, had died suddenly a few months earlier, but she was there in spirit, and in her daughter's strength. Though we couldn't understand the words he was saying, it was obvious the feeling he was conveying.

Watching this all from my Brooklyn apartment, it seems odd that the handwritten word is what connected us with this school and these students, but then I realize that this is exactly what the handwritten word does: it connects and conveys something deep and universal, translatable or not.

We were humbled and happy to publish the girls' story and letters, but also to provide people with the opportunity to write back to them. Please visit the exploration here, and if you feel as moved as we did by reading their handwritten personal statements to a college that didn't yet exist, write them a note back. We can't send snail mail, which is why we exist: to send Handwritten letters.

A long-distance congratulations to these seven inspiring students, Razia Jan, Beth Murphy, and everyone in Deh'Subz, Afghanistan. Some live-streamed images captured below:

BY SARAH MADGES

Kathy Orf is a calligrapher living and creating in St. Louis, MO. She has been practicing a “morning writing” ritual in which she sits down and draws in calligraphy without any prior planning for just a few minutes each day, a 365 project that allows her to continually approach her work in fresh ways. I had the chance to talk to her about what exactly calligraphy is, how it relates to handwriting, and how she became so invested in the art.

SARAH MADGES: How and when did you first become interested in calligraphy? How did you come to make a career out of it?

KATHY ORF: I had a “decorative arts” class in high school that included calligraphy and — I’m really dating myself here — macramé! Then in college, I majored in graphic design and had a whole semester of calligraphy, which was really rare. After graduation, I worked in graphic design until my second son (Alex) was born and then decided I should stay home and do calligraphy part time. I had started trying to sell my work at arts and crafts shows just 3 months after my first son was born and thought I would continue that. I’m not sure I would call it a “career,” maybe more of a passion or a creative outlet…It is really hard to support yourself doing calligraphy and luckily I never had to. That said, I’ve been doing calligraphy for 30 years.

MADGES: When people hear the word calligraphy, they tend to think “beautifully ornate handwriting” or “wedding invitations.” How do you characterize calligraphy — is it an art form, a process of symbol arrangement, pimped-out handwriting? What are calligraphy’s essential elements? What makes it different from handwriting?

ORF: I think calligraphy can be different things depending on how it is used. It can definitely be an art form…something which has been a struggle to achieve in other’s eyes. But it can be very utilitarian when it is used to address envelopes or fill in names on pre-printed certificates. I do not consider calligraphy to be hand-writing in any sense of the word. It takes years of practice and good instruction and some talent to reach a certain skill level. Calligraphy is not fast in learning it or its execution. The letters may look like they’ve been written quickly, but many times it is more deliberate than you might think. And the funny thing is, one important part of hand-lettering is consistency, but whenever I look at printed lettering, I look to see if the letters are identical to determine whether it is hand-done or a typeface. So, even though you strive for consistency, you also want it to look organic, like it came from someone’s hand and not a machine.

MADGES: Does your handwriting resemble your calligraphy? Have you always had good handwriting?

ORF: My handwriting is the worst…just ask my husband. But I think it is because I am always in a hurry when I am writing something and using a ballpoint pen. Put a calligraphy nib in my hand and it’s a different story. It’s almost like my hand knows what to do at that point.

MADGES: Do you have one main mode of calligraphy, or are you always inventing and adapting the letters and symbols to their specific purpose and environment?

ORF: I know many different hands…italic, uncial, blackletter, foundational, romans, copperplate…and variations of them all. But I tend to get in ruts and use the same personalized style all of the time. I guess you could call this style my “calligraphic handwriting” because that is what I use to write with most of the time. My tool of choice to create this lettering is a pointed pen…Brause EF66. It is very flexible and can be used to write very tiny or even letters up to an inch tall. Every morning, I pick up my Brause, a piece of paper that I had already painted and just write a saying using this “handwriting,” although it does not resemble my actual handwriting at all. But, when I sit down to do a finished piece, I might think more about what I want it to look like, and what style I should use, and even use a chiseled nib, like a Mitchell.

MADGES: What are your most common assignments — and what kind of clients do you attract? How long do you spend working on individual pieces?

ORF: Most of my work of late is just doing sayings for friends. I don’t advertise, except through word of mouth. I have some certificate work for Washington University in the spring and fall, and will do a wedding or two a year, but usually just for friends, as I’ve never really enjoyed the rote nature of the work. I also create pieces to sell at fairs using my photographs of things that look like letters that I combine with my calligraphy. I can usually do a simple lettering job in a couple of hours. If I am creating a background and lettering a larger piece, it takes maybe 6 to 8 hours — it really depends on so many variables.

MADGES: What do you think about the diminishment of handwriting and cursive lessons in U.S. schools? Have you noticed any change in the demand for and reception of calligraphy as handwriting diminishes in use and popularity?

ORF: I think it is terrible that they are trying to stop teaching handwriting in schools. I think it is one of those things that they will later decide was detrimental to cognitive development. I’m not sure diminished use of handwriting has affected the popularity of calligraphy as much as the increase in fonts that look like it!

MADGES: What are some of your favorite examples of calligraphy in general — historical, global, etc.?

ORF: I just went to see the Book of Kells this summer at Trinity College in Dublin and it was amazing. I also love the work that Donald Jackson did on the St. John’s Bible that he just completed a couple of years ago for St. John’s Abbey and University in Minnesota. But I am mostly drawn to and excited by contemporary calligraphy.

MADGES: Why do people respond to it? Do you think there will always be a demand or desire for calligraphy?

ORF: I think people respond to calligraphic work because it so often interprets words in a way that touches them. Sometimes it’s because it is something they “wouldn’t have the patience for” — I hear this very often. And sometimes just because it is beautiful! I think there will always be a desire to do calligraphy as art, maybe not as much of a demand for invitations and such, although the whole retro movement may help, like it has for letterpress printing! But to survive, I think it will have to grow more into the realm of art and it has been doing that for a while now.

MADGES: Any advice for calligraphy enthusiasts out there?

ORF: Join your local calligraphy guild. Learn from good teachers and don’t just take a class and never do it again…practice or do homework if it is assigned. The best thing I ever did was to take a year-long class taught by a calligrapher named Reggie Ezell. He travels to four different cities for one weekend of every month of the year teaching almost everything you need to know. The great thing is that there was homework each month, and I DID THE HOMEWORK…and that made all of the difference! Unfortunately, Reggie is retiring after next year. But that was the best investment of time and money I ever spent.

Hello everyone!

I am a student in 12th grade at ZEC. I want to go to college because I attend different events. When I know the value of knowledge I started to dream about goin to college. My greatest wishes to become a teacher in the future. A good teacher is like a candle it consumes itself to light the way for others. Education means to me freedom from stereotypes. With college degree I will have future opportunities. By getting education I will solve my problem and help other boys and girls in my village. When I have a daughter I wish her to be educated and serve to her homeland. Thanks.

Best wishes

Negeena Mir Anas

If you would like to write a letter to Negeena, please do. Send it to us at info@handwrittenwork.com, and we will showcase it above, so she can read your reply & words. We will post our replies beginning on December 12th, the day they graduate.

* For information about this project, see our note at the bottom of the page *

Hello everyone!

I am a student in 12th grade at ZEC. I want to go to college because I make friends last year when I heard about college I started to dream about going to college. Education means to me the most powerful weapon wich we can use to change the world. With college degree I will always be marketable. By getting education I will have less problems and able to solve them. I teach other girls in my village. When I daughter I wish her to be educated like me and have a bright futur. Because if there is no struggle there is no progress. My greatest wishes to become a doctor and help my family and people. Thanks

Best wishes,

Rafeha Ogamuddin

A Note from Handwritten (December 6, 2016): This comes from our exhibit, When I Know The Value of Knowledge, I Start To Dream. We brought the story and letters of seven students from Deh'Subz, Afghanistan into 4th grade classrooms in Brooklyn, because that is when the girls first started school. When they became the first to graduate from high school, they had no college to go to, so they hand-wrote personal statements to a school that didn't exist. Yet. Their letters created an impact campaign that raised $150,000, enough to build the first-ever free private college for women. When we told our 4th grade students about this story, the above, heart-melting letters were their replies.

Hello everyone!

I am a student in 12th grade at ZEC. I want to go to college because it increases my level of knowledge and will learn more. when I know the value of knowledge I started to dream about going to college. My greatest wishes to become a judge when I complete my education. Now I am very lucky and luck is not in our hands, but decision is in our hands. Luck can’t make our decision but our decision can make luck…

Education means to me freedom of speech. And can defense from our right. With college degree I will have a strong sense of pride and self. By getting education I am able to stablish a house teaching for those who deprive from getting knowledge in my village. When I have daughter I wish her brilliant future too. Thanks.

Best wishes, Shakira Mohammed Saleem

If you would like to write a letter to Shakira, please do. Send it to us at info@handwrittenwork.com, and we will showcase it above. We will post all replies beginning on December 12th, the day they graduate.

Hello everyone!

I am a student in 12th grade at ZEC. I want to go to college because I achieve independence. When I was in grade 10th and heard that in 2016 we will start our collage from that time I started to dream about going to collage. education means to me freedom from poverty. With college degree I will have more access to resources.

By getting education I my self will solve my problems without some one help, and can teach other boys and girls in my village. When I have a daughter I wish her to be educated like me. I am the first girls in my family to get education. My mother is illiterate and I am lucky to help her. I want to become a prosecutor when I complete my education. and serve my people. Thanks.

Best wishes Mursal Abdul Raqib

If you would like to write a letter to Mursal, please do. Send it to us at info@handwrittenwork.com, and we will showcase it above, so Mursal can read your reply & words. We will post all replies beginning on December 12th, the day they graduate.

Hello every on!

I am a student in 12th grade at ZEC. I want to go to college because I will meet many of my best and new friends. When I know the value of knowledge I started to dream about going to college. Education means to me learning something new. With a college degree, I will make more money. By getting education I will be able to solve my problems and I can teach other girls in my village. When I have a daughter I would like to let her go to school and wish her a brilliant future. I am the first girls in my family to get education. Because my parents are illiterate. When I was a student in a public school before joining ZEC I couldn't able to read, write even couldn't write my name. Now I am very happy and lucky to read and write. Thanks.

Best wishes, Breshna Abdul Ghanee

If you would like to write a letter to Breshna, please do. Send it to us at info@handwrittenwork.com, and we will showcase it above, so Breshna can read your reply & words. We will post all replies beginning on December 12th, the day they graduate.

Hello everyone!

I am a student in 12th grade at ZEC. I want to go to college because I will have some fun. When I know the value of knowledge I started to dream about going to college. As every one know that knowledge is power. Education means to me to have a better future. With a college degree I will have more in come. By getting education I will increase the level of my knowledge. I can solve my problems and help others. When I have a daughter I all her to go to school and wishing her a brilliant future with great achieve ments. An illiterate person is like a blind which sees all the universe dark. So learn knowledge from cradle to grave. My parents are illiterate. I am lucky to help them. Thanks.

Best wishes, Yalda Hameedullah

If you would like to write a letter to Yalda, please do. Send it to us at info@handwrittenwork.com, and we will showcase it above, so Yalda can read your reply & words. We will post all replies beginning on December 12th, the day they graduate.

Hello Everyone!

I'm a student in 12th grade at ZEC. I want to go to college because I will learn more. When I understand the value of knowledge I started to dream about going to college. Education means to me to find a good job. With a college degree, I will have a lifetime of increased opportunities. By getting education I won't have problems. I can teach younger siblings in my family and other girls in my village. When I have a daughter, I will let her go to school and wish her a bright future. I am the first girls in my family to get education. My parents are illiterate. I joined ZEC since 2008 and learnt more. Now I know I have changed a lot. Before coming to ZEC I had problems at education. I am reall lucky, thanks.

Best wishes, Aziza Toryalong.

If you would like to write a letter to Aziza, please do. Send it to us at info@handwrittenwork.com, and we will showcase it above, so Aziza can read your reply & words. We will post all replies beginning on December 12th, the day they graduate.

The instagram does not exist. In it, a patch of white-gray sidewalk frames a loose circle of dead leaves. In the top left corner, the curb of the road. At the center, yellow graffiti. The graffiti is a crooked arrow pointing into open space, and next to it the words FAG PARKING. You can tell from the way that FAG is scrawled the graffiti first marked something else, that when the text was painted it wasn’t graffiti at all. There are other signs nearby: a pink flag, some white tubing. But there it is, revised: FAG PARKING.

I came across the parking space on a run. On shorter runs, anywhere from 30 minutes to an hour, I perform the same loop. I run from my apartment on Ditmars Boulevard to the northernmost avenue in Astoria, then west to Astoria Park, around the park, back to the avenue, and home. I’ve run the avenue hundreds of times. And then this drab, fall day, as I near the top of the hill that marks its middle, I find the inscription. I must have been sensitive that day. The sky was clear and pale, the wind was calm; I’m full of pride, I’m well adjusted. And yet. FAG PARKING. I feel that hot and unmistakable pang: shame.

A photo posted by Justin Sherwood (@justin.sherwood) on

And then I think, let this be funny. I’ll capture the image and say, “If you’ve ever tried to find parking in Astoria, you know how considerate this is.” The day passes and I go for another run. As I crest the hill, I keep my eyes peeled for the graffiti. I must have missed it—I’ve passed the place I know it to be. I’m nearly in the park and there’s no sign. I make a small circle, run back up the hill, nothing. I stop at the top to catch my breath. Another sideways glance, then down.

Justin Sherwood's poems and essays have appeared in Women's Studies Quarterly (WSQ), New Criticals, H_NGM_N, and The Poetry Project Newsletter, among other places. He's also a contributor to Scout: Poetry in Review. He teaches at The New School, where he received his MFA in Creative Writing. Find him on Twitter @JustinSherwood.

Karen Benke is a creative writer, adventurer of pen and paper, and long time poem-maker. She is the author of the chapbook, Sister (Conflux Press, 2014), and three popular books on playing on the page, Rip the Page! (Roost Books/Shambhala, 2010); Leap Write In! (Roost Books/Shambhala, 2013); and Write Back Soon! Adventures in Letter Writing (Roost Books/Shambhala, 2015). She lives north of the Golden Gate Bridge with her teenage son, a magic cat, and a rescue dog. Though she prefers receiving letters via snail mail, she can be reached via her website: www.karenbenke.com.

What happens when it's not just you, the writer, who struggles with the screen, but your characters? In this lyric essay, Tonianne Bellomo walks us through the negotiations she makes with her characters. What does she do to bring them to life? She builds them paper homes.

Read More