SARAH MADGES: So I wanted to talk to you about your process, how handwriting figures into it, and how you came to incorporate it into your process:

ANGELA FLOURNOY: Handwriting has always been a part of my process. I got my first journal when I was eight years old — I don’t have them with me or I’d check, they are at my mother’s house. I’ve always worked out ideas or feelings through handwriting.

For most of my academic life I was writing papers on the computer and generally typing things, and it didn’t seem like the most natural way to work on something that was not like a term paper. When I was first writing short stories in undergrad most were written on a computer first, but when I got to Iowa, one thing that was an issue for me was procrastination. I didn’t have the smartest of phones, I was always a couple generations behind — now that’s an issue — but I figured if I left the house I’d focus more. So I would sit in the coffee shop and sit on my laptop hanging around on the Internet instead of writing, even after downloading Self Control, because you could still override it.

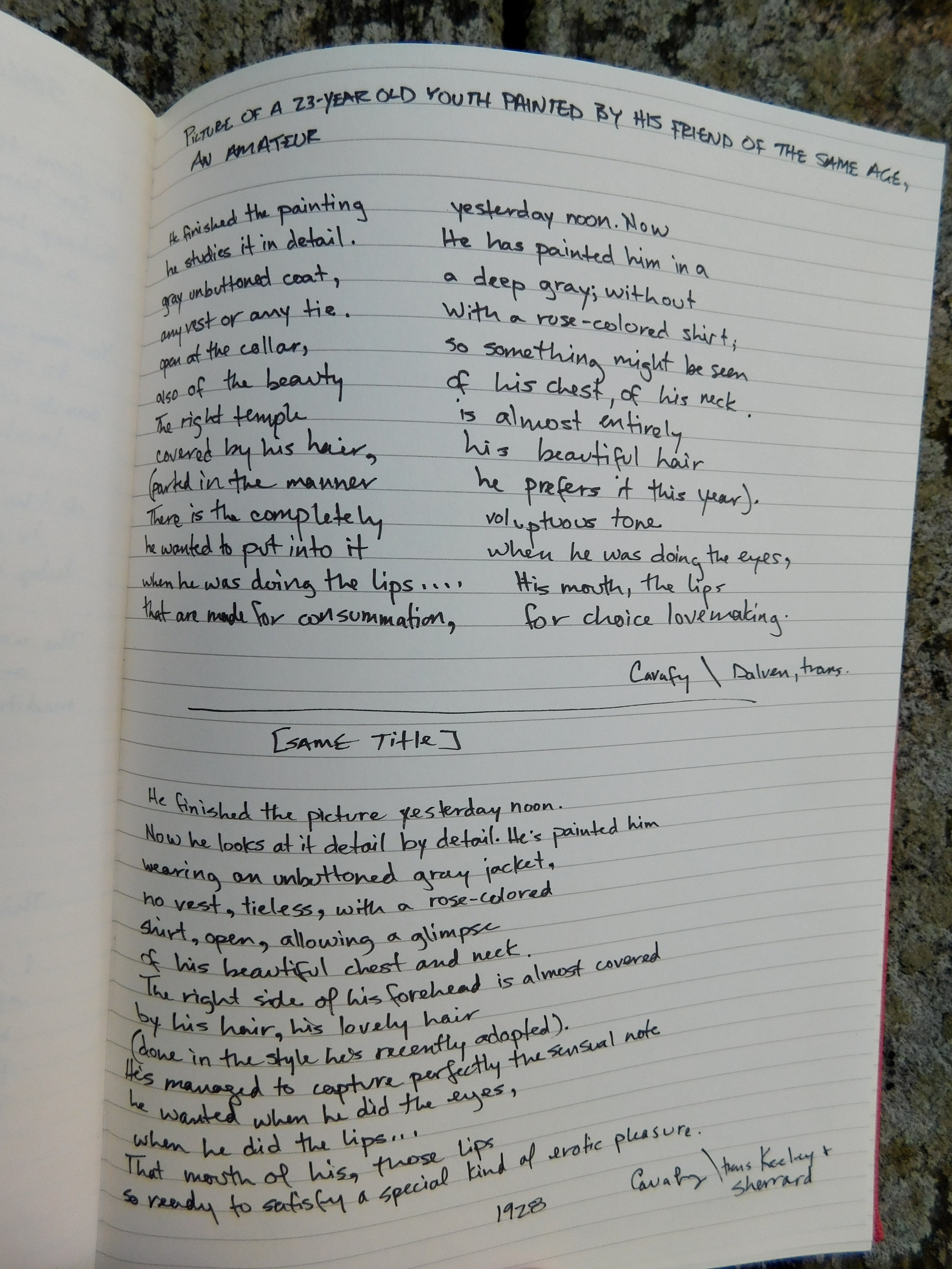

So I returned to handwriting to focus — there were not as many distractions. Especially when you’re working on something historical, you want to look everything up on Google, which is useful in revision, but it gets in the way of writing when you stop and end up in a Wikipedia rabbit hole. Writing longhand made me focus, and slow down.

MADGES: Has your writing always been historical in the way The Turner House is, or written about, for example, a city you never lived in, but know about?

FLOURNOY: History is always a part of the way that I envision stories. This novel, especially, but I had written 70 pages of another novel based in a city I never lived in and it was a similar process.

MADGES: How would you get yourself to push through the writing instead of succumbing to the kneejerk reaction to look things up — would you leave notes like “look up later” and just keep going?

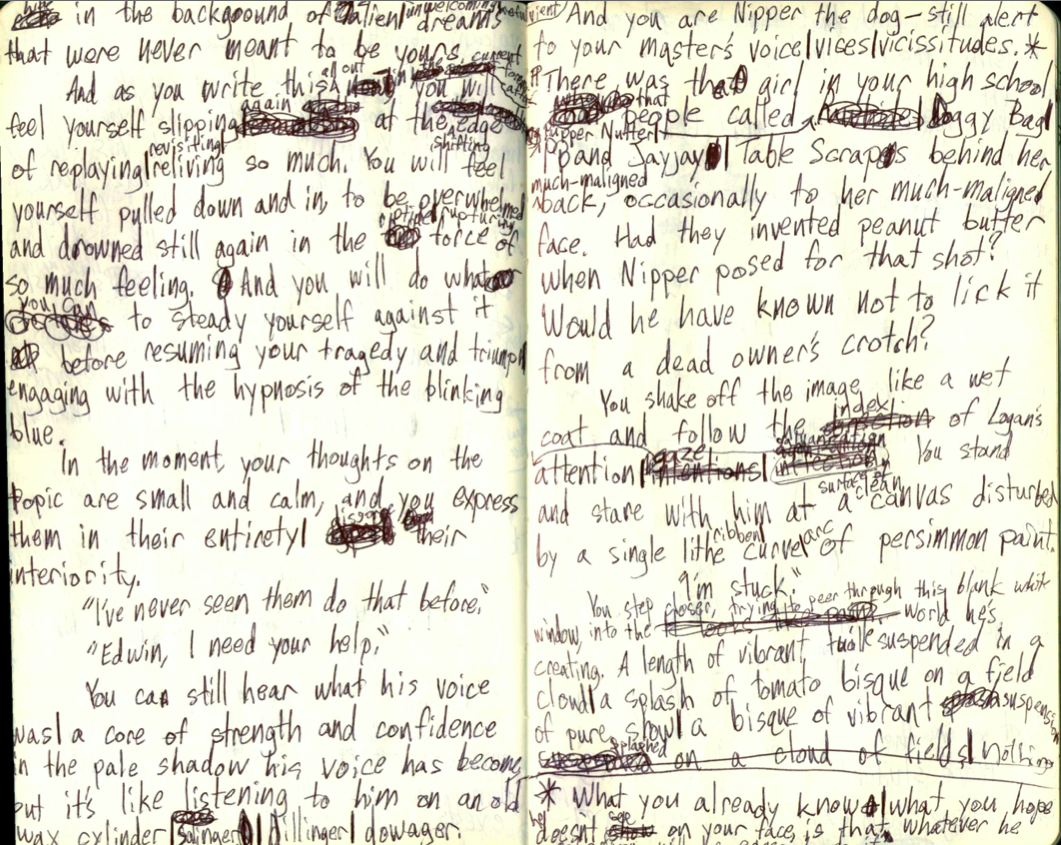

FLOURNOY: Well I would put an asterisk next to what I wasn’t sure was right. The thing about literary fiction is that it’s not one of those things — I’m not writing a civil war period piece that heavily relies on research and that people are so into it and will feel betrayed if they feel it’s inaccurately portrayed, like, “That’s not what happened at Gettysburg!” That’s not the burden of the kind of fiction I write. You just need to have a foundation with reality. I would just write in the margin: Look this up!

MADGES: You said you started writing in a journal when you were around eight years old. Did someone encourage you to do that, or did you sort of come to that naturally?

FLOURNOY: Well, it was a Christmas present from an aunt of mine and so then it was just, there. And I’ve always been a person who, as soon as I learned how to read, read a lot, so it was like of course I would do this thing. No one was telling me I have to do it, and there wasn’t much else to do. Now, we live in a time of distraction, so it might be different. People talk about wanting to pick it up as a practice.

MADGES: Did you always prefer to write by hand? Have you found greater success this way, or did you notice yourself writing/editing differently with a word processor?

FLOURNOY: I feel like I’m a lot less apt to take risks when I’m typing out a story because it’s so easy to delete things; whereas, when you’re writing by hand you have to get to a certain critical mass before you “x” something out. It’s too easy to reread every sentence, go backwards rather than forward.

The editing process should be the editing process. You handicap yourself when you keep cutting down your own ideas. One on its own might not be great, but they might all make sense in concert with themselves. When there’s that blinking cursor encouraging you to cut them down, you might lose what the idea was really supposed to be.

MADGES: Right! And once you delete them there’s no evidence of those ideas, at least in a notebook you can usually still read the words you crossed out. So how does handwriting figure into your writing process? What role did it play in writing the Turner House?

FLOURNOY: One benefit of writing longhand, I’m more gentle with myself on first drafts. It hurts to scratch out all the pages you wrote in the day.

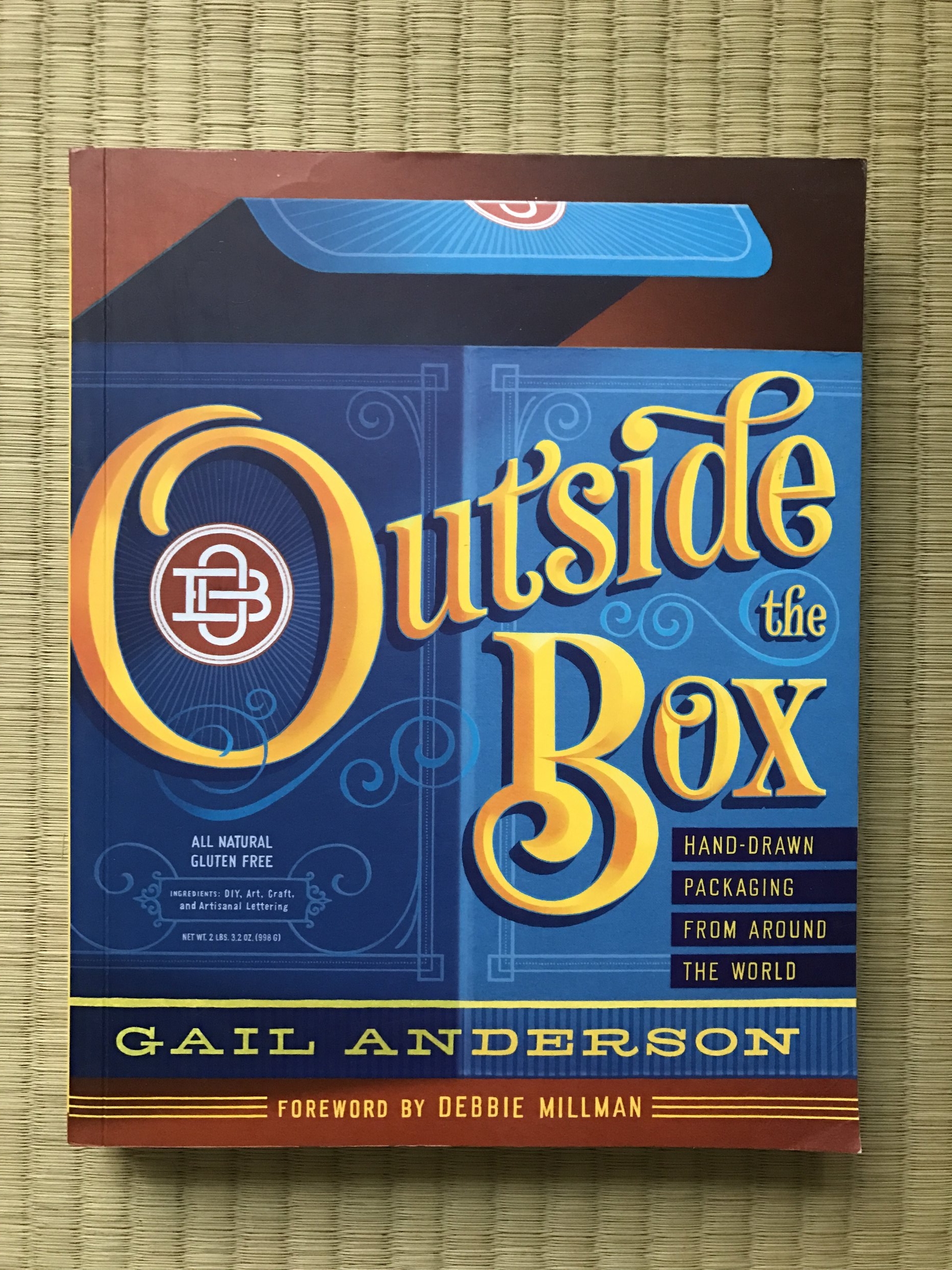

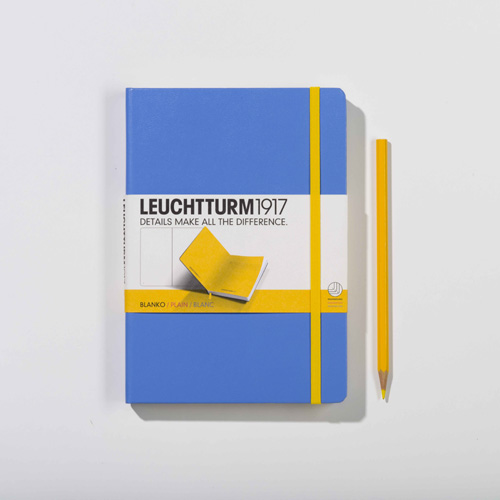

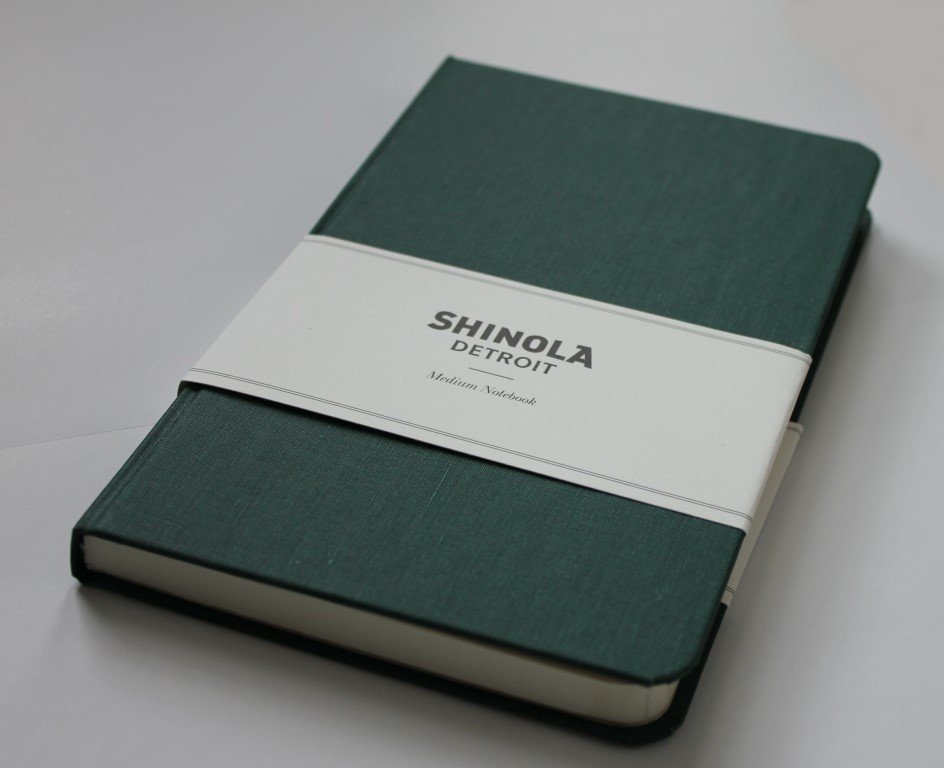

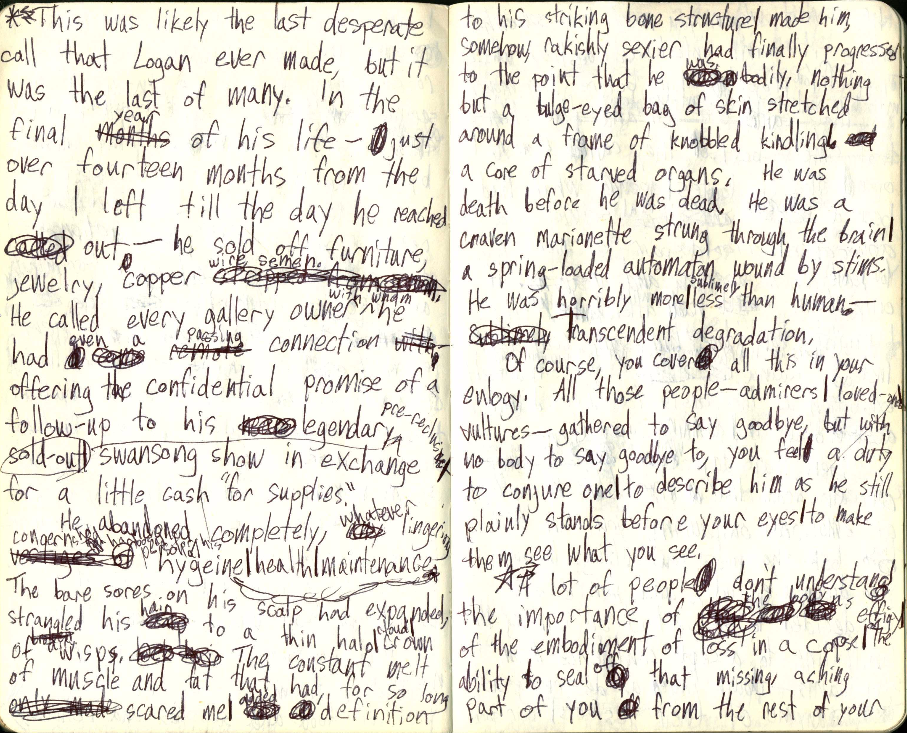

I usually write the first draft longhand with notes in the margins and sometimes rudimentary edits as they fit on the page. For this novel, I wrote maybe a couple chapters at a time, then I would go and type them into this master novel document. That’s already two editing processes: on the page in the margins, and then of course I’m not going to transcribe something that is terrible, so again when I type. And because I’m not rereading everything in the document, that document lives separately, it ends up getting sort of built up and I’m able to look at what’s there, what’s working and what’s not, and change it later. It allows me to have a base, and provides some time between writing something and wanting to jump into revising it and moving, structurally, whole chapters around. Once I finished a notebook I would assess: where are we actually in the larger narrative? Some of the notebooks are half writing prose, half notes. It took about seven college ruled Moleskine notebooks.

MADGES: How long would it take you? Did you find yourself having to stop because you couldn’t physically write anymore, or…?

FLOURNOY: No, I’m not a fast writer. On some days, it might have been more staring and thinking and I maybe only wrote five actual pages in my notebook. On other days, I could very easily look up and there’d be 15 pages in front of me. And even though handwriting is larger, those 15 pages would end up being 20 pages because I would think of things to add or subtract when transcribing. I don’t really remember my hand cramping. I wish I was one of those people who could really get a lot out of writing for three hours every day. For me, I have “writing seasons” and I have “thinking about writing seasons,” and when I am in the writing season, I just hunker down. I wake up early. If I don’t have a block of four hours, I feel like the time is already gone. I am not a fast writer. I was working at a D.C. public library, and I would have a shift from 5-9pm. So I would get to the coffee shop at noon and I would try to finish, or start a chapter.

MADGES: Do you keep a journal, or carry a notebook and pen around with you?

FLOURNOY: I have a journal but I don’t write in it much. When I was writing short stories, I would sometimes journal, but when I was writing this novel, I think the last thing I wanted to do was pick up another book and write in that book, too. I have slowed down journaling for myself. Now, I use it more for marking moments, or milestones.

MADGES: How do you feel about the fact that cursive is no longer required teaching in U.S. elementary schools?

FLOURNOY: I am terrible at cursive — I have terrible handwriting — but I can read cursive. But say, how can you even read archival documents if you can’t read cursive? You have to trust someone else’s transcription of it. It’s as if you’ve lost a language if you can’t read it for yourself and that is dangerous because people can say that any document says anything. It’s bad enough I only know one language fluently — I can at least read and write in Spanish — but it’s bad enough that most people in the U.S. don’t even have reading proficiency in a second language. But to not even have that proficiency in the language you were raised with? We’re not even going to be a monolingual culture anymore — we’re going to be whatever half of monolingual is.

MADGES: Well, you had a very successful debut! How do you feel about being shortlisted for the National Book Award? Were you surprised?

FLOURNOY: Yes, I was surprised. A sort of big moment for me was being on the long list, because who thinks that’s going to happen? I was in my apartment and I had sorted out my clothes and was going to take them to the laundromat and my phone started vibrating. This is stuff your younger writer self doesn’t dare fantasize about. I never really fantasized about publishing my book in general. It’s been great — it’s opened up all these different opportunities. I’m going to be teaching at The New School in the spring, which is exciting.

MADGES: Did you write about that in your journal?

FLOURNOY: [laughs] Yes, the last thing I wrote was in, like, August, and then: “I got on the shortlist!” It starts to look like a timeline, not a journal. Baby steps. I’ll get there.