Braiding Together Our Lives

Bretty Rawson

A project that weaves together generations, experiences, and handwritten expressions.

Read MoreSince we aren't on every social media site, let us come to you. Enter your email below and we'll send you our monthly handwritten newsletter. It will be written during the hours of moonrise, and include featured posts, wild tangents, and rowdy stick figures.

Keep the beautiful pen busy.

Brooklyn, NY

USA

Handwritten is a place and space for pen and paper. We showcase things in handwriting, but also on handwriting. And so, you'll see dated letters and distant postcards alongside recent studies and typed stories.

search for me

A project that weaves together generations, experiences, and handwritten expressions.

Read MoreIs the notebook half-empty or half-full? In this essay, Joyce Chen sets out to test and trust her hand, a routine tethered to time, with the hopes of avoiding the pitfalls of resolutions by resolving to reflect. Are you up for the screen test?

Read More

BY CHAD FRISK

I don’t know about you, but my mind is a disaster. Things are constantly whizzing through and then clogging it up. Things proliferate and congregate, ideally like constellations in the sky but typically like commuters during rush-hour. It’s a mess. Writing is, as I see it, the process of making that mess suitable for display. I learned the hard way that there is an appropriate tool for each step. I wrote the draft of my first novel by hand. I thought it would be cool. It was actually very dumb.

I filled fifteen notebooks. I went through a dozen erasers. Oftentimes I chose not to revise because it would be too much of a pain to cross things out and scribble in the margins. When I finished, I typed the whole thing into a Word document anyway, one indecipherable page at a time from tiny, gold-tooled notebooks that refused to stay open on their own.

I didn't know what it was about when I started writing. One day, I walked past an old, abandoned clock shop and thought it would be interesting to write a book about time travel. That was my only idea. I bought a notebook, scoured my apartment for a pencil, and started writing.

I was living in Japan at the time, working at a junior high school as an assistant teacher. That year, I didn't have anything to do. It was my job to go to four hours of class a day and read from a textbook. The other four hours were my own.

I decided to write a book. When it was finished, it had nothing to do with time travel. In fact, it had very little to do with anything. It was four or five stories posing unconvincingly as one, scrawled across 100 Yen notebooks I purchased at convenience stores.

There was a psychiatrist. He was frustrated by his patients' lack of progress, and decided to pursue alternative therapy - which included breaking and entering, kidnapping, stalking, and mild psychological assault. There was a burned-out business man. He was so deep in self-help that he had lost sight of how good he already was. There was a server at a nightclub for the uber rich. She was tired of getting hit on by three-piece suits, but was making so much money that she had convinced herself it didn't matter. There was a ten-year old boy. His grandpa had died, leaving a hole in his after-school routine that he didn't know how to fill.

There were others. There was a detective possessed by the ghost of Dick Tracy, an old illusionist whose understanding and lifelong exploitation of cognitive biases had poisoned his view of humanity, and a girl who lived in a castle with a mother and father who didn't pay attention to her. There was also a beanstalk, a ruined city, and a sleeping giant.

It needed an almost complete overhaul. To do that, I abandoned my pencil for a keyboard. Computers are amazing because they make editing incredibly easy. Point, click, drag, delete. Done. It’s infinitely easier to revise already written words on a computer than on a pad of paper.

It took me about eight months to handwrite the first draft. I spent nearly an additional year revising it. I cringed while rereading my notebooks. The story didn't make any sense. Who were the characters? What did they want? How were they connected? What was the point?

From the flurry of keystrokes, slowly, something that could be called a narrative emerged. I knew that it wasn't good enough, but I tried to get it published anyway. After a half dozen rejection letters (and at least as many unreturned emails) I gave up.

But I had something. It was all thanks to the computer. Revising the original text by hand would have been impossible.

But I'm glad I started with pencil and paper.

Handwriting is good because it can go all over the place. Impulse is where my writing starts, and it’s easier to transcribe impulse with a pen than a keyboard. I can scribble, doodle, draw lines, cross things out, and generally be very messy. Out of this mess emerges something coherent enough to take to a laptop.

The process of refining continues digitally, because that’s what bits are good for. I find that the first step in mining my mind, however, is often best performed by hand.

Chad Frisk is a graduate student at the University of Washington working towards a Masters in Teaching English to Students of Other Languages. His books include Direct Translation Impossible: Tales from the Land of the Rising Sun, which was published in October of 2014; a Japanese version of the same to be published in March of this year; and and he's working on his next book - this time entirely on a computer. His website is nobodyelsewillpublishme.com.

His grandfather hadn't been to a bar in forty-seven years. An interesting details until his grandfather reveals another forty-seven year secret - one that was kept from him, and now kept from others.

Read More

BY SARAH MADGES

I am often asked, “What are you going to do with all of those?” in regards to my ever-amassing collection of notebooks.

The tone people adopt when they ask me registers as an accusation, or a warning that they’re going to turn me in to the reality show Hoarders’ producers and stage a televised intervention. True, the amount of notebooks I’ve accumulated makes moving daunting (the journals, both blank and filled-in, take up at least four standard file boxes, and are heavy). But these bound batches of scribbles mean the world to me. Because it isn’t just the words that matter — the content ranging from teen angst to amateur poetry to higher ed revelations — but the format. The tangibility. The way the words look on the page. The way my handwriting sometimes forms tight serpentine ribbons or grows looser and larger when tipsy or tired or both.

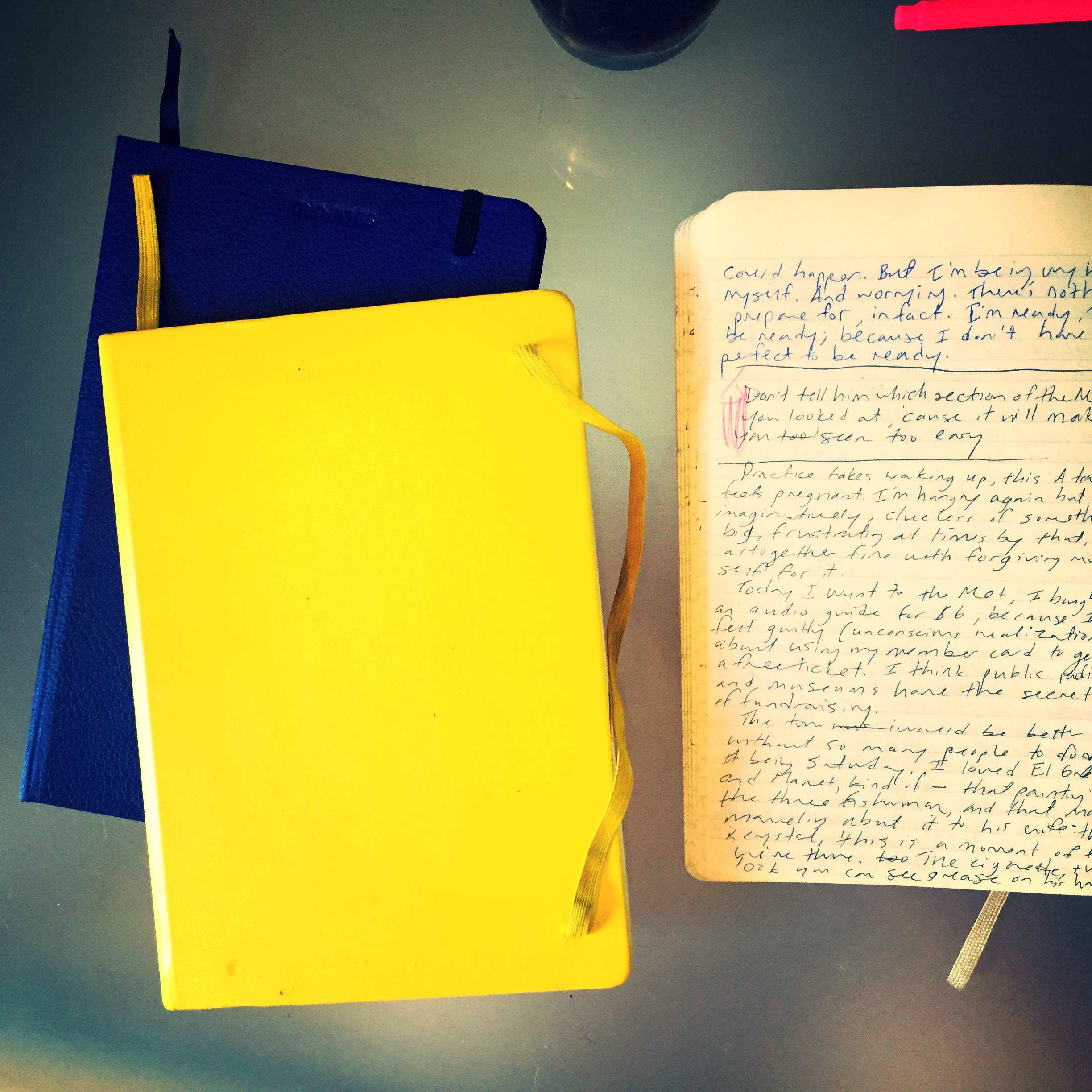

The materials matter; even the notebook choice tells a story. Moving chronologically, my notebooks upgrade in quality from flimsy composition notebooks (Harriet the Spy-grade Meads) or one-subject college ruled notebooks I also used for high school Trig, to those ubiquitous ribboned moleskines, or Germany’s analogue, the Leuchtturm, or even the notebook in which I composed this draft—a Stamford Notebook Co. lizard embossed cobalt beauty handbound in England.

The medium change means a few things: 1) I moved up one ladder rung in the service industry and could afford nicer products, 2) I was starting to take myself seriously as a writer, and each double-digit-$ notebook was an investment in that continued pursuit 3) other people were taking me seriously as a writer, and gifting me nice notebooks for holidays 4) I realized the paper quality, brightness, and thickness, all contributed to the actual look of the text.

I began to appreciate the aesthetic of each individual journal entry, independent of the actual written content.

BY BRETT RAWSON

As a kid, I preferred to cruise in crowds and tell stories in front of audiences. I didn't like to read or write. By eighth grade, I had left both far behind: my reading and writing levels were three years behind me. I remember my mother used to turn on the microwave timer for thirty minutes, pleading me to read, if not just look at, any book. I'd say of course, she'd walk away, and fifteen minutes later, I'd approach the microwave, and press five buttons one second apart, mimicking the end of the thirty minute session, and with not so much as a be back later, I'd be running down the street toward a cul-de-sac of activity.

But in between two rice paddies, around the age of twenty two, I discovered the wild noise and absurd worlds that existed inside me. By simply putting thoughts to paper, new universes of ideas came flowing forth. Each night, as I sank into these stories, I found a sense of relief in a new kind of silence: writing by hand. In the beginning, most were about the everyday, but I recall many faraway thoughts. I ran after each, even if it meant brushing up against a vanishing point. I didn't always make it back to where I began, but I also realized that wasn't the point. I was supposed to be, or perhaps get, lost.

A decade later, my closet is the only one complaining about my now daily practice. The process itself is about processing, and during stretches of time when I am not handwriting enough, I feel the difference in my mind. The distraction, echoes, and pressures. They build up if I don't clean things out. There is continuity is all the connections: these kraft brown journals. I have a few that exhibit some decorations, but those are specifically journals I keep to write about writing. When I open up these covers, I walk inside an open. And in that undisclosed place, nothing has to make sense.

Didn't we just discover a new planet? We're always discovering new planets. My telescope is just pointed in a different direction.

WORDS FOR WALLPAPER is a kaleidoscopic force of creative decoration by Chicago-based poet and creative, Andrea Rehani. It combines the beauty and brevity of poetic expression with an artistic and aesthetic simplicity that is at once reminiscent of the modern and the antique.

Beginning by hand, Rehani creates a poem based upon a particular color or theme and allows them to take horizontal and vertical shapes as she frames them for the wall, where they will eventually live. There is an odd distance of intimacy to Rehani's work. The poems themselves contain a layer that can feel like a memory, but zooming out, the object itself represents something of the "now here," not "nowhere;" in that, they carry with them the sense of place that surrounds them.

To see the exhibit, click here.

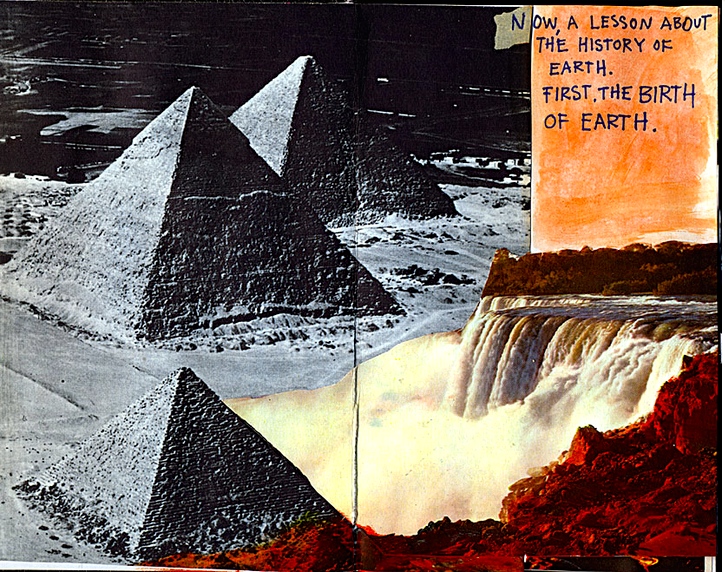

Brian Singer is a San Francisco-based fine artist whose sobriquet “Someguy” downplays the enormously unique body of work he has produced in the last decade or so. I first discovered his work at age 15, when I stumbled across the 1000 Journals Project book in my sister’s bedroom.

An ongoing collaborative experiment, The 1000 Journals Project attempts to track 1000 originally empty journals through their travels across the globe, accumulating stories, sketches, and photographs as they pass between friends’ and strangers’ hands. In addition to larger scale projects such as this, he creates visual art pieces that explore the layers of signification of the printed word, crossing out and redacting text in a process of mixed media décollage.

SARAH MADGES: The extensive, anonymous shared artifact network you created with The 1000 Journals Project speaks volumes about individuals' desires to be creative, without fear of criticism. Did you expect to find so many untapped talents waiting to give expression to their thoughts? Did you initially conceive of this project as a way to make collaborative art or did it just kind of happen?

BRIAN "SOMEGUY" SINGER: I think everyone is creative, but society tends to have a narrow definition of the word. Some people are creative when they cook, or garden, others make art. In the book Orbiting the Giant Hairball, Gordon MacKenzie talks about creativity—I’m paraphrasing here—he says that if you ask a room full of kindergarteners how many of them are artists, they’ll all raise their hands. Ask the same question of a bunch of 6th graders, and a few will raise their hands. Ask high school students, and you’ll be lucky to get a couple to raise their hands. So, what happens to us growing up? We begin to fear criticism and judgment of society.

When the project was conceived, it was based on what people write on bathroom walls. Not quite collaborative art, but more like public conversations. That said, I love the works of Dan Eldon, and sort of imagined what would happened if people just layered and layered their contributions until you got a density similar to his journals.

MADGES: In an increasingly tech- and text-based world, handwriting has lost some of its former relevance and ubiquity—cursive is no longer even required in U.S. school curricula and thousands of people have never written or received a letter in their entire life. How important is the handwritten aspect of these journal entries to you? How important is the written word to you as an artist?

SOMEGUY: The hand-crafted element is crucial to the journals. It’s almost like a signature, or hint of a person’s personality, beyond the words written. As an artist, for whatever reason, it has a little less meaning to me. Strange, now that I think about it. Perhaps because it’s so accessible and anyone can do it, it feels less precious or unique. Or maybe because I don’t incorporate handwriting into my art work — I’ve never really liked the look of my own handwriting. It’s more like chicken-scratch, which I blame my dad for.

MADGES: Do you keep a journal?

SOMEGUY: No. Yes. Sort of. I don’t keep a journal the way most journal artists do. When I was younger, I kept a journal which was more like a diary of sorts. Now, I have sketchbooks, which I use mostly for notes and ideas. Not really for freeform writing, or artwork, just lists and notes and sketches.

MADGES: As far as I can tell, the 1000 Journals Project was last on exhibition in Scottsdale in 2013. Where is it now? What are your plans for the project? Do you consider yourself its curator anymore?

SOMEGUY: There aren’t any exhibition plans for 1000J right now. A couple years back, I approached a few venues, and while there’s some interest, nothing panned out. As for plans, again, I don’t have any current plans. This is mostly due to time constraints, it takes a lot of energy to keep things going. I do consider myself the curator of the project, but am mostly playing a waiting game.. waiting for journals that have been out in the world for almost 15 years to be rediscovered and sent home. I imagine most are sitting on bookshelves, forgotten over the years.

MADGES: What do you think is the relationship between visual arts and creative writing? Do you think of yourself as a poet or writer when you create your cross-out and printed word pieces?

SOMEGUY: That’s a great question, because I haven’t given it much thought. I tend to gravitate towards certain types of works. These can be strictly visual in nature, or strictly written. I think the ability to combine the two opens up the best of both worlds when done well. They can live in harmony, or in contrast, and add value to each other, or amplify the artist’s intent. When I create my redacted works, I mostly consider myself an editor. I’m stripping away information and creating new meaning. I’d hesitate to call myself a poet or writer, which might be an insult to poets and writers, but there are some similarities in our goals to shape language and message.

MADGES: What have you been working on lately?

SOMEGUY: Lately, I’ve been working on building bodies of work around themes. So not really participatory, or journal based projects. One recent explorations was around visualizing number patterns (connect the dots) in unexpected ways. And the current exploration (no photos online yet), are process based works where I put a shape on every page of a book (imagine a circle or letter), and then cut the book up and reassemble the shape using the edges of the paper.

While some use their journals to capture the everyday experience, Nivi uses them as a space and place for her poetry to roam.

Read MoreA Get Well card from an antique shop that is dated 1955. A cute cat, thoughtful note, and throw-back to getting better, hurriedly so.

Read More

Sarah Madges is a handwriter living in Brooklyn. Her handwriting has appeared in numerous composition notebooks, a handful of three-subject college ruled notebooks, and a whole host of moleskines. She also works with typed words, which have appeared in places like the Village Voice, Killing the Angel, and various abandoned blog platforms.

Wellbutrin blues dose high dose low so close. closet blues

keep shoes rubber made walking. white round scribbles. Avoid

avoids. Walk away stomp shoes bouncing soles black.

colorful hyphen split open particles purged beads of feel

betters scattering scattered. Extend the release of. You might

experience. May include. Talk to your doctor.

Peristaltic magic make me whole soul bouncing.

Internal tremors shake off just wellbutrin blues.

Swallow swallows swallowed shallow breathing blue-

Ing. Better better better better. Walk out old life

matinee movie — much brighter than you

remembered. Glittering goldly sweetly scrim of

saccharine. Put it on peristaltic. Old life moth balls

closet blues forget forgot. Swallowing a white room

quiet white noise machine drown out therapy

drown out but what about tell me about talk

about I. Scratch pad for scars give coat for bag

rattling. Bouncing in bag walking out old life.

Ticking rattler reminder not quite not quite. Quit.

Sarah Madges is a handwriter living in Brooklyn. Her handwriting has appeared in numerous composition notebooks, a handful of three-subject college ruled notebooks, and a whole host of moleskines. She also works with typed words, which have appeared in places like the Village Voice, Killing the Angel, and various abandoned blog platforms.

BY ZACHARY LUTZ

The sketch for “The Bone Transfer” was written in a subway car. Probably the B or the Q, headed to Manhattan. I keep a smaller notebook, pocket-sized, with a white cover. It helps that the surface area is more compact, as well the writing is compacted to fit. Tempts less spectators. In this particular type of free-writing, being surrounded by people comes in handy: there’s no contract for details on the subway. I’ll start with some image that’s been consistent and strange, some reoccurring thought. I’m generally writing narrative work, think non-autobiographical, so I’m not always drawing from experience. Easy to steal from something happening next to me on the train and makeup the rest.

The day I’m taking notes that will eventually turn into “The Bone Transfer,” I’m thinking about cartoon physics, TV tropes. For a few days, I’d been scanning this website/catalog of TV tropes, stumbling through entries. ‘Toon physics got me hooked. The page for the trope made note of “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” as being a good example of the crossover between the “natural laws” of the human world versus that of the cartoon, and thus a good reference point for demarcation. I wanted to write something where character(s) experienced cartoon physics in the human world, but maintained their very human portentousness. I had been thinking for some time about how cartoons experience electrocution.

In addition, I’d received a phone call from a BBQ restaurant earlier that day assuring me that if I were to return to the location any time in the near future, I’d have a free meal voucher waiting for me. It was a wrong number call, but stuck with me. The writing I’m doing in my notebook is really just a way to process details. I try work with specificity as often as possible, and to link those details that might at the start appear un-linkable. (A rerun of an episode of “Shark Tank” introduced me to the Uro Club, which is referenced here alongside another sex organ-themed gift. It all returns to the body.)

When I transpose from my notebook to my computer, I’ll edit as I go. I’ll cut whole sections out, rearrange syntax. I change names or pump up the ambiguity. I want always for the mood of the piece to overshadow the context. Writing or thinking through a piece by hand provides me a necessary freedom which I make freer by movement—a faulty retractable leash that keeps threading out, a series of handkerchiefs from the sleeve of an encouraging magician. I recognize themes in handwriting, leave structure for the word processor. The shearing that results from the unmerciful typing-up of handwritten notes helps manage a pace, become more economical, say more heavily.

Zachary Lutz is a handwriter in Brooklyn. He holds an MFA in poetry from The New School and received an honorable mention for the Paul Violi Poetry Prize. His work has appeared in Luna Negra Magazine. To the left is his handprint.

An inland letter that speaks of a generation when emotions, family values, morals and ethics were placed before the concept of individualism.

Read MoreInside the weathered covers of Rainer Maria Rilke's 1954 The Way of Love and Death of Cornet Christoph Rilke, lies a very human note.

Read More

In early Spring of 2015, Sarah Madges set out on a project surrounding the Handwritten word and recalled Brett mentioning a project he had recently begun. She reached out to ask if the project was still alive. It was, barely. The exchange served to reignite the project and has since turned into this site, which Sarah is also to thank for, as she since came on board as a central curator for the project. Below is their initial exchange about the idea for the site you are seeing today, which is constantly evolving.

SARAH MADGES: What inspired you to develop a publication/project surrounding the handwritten word? What is your own experience with handwriting?

BRETT RAWSON: I knew I wanted to start something last winter. I took a course at The New School that had us look at digital storytelling, and I found great calm mixed with wild energy in this embrace of and attitude toward technology - how can we use technology to promote our passions, digital or otherwise? On a morning in February, I was on the L train brainstorming for a separate project when the word Handwritten appeared from somewhere. I had my notebook in hand so I scribbled it down. I happened to be heading toward a workshop put on by PEN, so I wonder if that had something to do with the whole thought. At any rate, the word opened up the idea itself: a home for the handwritten word online.

There is no place that publishes things other than finished products. I wanted to promote process. There's a bunch of theories and thoughts about handwriting, penmanship, and personalities. I do think about them, and I care about them, but I am not specifically concerned about them. I don't really care much about their outcomes or conclusions. For example, I find it interesting what people think my handwriting says about me, but I care more about saying things with and through my handwriting. What comes of it in the end is not really something I can consider while I am doing it.

The idea is pretty simple—for people to express themselves with pen and paper, and be published for it. It's also to be a preserve of sorts—for letters written by those who have passed, for example. I am always writing by hand. I don't always write my stories by hand, though most things usually begin on paper—in a journal, on a napkin, or a legal pad. I do, however, write a lot of letters. It's how I ease myself into writing for the day. I can't jump into writing on the computer without starting by hand. I have to start somewhere free. In this sense, it's like stretching, doing yoga, starting out slow, or warming up.

MADGES: What is the project's mission statement?

RAWSON: A place in space for pen and paper. But I have been thinking about changing it to something a mentor of mine once said: writing is a physical activity.

MADGES: Are you concerned that handwriting / cursive lessons are being eclipsed by keyboard proficiency lessons in U.S. elementary schools?

RAWSON: I'm not so sure I am that worried about cursive. But that's probably because mine is horrific. In fact, my regular handwriting sort of looks cursive. Or maybe it looks like it is cursing. It's hard to tell. Someone once said my handwriting looks like a string of wasted wingding characters, which is offensive, but true. But handwriting altogether, what a horrific waste of natural talent. The hand is how we gain access to our inner self. I really don't think the computer can access that wild, raw energy inside each of us. When using a computer, I get an external feeling (usually in the form of mild swells of panic), whereas when I write by hand, the noise from everywhere really quiets down, and I can finally hear my own voice.

The people making these policies, or mistakes, probably don't write by hand much. I imagine they see it as a waste of time, or something of the past, that we should get with the times and technology. This measurement feels imprecise. And it isn't a matter of sentimentality. It also isn't about one or the other. I wonder when people will wake up and coexist - to stop living in some world of ones. I write on the computer all the time. I have four twitter accounts, a Facebook profile, page, and group, five Instagram accounts, one tumblr, and three websites. You know? It's not like I don't get the beauty and power in the computer, let alone its efficiency, insanity, and amusement. I am a user, and I love using it. But what a fucking mistake to not teach kids how to write by hand. So I guess I am concerned.

MADGES: Do you notice a difference in the kinds of things you write when you use pen/pencil as opposed to a computer / word processor? How do you think the writing tool affects content/style/etc? How do you think it affects the editing process?

RAWSON: Absolutely. The medium affects everything. The effect is also bilateral. The reader adjusts his or her expectations based on the medium. A letter is sort of like dining out—there is an experience to it. An email is more like take-out, delivery, or TV dinner - it is often more quick, requires less from me, and can be done while doing something else.

That being said, I don't see it as a matter of good or bad, better or worse. It is simply different. Writing by word processor is more about a product or outcome—a finished something—and so pieces composed there are usually toward that end. But with handwriting, it is more so a work of progress, or process. It is, inherently, more private and intimate. Computers are meant to connect, gather, and scatter. And the screen in between becomes a kind of reflection and projection, which can be a disorienting feeling that registers at a deeper level. Handwriting is about process on two levels -- one, it is about the process, but two, it is a way to process things. Not necessarily produce a product.

MADGES: Phenomenologists have argued that the self falls away when we are engaged in an intense activity, usually one that collapses the sense of the mind-body split by activating both elements. Do you think the writing implement of choice could act as a bodily extension, and that writing by hand helps combine subject and object in ways that promote intimacy with a text, whereas typing into a word document promotes separateness of subject and object?

RAWSON: Fascinating. I imagine this has to be. There is a oneness when it comes to things like painting, the piano, or even running, and so it would make sense that it carries over to hand-writers. It makes me think of meditation for some reason, only I don't really know why. There is intense freedom within limitation, which might be why the computer is such an energy vampire. It pokes so many holes in our concentration containers that after a short period of time, we feel totally drained. Whereas with the handwritten word, I think of a dam and what happens when everything flows through a single thing—it harnesses a new kind of energy. Because with handwriting, you aren't concerned really with what you're writing. There is something hypnotic about the way in which the hands moves.

MADGES: Anything else you would like to add?

RAWSON: Keep the beautiful pen busy!

handtyped by Brett Rawson

HANDWRITTEN BY JENNY CURRIER, LIVIA MENEGHIN, AND DEIRDRE SCANLON

handthinking by Brett Rawson

I have kept this card closely for eight years now. When I moved to Unalaska Island, I brought it with me. When I went on sixteen mile runs across the island's jagged terrain, I brought it with me. At points when I felt lost in confusion and fog on those runs, I pulled it out and read it. This postcard has, in a sense, become my traveling talisman. Perhaps it is because of the words - after a long night's parade into the wild fantastic. Or perhaps it was the unexpected reception that etched its way into consequence. I was living in a town of eight thousand in rural Japan, and when I returned home for a brief visit, this card was awaiting my arrival. I brought it back with me, and it was around then that I began to leave more room for mystery in my daily life. I was not surprised to find out, years later, that my uncle has long been writing, and writing primarily postcards.