Gwen Beinart's Teiglach • Charlene Beinart

Bretty Rawson

Note from Curator Rozanne Gold: What a lovely surprise to receive this beautiful story all the way from New Zealand. Psychologist Charlene Beinart learned about “Handwritten Recipes” while listening to a podcast of “A Taste of the Past,” hosted by culinary historian Linda Pelaccio. The show, recorded in a hip studio at Roberta’s restaurant in Bushwick, Brooklyn, managed to tickle the tastebuds of a childhood in Durban (South Africa.) How I love that connection! Teiglach (also spelled taiglach) is a sweet treat eaten on Jewish holidays, but most popular for Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year). This recipe is particularly fascinating to me because the teiglach of my youth were small balls of pastry boiled in honey and stuck together in pyramids with bits of candied fruit. Gwen’s teiglach are, instead, large, oval rings of pastry afloat in amber syrup. Who needs to wait for a holiday?

BY CHARLENE BEINART

My mom, Gwen Beinart (nee Sackstein), born in 1936, has always been the heartbeat of my love for baking. Over her lifetime she gathered a collection of recipes handwritten onto small cards — some her own, and others gathered from family and friends, tested, tasted, and kept as part of her core repertoire.

Of Lithuanian and German Jewish heritage, I am the second generation born in South Africa, and the youngest of three girls. A typical Jewish immigrant history, my grandparents on both sides came to South Africa looking for a better life. They were very poor and my parents wanted nothing more than to give us the best possible life and education. My father was a self-made businessman and my mother was a very creative homemaker.

Of all of her recipes, there’s one that brings back the most vivid memories of delicious family time: Teiglach. Syrupy, crunchy, chewy donut-shaped biscuits, these sweet offerings were at the centre of every gathering and a symbol of the importance of the occasion being celebrated. This recipe was what my mother was best known for. My emotional attachment to it was so profound that it took me more than 20 years after her death to make them.

I am remembering, from my childhood in Durban, all the many conditions needed to make perfect teiglach. First: the weather. It must be a humid-less, sunny day, because the teiglach got dried out on my parents’ brick-paved patio before being boiled in syrup. Next: the equipment. You had to have the right pot, with a heavy metal lid and a brick placed on top to make it completely airtight. Then: no draughts! My sisters and I knew to never open the kitchen door and let in a draught when the teiglach were boiling on the stovetop!

I was always excited when my mom made them because it meant something important was happening! Most likely, we were going to Johannesburg to be with my aunts, uncles, and cousins for Rosh Hashanah or Pesach. Huge round Tupperware containers would be filled with my mom's teiglach and offered as gifts. Everyone made a fuss: teiglach were considered a great delicacy. Best of all, the containers were never returned empty — my aunts filled them to the brim with treats for our long car journey back to Durban.

After my mom passed away in 1991, we (my husband, three sons, and I) moved to New Zealand. Naturally, my mother’s treasured box of handwritten recipe cards came with us. But making teiglach felt far too daunting (emotionally and otherwise) to do on my own. Good results never seemed attainable.

Just a few years ago, when my sister Kerry visited from London, we agreed to set aside a day to (finally!) make my mom’s teiglach. We had her Kenwood mixer, the right heavy-lidded pot, her lengthy handwritten recipe, and we felt her loving guidance — along with that of our other sister Elona, supporting us from England.

The family was well briefed: no opening the kitchen door, no draughts!

Kerry and I put our memories together and got started. Kerry remembered the teigel shape and we molded the dough before setting them out to dry in the sun. I remembered the three-step process to stir the teiglach once they were boiling in the pot: lift the lid, wipe off the condensation, and stir. Do this all quickly (remember, no draughts!) Of course this resulted in many hot syrup burns — scars I wear with pride!

While I always knew making teiglach was far more than following a recipe, I was not prepared for the overwhelming feeling I experienced when we opened the pot of the boiling treats for the first of six stirs. The sweet, syrupy smell flooded me with lifelong memories of love, happiness, and of our beloved mom.

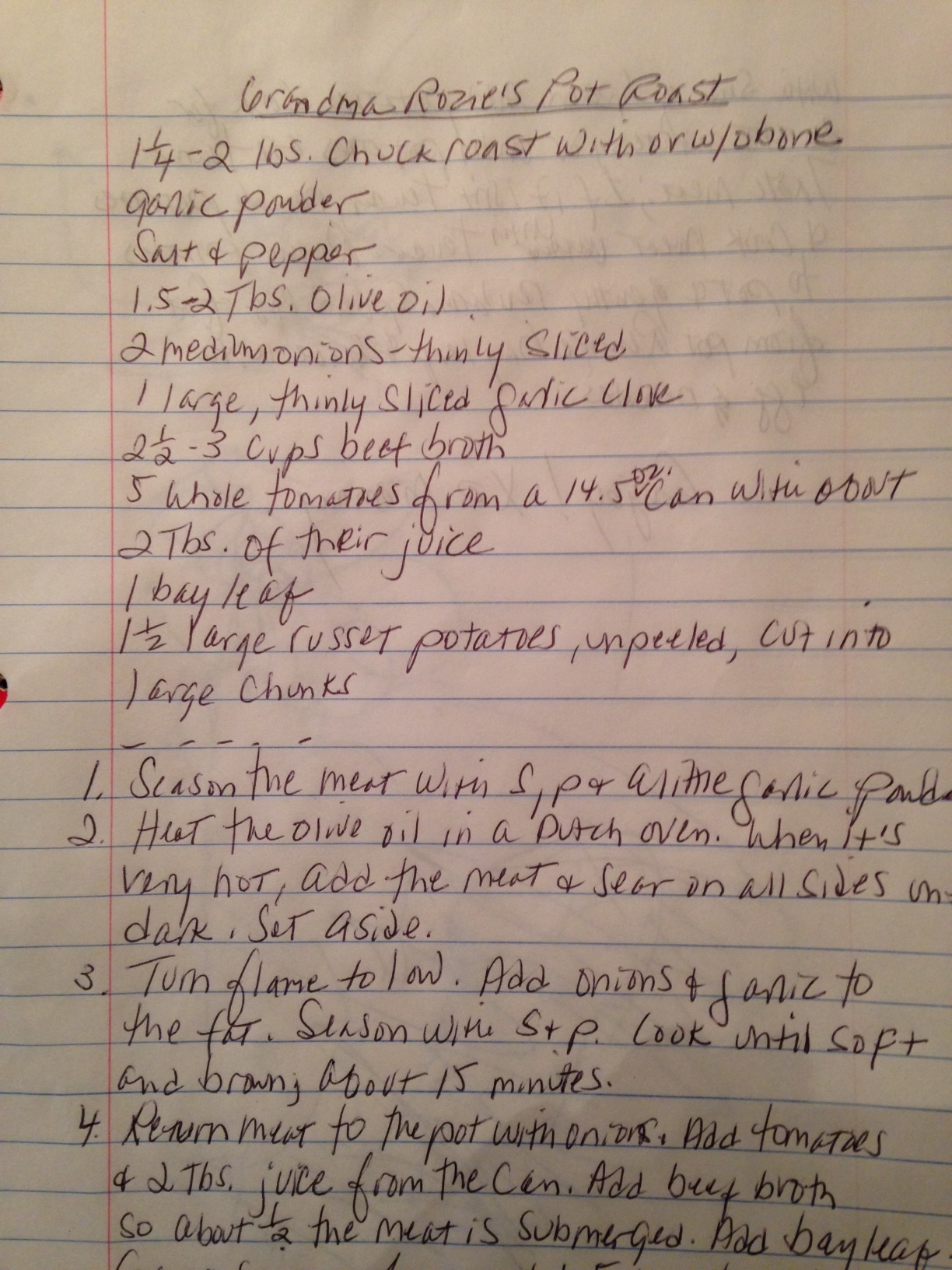

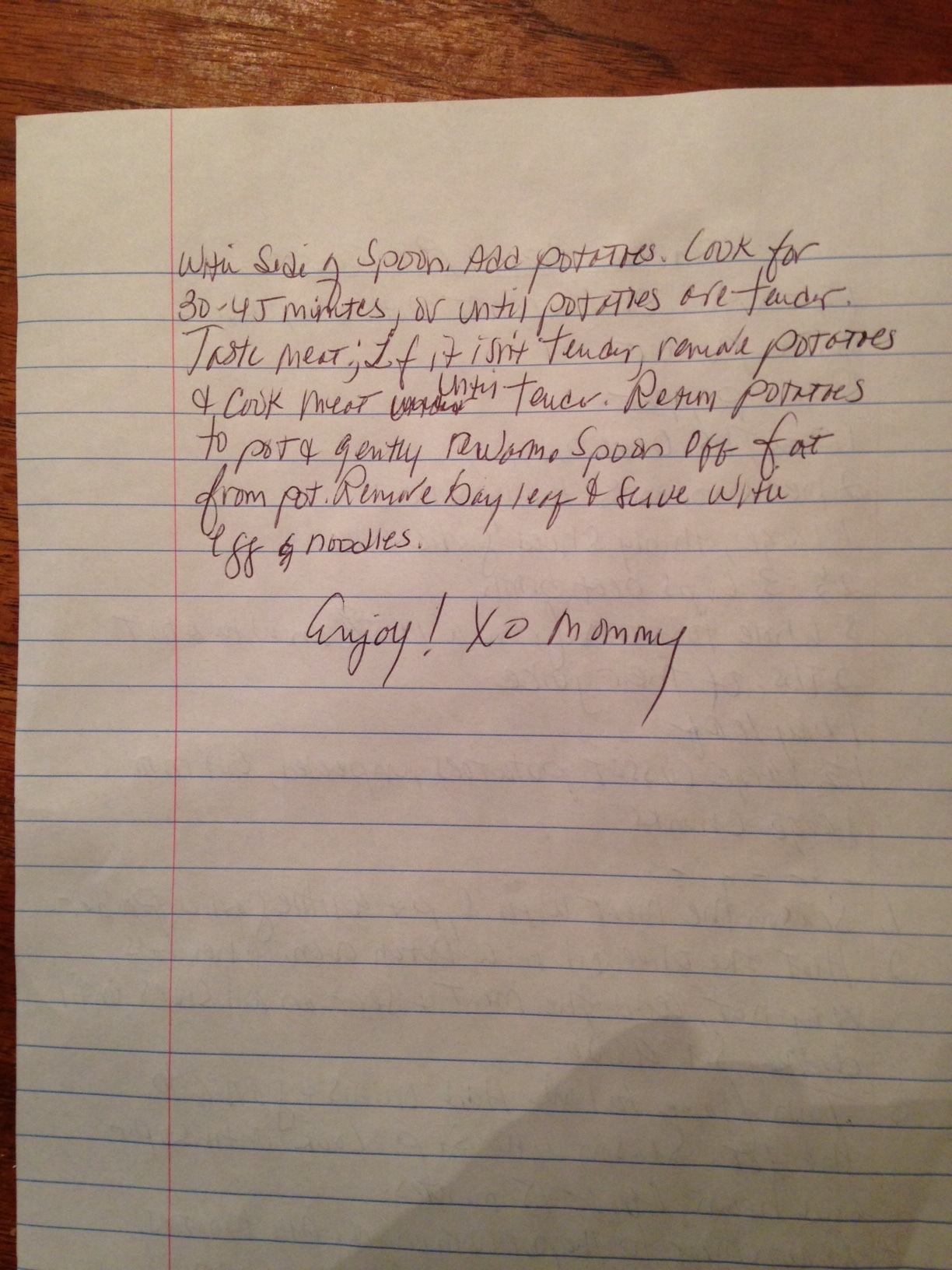

Mommy’s Teiglach (Gwen Beinart)

Note: Adjustments for gas stove made by Charlene

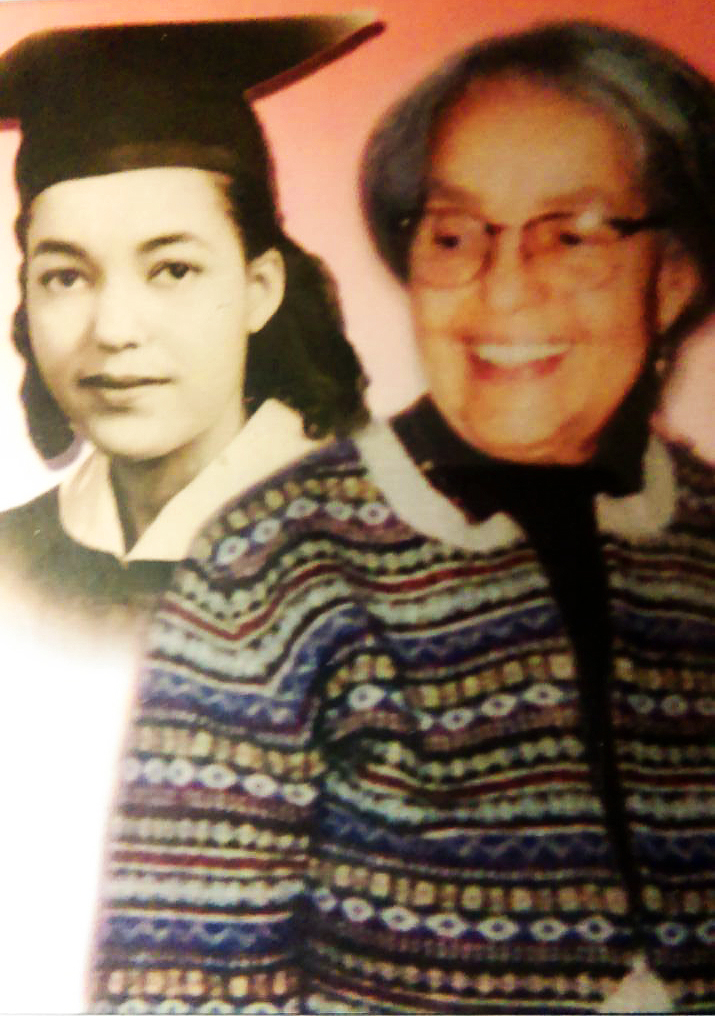

A Photo of Charlene's mother, Gwen Beinart

Ingredients:

6 eggs

1 Tablespoon Oil

1 Tablespoon Brandy

Pinch salt

2 teaspoons grated orange zest

½ teaspoon baking powder

Flour: 3 cups to start

Syrup: 2 lbs or 1 kilo tin golden syrup,

3 cups sugar, and 2 ½ cups water

Directions:

1. Slightly beat 6 eggs with oil, add brandy, salt, orange rind and then baking powder.

2. Add 3 cups flour sifted (one at a time).

3. Take a little bit on a small heap of flour and work in flour until dough is soft, slightly sticky but pliable. Roll into shapes in floured hands.

4. Put into floured tray to dry – preferably in sun for approximately 20 minutes, s turning over after 10 minutes

5. In the meantime, put syrup, sugar and water on to boil in large heavy pot (or weighted lid).

6. When boiling fast add teiglach. Close lid and boil on high for 5 mins

7. Then turn down to medium/high (low to medium on gas) to boil for 30-35 mins (26 – 30 on gas) before lifting lid. (Very important to weigh down the lid!)

8. Wipe lid and stir in quick motion every 5 mins until done (an additional approximately 20-30 minutes, or six stirs). Total time on the stove is 1 hour 10 mins according to Mommy but on gas probably a total of 55 mins)

9. Special note for gas : after 1st 5 min fast boil move pot to medium size plate on medium gas for 30 mins. Then do the lid/wipe/stir @ 5 min interval either 5 or 6 times in total.

10. When done take off 1 ½ cups of syrup for next batch

11. Then put in 1 heaped teaspoon ground ginger andhalf to ¾ cup boiling water down the side of the pot.

12. Stir until bubbling stops and take out teiglach onto damp board or plate. Leave to cool.

13. Can roll in chopped nuts if desired.

14. Store in plastic air tight container.

15. If making further batch add ½ used syrup and ½ new to same other ingredients – usually better

Charlene Beinart works as a psychologist in private practice and her husband is a university lecturer. She writes, "Our sons have turned out to be far better cooks than me, and their interest in food history has captured my own. We are regular listeners of Linda Pelaccio's podcast, A Taste of the Past. Our oldest son is currently a MA student at Hebrew University, researching the lives and stories of Lithuanian Jewish immigrants to South Africa through the cookbooks they created and the recipes they passed down to their children."