Butter Tart • Kari Macknight Dearborn

Bretty Rawson

A Note from Curator Rozanne Gold: This fascinating article by Kari Macknight Dearborn comes just in time for Canada’s huge 150th birthday party celebration on July 1st. Canada Day festivities take place throughout the country and wherever Canadians live abroad. Here, Kari shares her own glorious family history, and that of Canada’s edible icon. Her step-by-step photos for making the country's beloved butter tarts are at once mouthwatering and instructive. Kari, a senior producer at the Toronto advertising firm, Zulu Alpha Kilo, Inc., is a board member of Slow Food Canada and is currently studying for her WSET Diploma. She lives in Ontario with her husband, Paul, and two Hungarian Puli dogs, Luna and Tisza. Many thanks to Allison Radecki for securing Kari’s memories for us...and just in time for the party! Happy Birthday, Canada.

Click to enlarge

BUTTER TARTS BY KARI MACKNIGHT DEARBORN

As so many of my fellow Canucks count down to July 1st, and to what probably will be the largest national party of my lifetime — Canada’s sesquicentennial celebration of Confederation — we are daily bombarded, and in every conceivable medium, with Canadiana.

This fervor has never been seen in our land of quiet pride and polite patriotism, and it’s odd and awesome at the same time. Images of beavers and moose, maple leaves, hockey, and all other symbols of my native land, are everywhere this year. The entire country is red, white, and bleeding nostalgia.

Canada officially came into being July 1, 1867, in case you were wondering what the fuss is about, by being granted a confusing level of freedom from the British Empire. It’s complicated. Americans went about it slightly differently, I know. Canada’s separation from Britain was a lot less bloody, and our connection to the ‘Empire’ is still strong today as a result.

We remain a country with very British and French influences because these countries created Canada. We have two official languages and we’ve raised a bunch of the funny and talented famous people you love. But my story is not exactly meant to be a lesson in Canadian history.

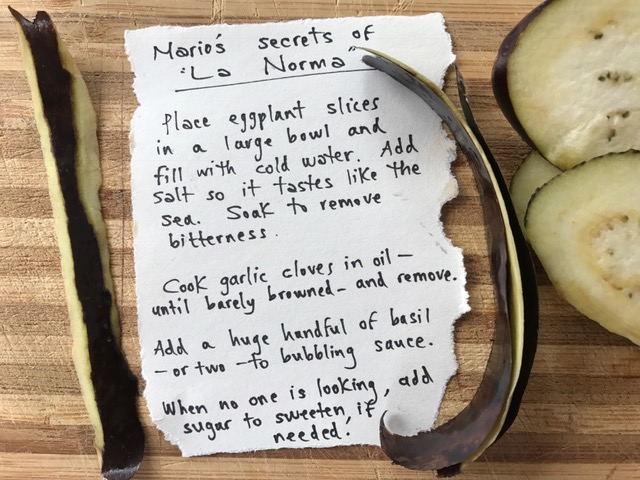

Instead it is a story about a singular confection; a quintessential Canadian dessert, made with basic pantry staples — the butter tart. How it came to be such a part of Canada’s cultural identity, and my own, is at the heart of my handwritten recipe.

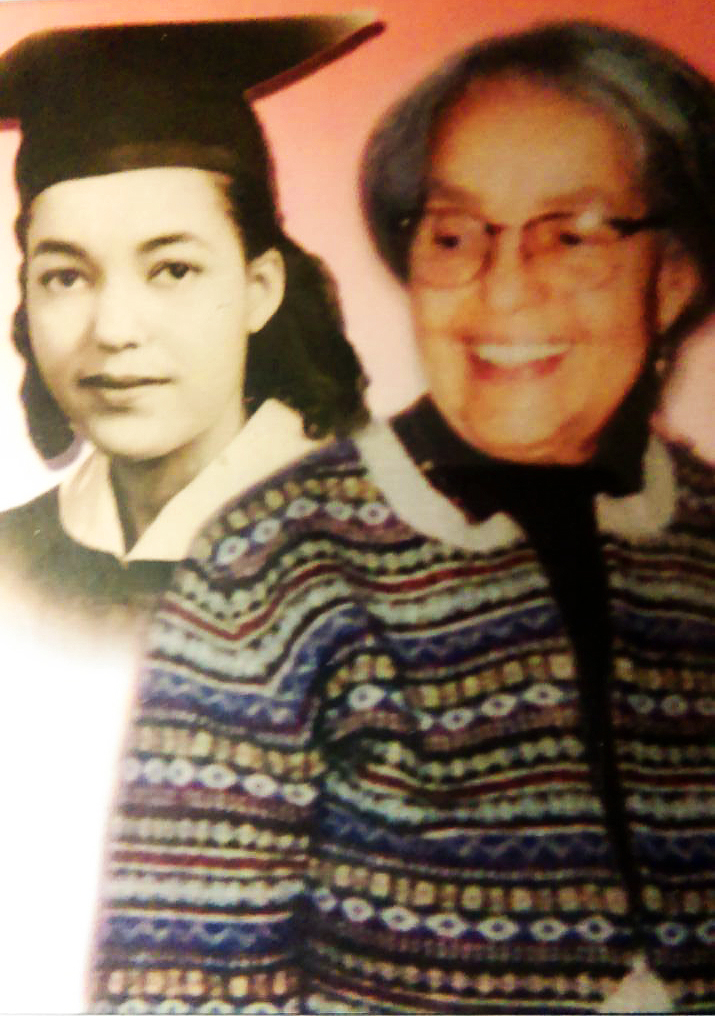

I was raised in Northern Ontario on the North Shore of Lake Huron, as a consequence of my father’s employ in the mining industry. My grandmother was an English war bride who married my Canadian soldier grandfather and came to Canada shortly after the end of the Second World War. They settled very close to what would become my hometown of Elliot Lake.

My mother comes from hard-working Scottish Hebridean farmers of the Presbyterian persuasion, many of whom were displaced by the Highland Clearances. They ultimately settled in the rich agricultural areas north of Toronto that resemble, topographically at least, their ancestral homeland, minus the blasting winds from the North Atlantic.

It was in these enclaves of fellow immigrant Scots, and other erstwhile Brits, where these folks baked for weddings, picnics, and church events with the humble ingredients they could most easily procure.

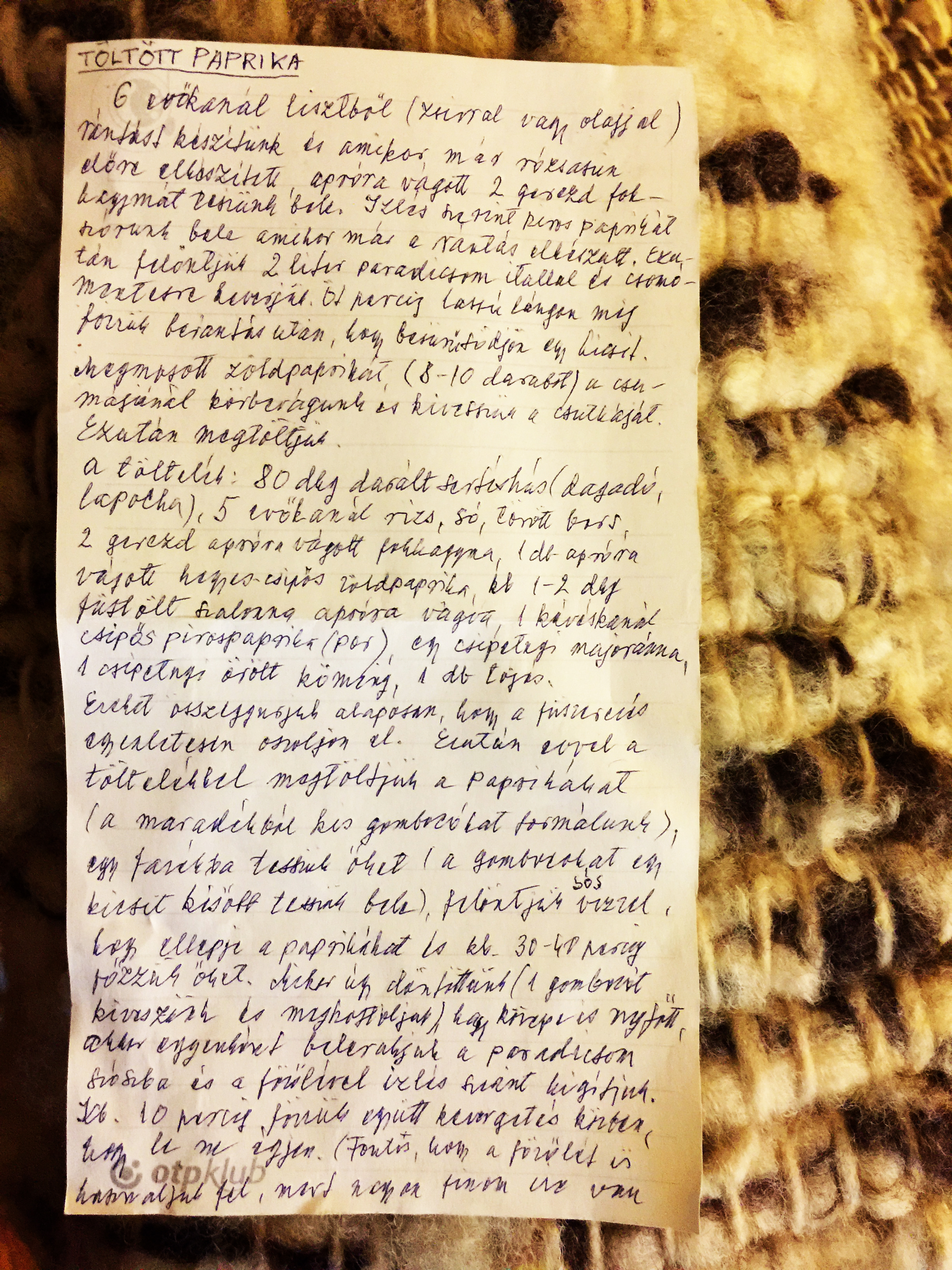

Canadian food historians claim the butter tart’s certain influences from the Scottish Ecclefechan tart and early Québecois pie recipes made with maple syrup and maple sugar, as well as Southern recipes for pecan pie. These reasons all make sense given our country’s history and the oral tradition of sharing recipes. The main difference with the butter tart seems to be the individual serving size. Additionally, butter tarts are runnier than pecan pie given the lack of cornstarch.

The earliest published recipe for the butter tart is from Barrie, Ontario, from 1900 in the Women’s Auxiliary of the Royal Victoria Hospital Cookbook, attributed to one Mrs. Malcolm (Mary) MacLeod. Since my mother’s Aunt Marion was part of the auxiliary in Barrie in the post-war era, the written recipe here, in my mother’s hand, naturally resembles it.

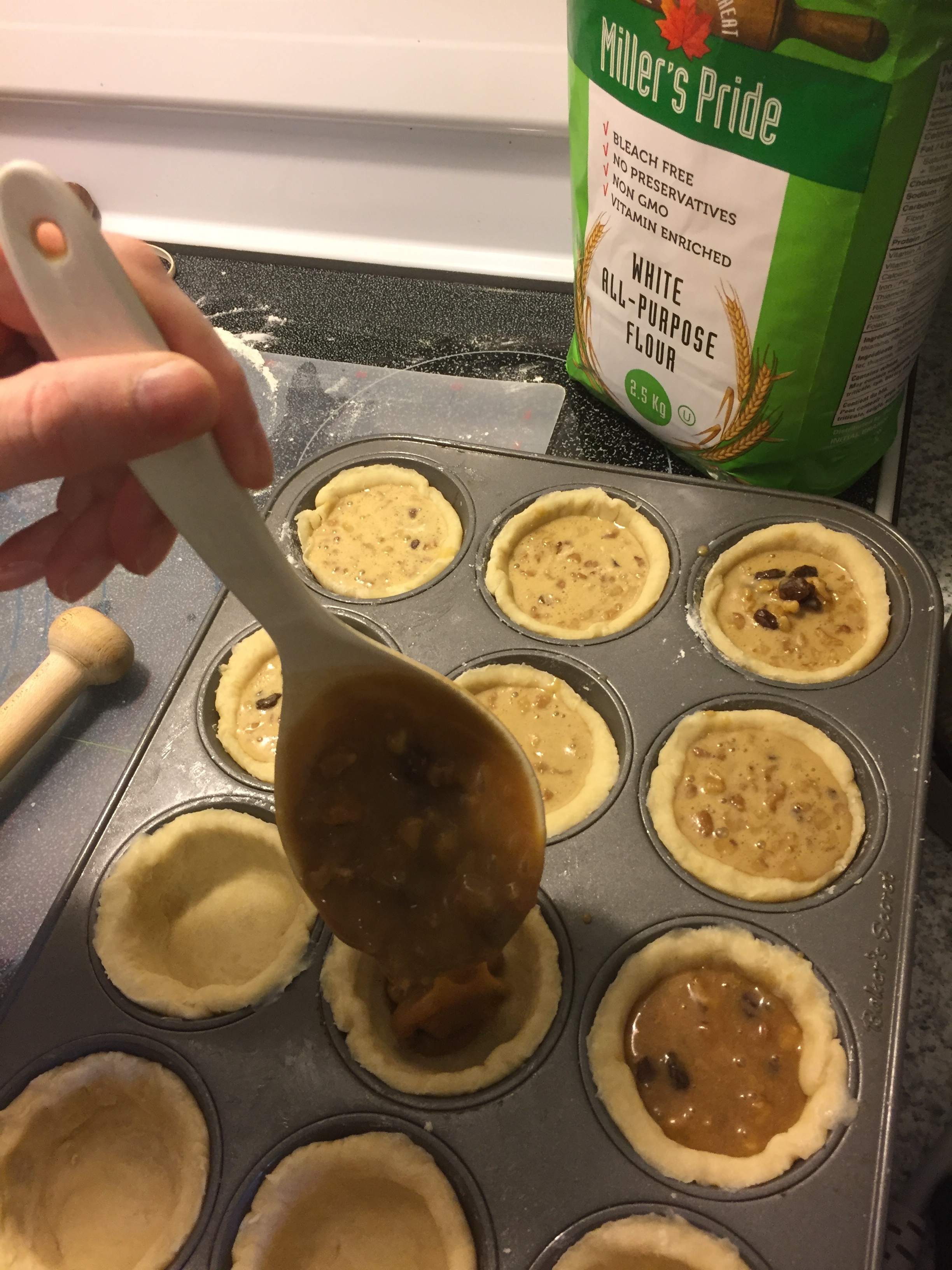

These tarts were a precious part of my childhood at family gatherings but contained many (to me) vile raisins that I would meticulously remove one by one, wiping my hands on my clothes. For my wedding in 2008, since I am not fond of cake and my husband adores my mother’s version, I asked my mother to make dozens of mini butter tarts for my guests. Some of the tarts were even made sans raisins just for me, making it easier to keep my dress free of the gooey filling. My stance on raisins has since softened. And if the trend of butter tart wedding cakes ever takes off, you know where it began.

This recipe is classic, unfussy, and consistent but with a slightly loopy script. It’s sweet, and it has that nothing-extraneous Scottishness about it that I rely on. It’s my mum in pastry form.

My mum, a retired nurse, mailed me the original recipe to use for this piece, but I also have the email she sent me years ago when she transcribed it. Her recipe for the pastry dough (pate brisee) isn’t written down because it’s burned into her memory, and is also used for her amazing apple pies and much-beloved tourtière.

Butter tarts have become big tourist draws. We have a Butter Tart Tour in the Kawarthas area near where my mum grew up, and a Butter Tart Trail near the city of Guelph. Ontario’s Best Butter Tart Festival and Contest is held in Midland, Ontario, annually. Whether you add raisins or not, walnuts or pecans, nobody can really agree. Maple bacon versions and some containing coconut are popular variations on the traditional. Since I am a purist, I prefer mine with walnuts since pecans are not native to Canada, and would not have been cheap or easy to find here 100 years ago.

Happy Canada Day!

Butter Tarts (yields 12 tarts)

Note: You can use your own pastry dough recipe or purchase pie crusts.

Ingredients

Pastry for 2 pie crusts

2 eggs

1 cup packed brown sugar

1 tsp vanilla

1 Tbsp white vinegar

½ cup melted butter

¾ cup raisins

¾ cup chopped walnuts

Directions

1. Set oven to 400 degrees F.

2. Grease 12 – 3” pie pans (muffin tins)

3. Roll pastry and place in pans

4. In a large bowl, beat eggs. Beat in brown sugar. Stir in vanilla and vinegar. Mix well and stir in melted butter. Fold in raisins and walnuts.

5. Spoon mixture into pans. Place pan on cookie sheet.

6. Bake for 10 minutes then reduce to 350 and bake for another 25-30 minutes. Let cool.