Anise Cookies • Anne James

Bretty Rawson

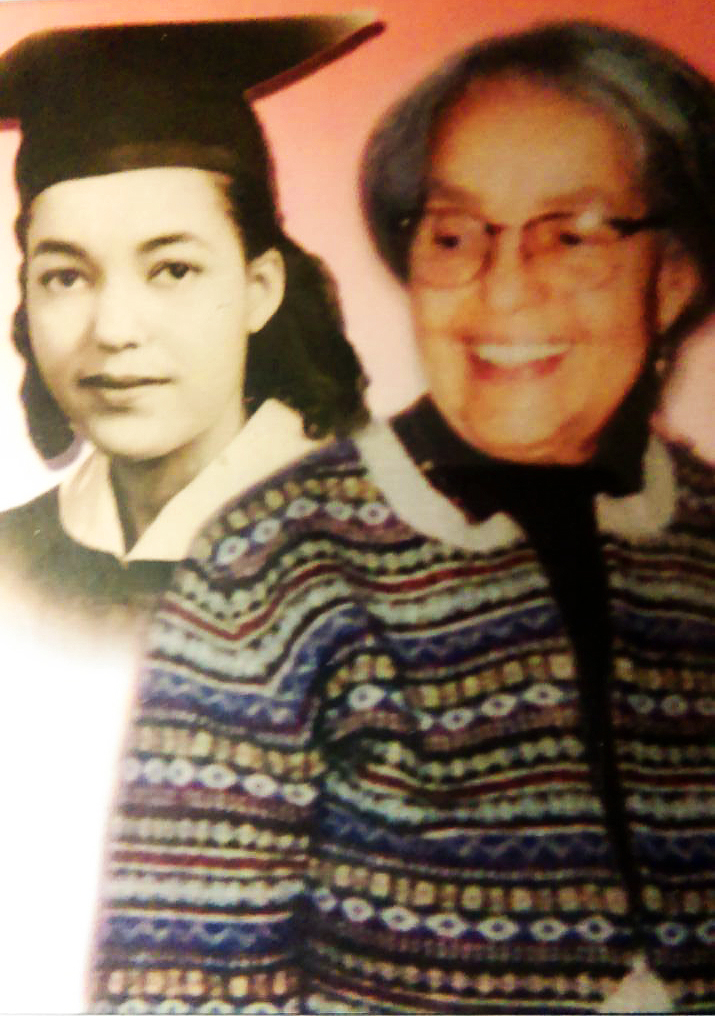

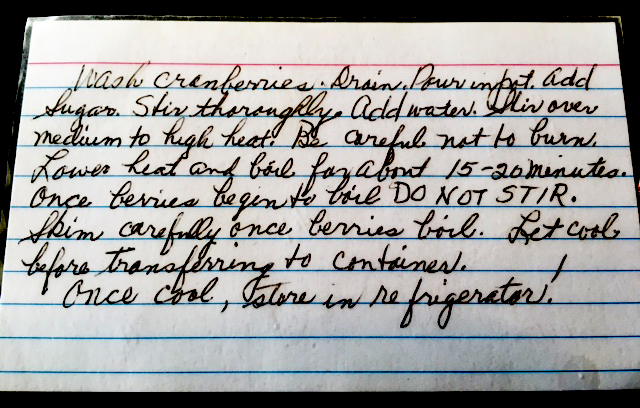

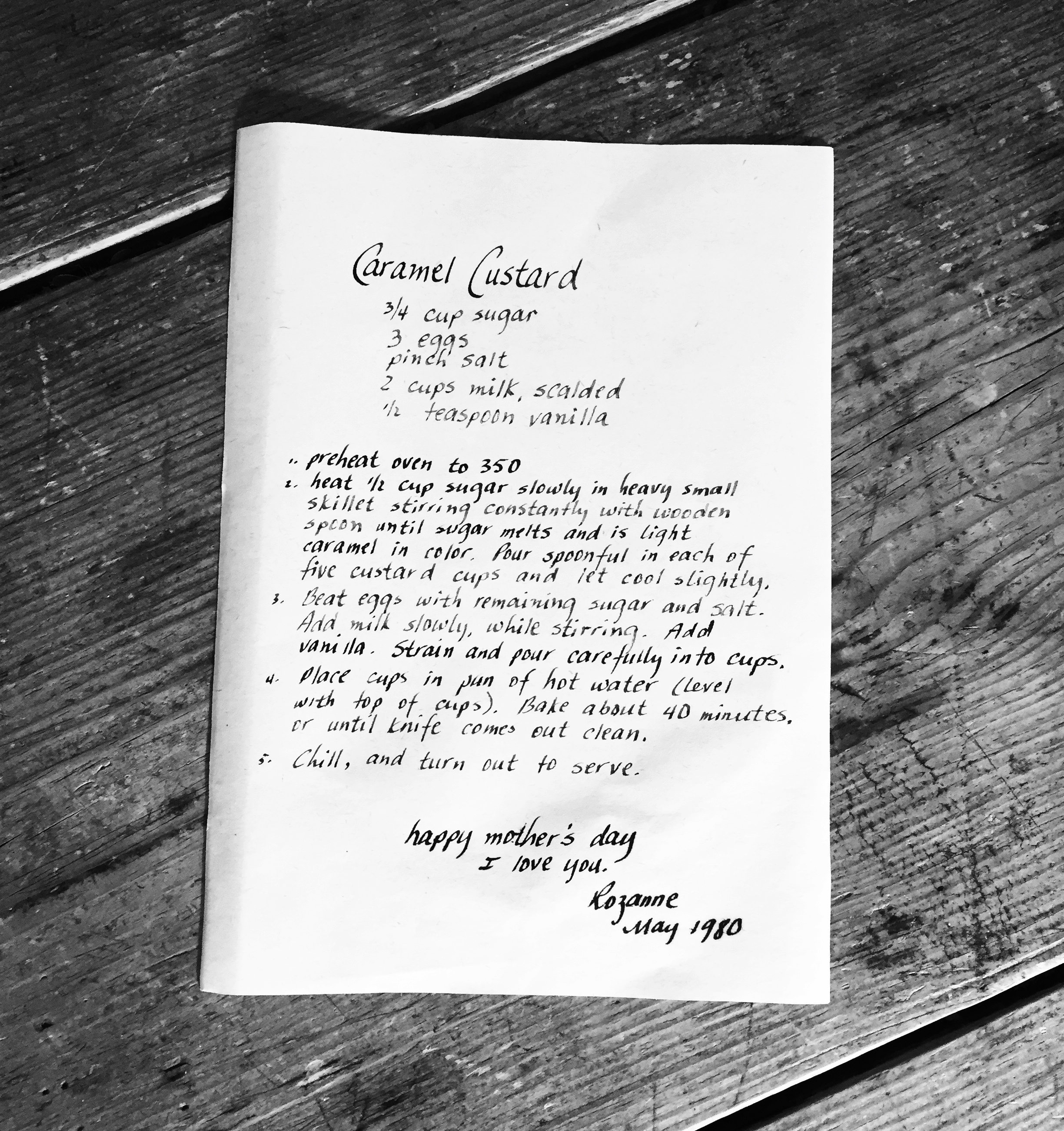

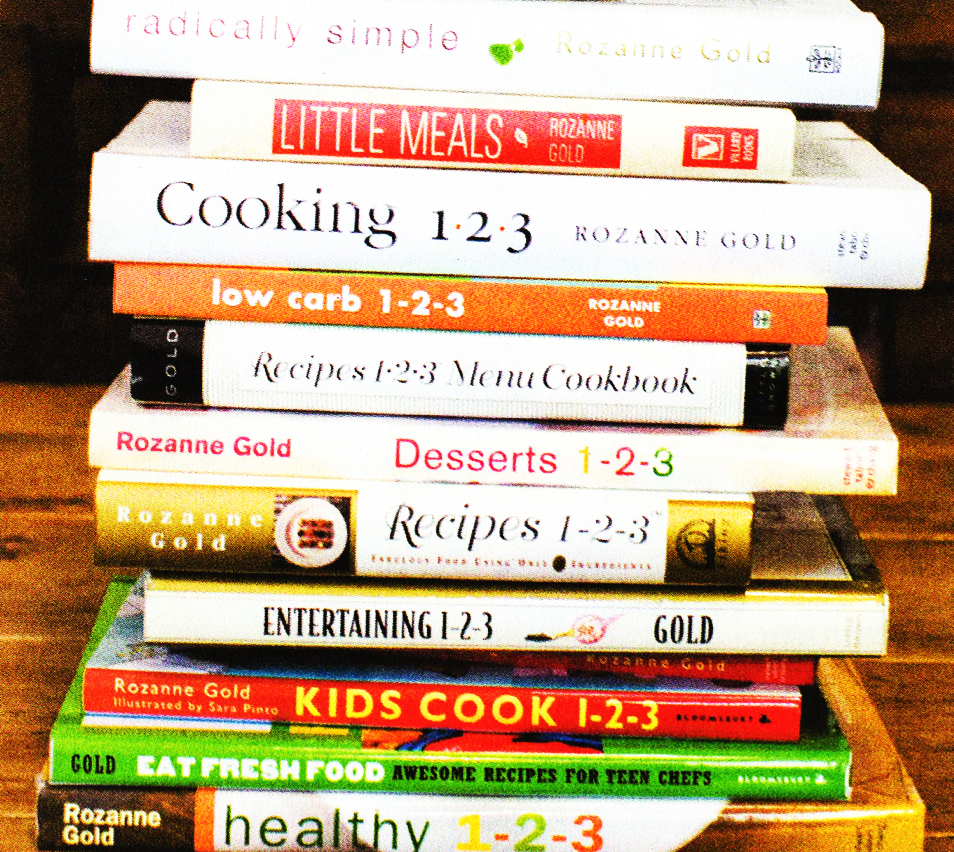

A note from curator Rozanne Gold: There are few more poignant daughter-and-father rituals than this evocative memory shared by Anne James, an Associate Professor of Voice and Movement in the Department of Theatre & Dance at California State University, Fullerton . Anne heard me on Heritage Radio on “A Taste of the Past,” a popular program hosted by culinary historian Linda Pelaccio. Afterward, Anne wrote, “I was so moved by your project that I wondered how I would go about contributing a handwritten recipe that my grandmother passed on to me?” That, of course, goes right to the essence of this column: The reawakening of memory through the swerves and curves of a penned recipe. And her writing is beautiful… “When he popped open the tin, the sweet, distinct aroma caught him off guard. My father looked at me, stunned. As he unfolded the tissue paper, he tossed back his…” We are grateful to have Anne’s original recipe and wonderful photos of the story’s compelling characters.

Anise Cookies by Anne James

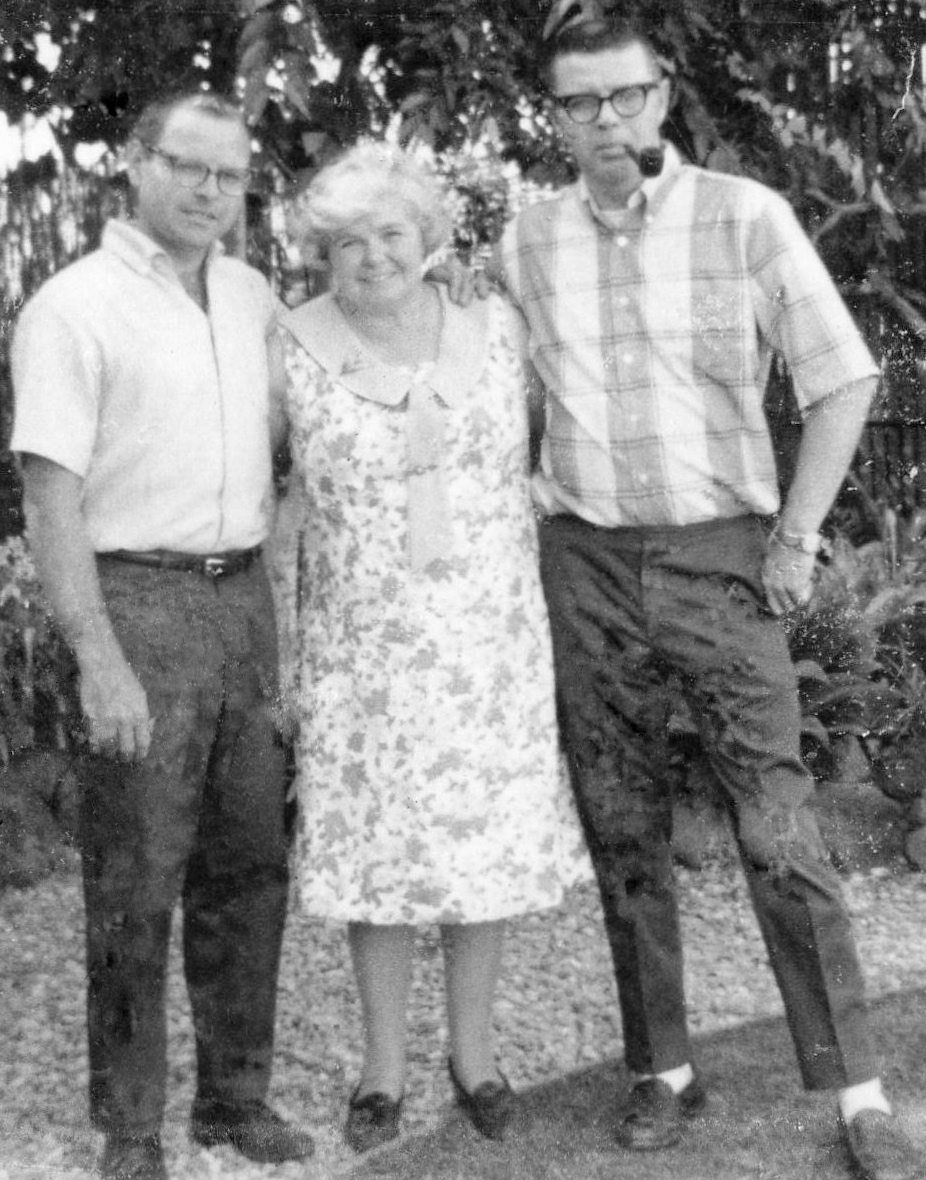

My beloved grandmother, Florence “Flo” James, was a good old-fashioned English cook. The knee-buckling aromatics of roasted potatoes, sage, and braised meat permeated every corner of my grandparent’s Yucaipa, California home. The upholstery smelled like pastry. Baking was her true love.

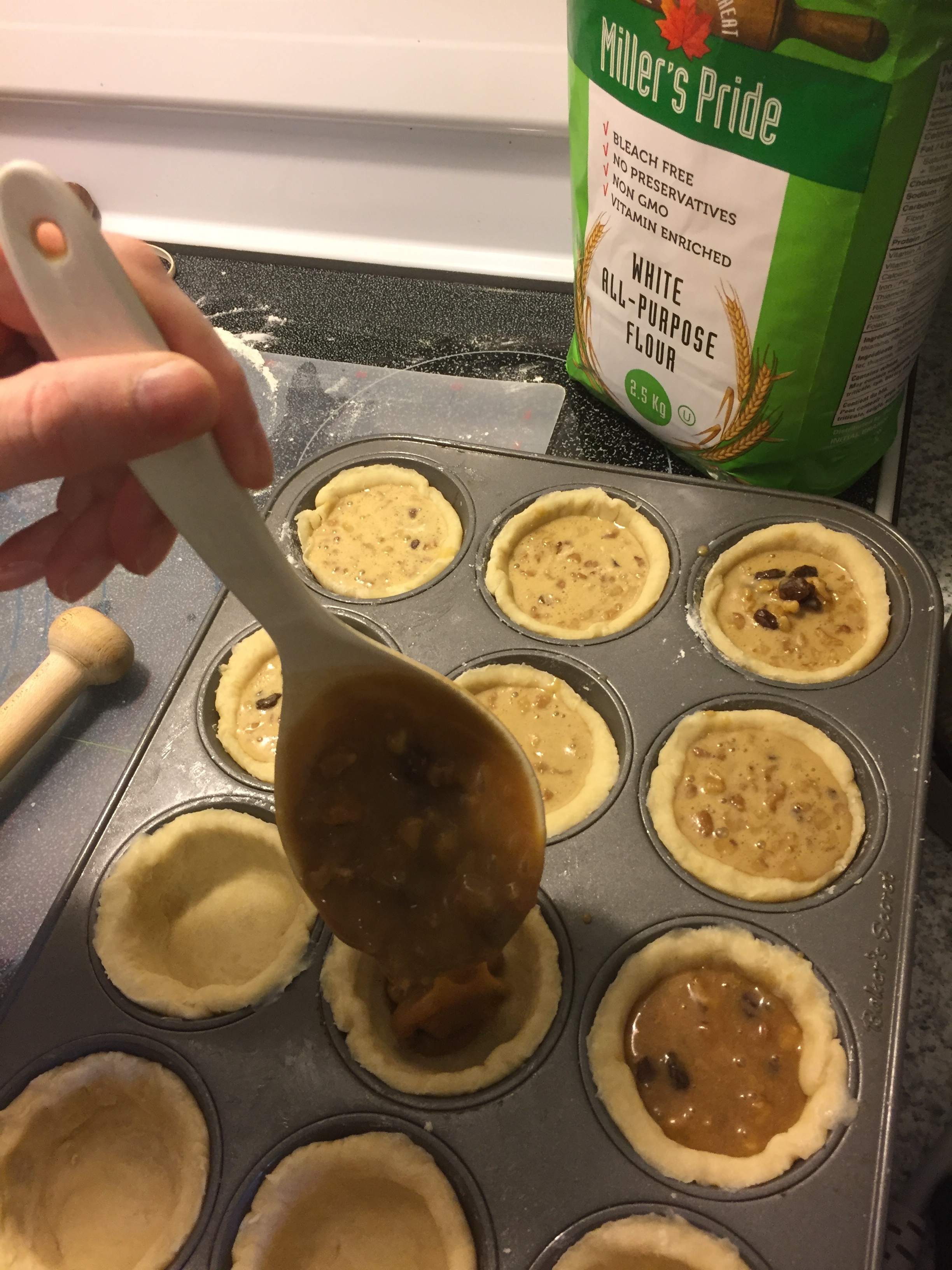

Flo was stout, with a fluff of white, curly hair and flushed cheeks, and resembled Mrs. Claus. Her cookie preparation for the holidays began as early as mid-October. Clad in her favorite pink gingham apron, she’d happily hand-beat batch after batch. By Christmas Day she would have plated over a dozen different delicacies: Ginger Snaps, Date Balls, Hazelnut Puffs, Walnut Stars, Coco Krispy Crunches, and Wedding Cakes (with her signature whole maraschino cherry tucked inside!). Don’t even get me started on her Fruit Cake.

And then there were her signature Anise Cookies. Flo baked these just for her son, George (my father). These particular sweets were a maternal gesture that began in the mid-1930s and stretched into my Dad’s adulthood. One whiff of their licorice scent transformed my father, an internationally renowned watercolorist and professor, into a giddy, little kid. Holding up a precious nugget as if to expose its facets to the light, he would annually rhapsodize on the elements of the perfect Anise Cookie; the separation of the milky white meringue from the caramelized, caked bottom; the bouquet released with each bite; their miraculous transformation as they aged into a delectable granite-like shard.

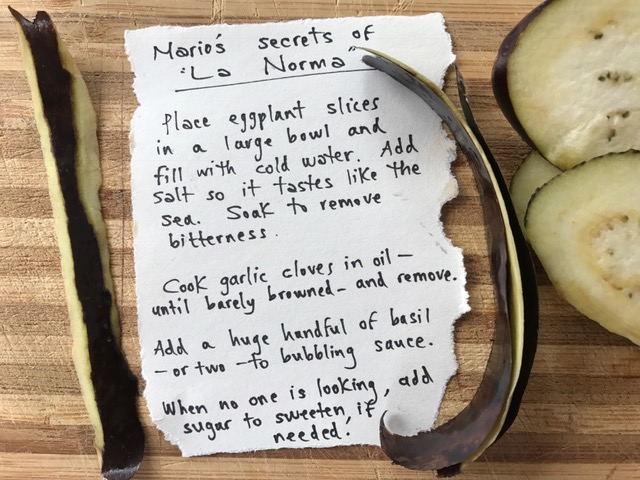

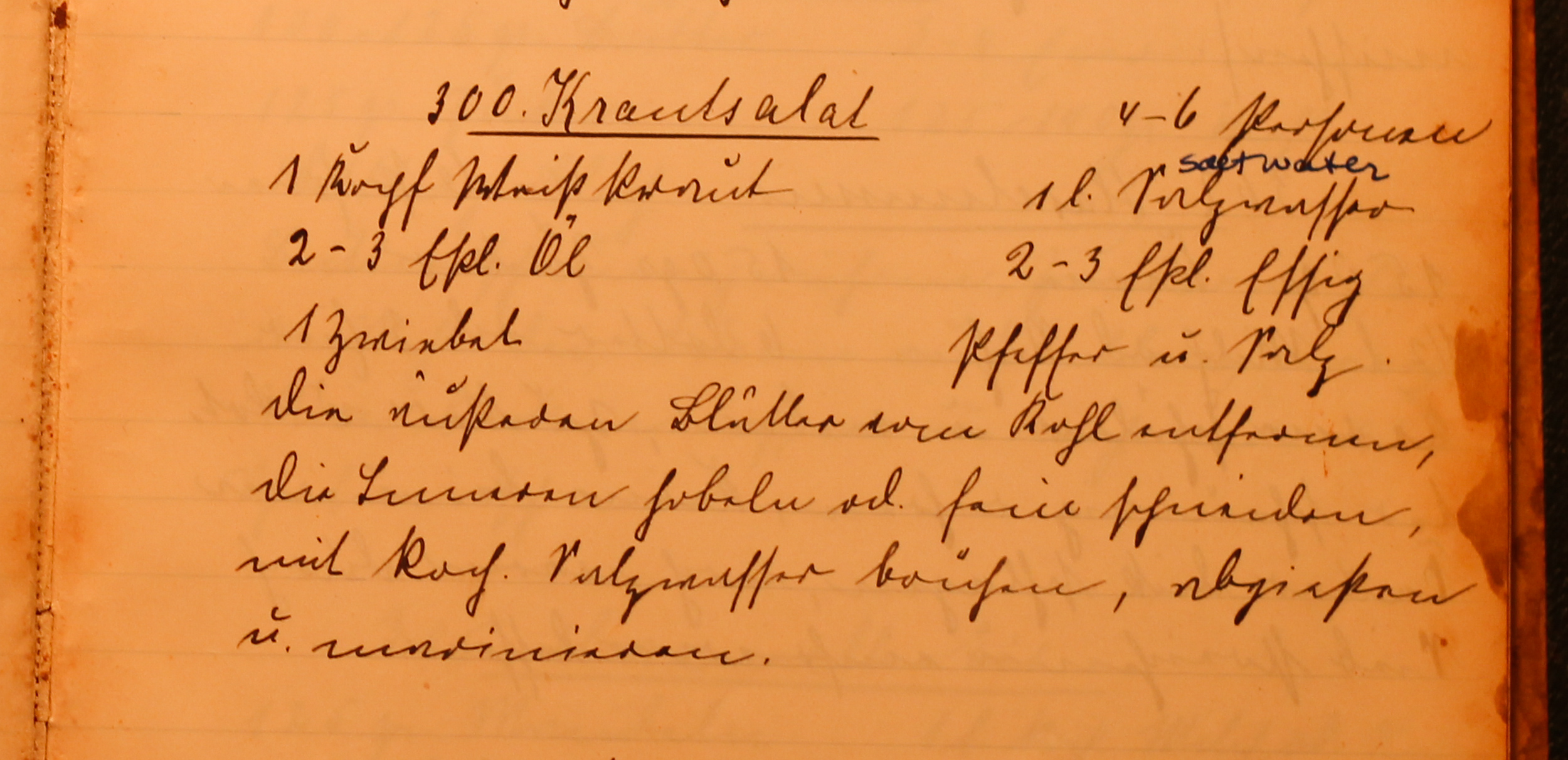

Often at my Grandma’s hip, I would be mesmerized while she prepared English staples; steak and kidney pie, Cornish pasties, Yorkshire pudding. She compiled her favorite recipes into a small, handwritten cookbook that she gifted to me, her only granddaughter. Thankfully, all of her cookie recipes were included. Then thirteen, I cradled the micro-tome in my hands, awed that she had entrusted me with her culinary secrets.

Grandma passed away in the late 1980s. Our family stumbled to fill the void left by our own Mrs. Claus. A decade later, as a graduate student crafting inexpensive Christmas gifts, I remembered the cookbook.

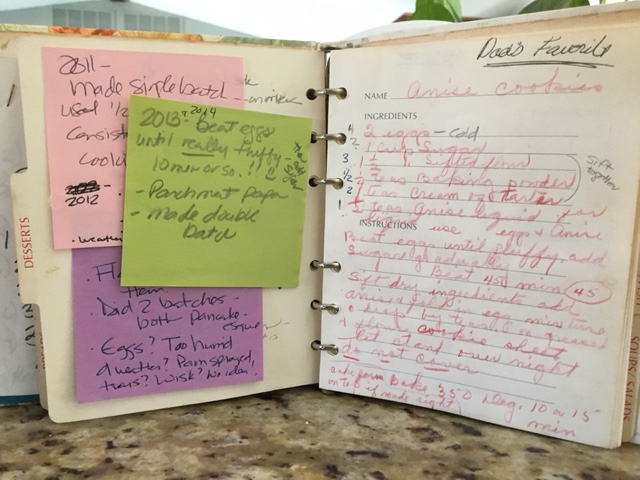

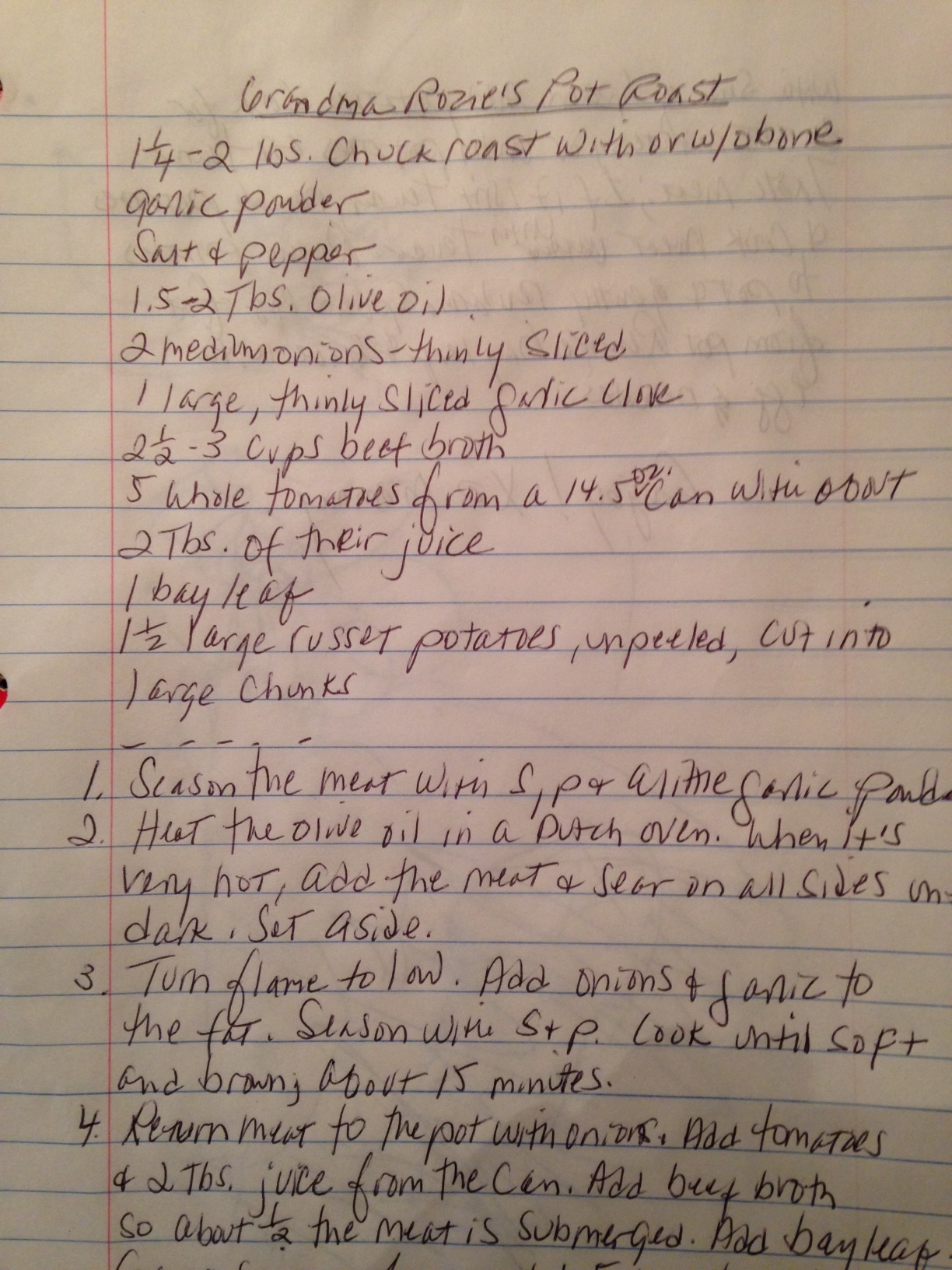

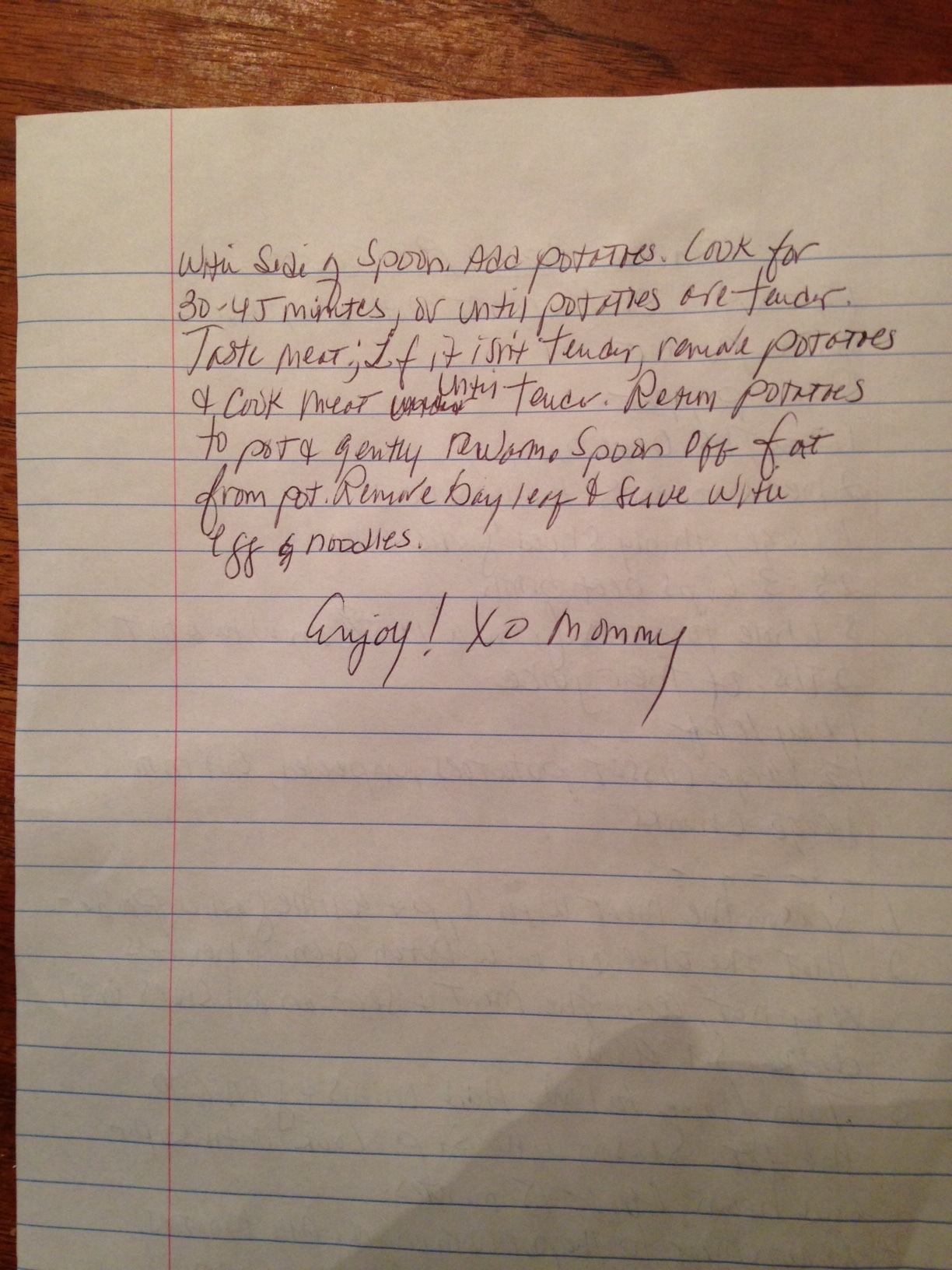

Flipping through the pages, there it was: her Anise Cookie recipe. The words, “Dad’s Favorite,” were carefully written in my teenage script at the top of the page. Grandma’s swirly, red-penciled handwriting talked me through it. Anise liquid was an exotic splurge. Beat the eggs “until fluffy for 45 minutes.” She mixed these by hand? “Let stand overnight”— I opted to chill them instead. That was my first handwritten contribution to her recipe.

Christmas morning, I presented my Dad with the tin. Though eye-ing his toddling granddaughter, he accepted it and distractedly popped open the lid. That sweet, distinctive scent escaped. His attention snapped back to the metal box.

He looked at me stunned.

Unfolding the tissue paper, he tossed back his head and let out a soft sob. Carefully, he picked up one of the creamy gems. He marveled at it for a moment and then took a bite.

With a deep exhale, he slowly chewed and grinned. The chaos of Christmas morning swirled on. But, there he sat, the open tin perched on his lap, blissfully transported: A son unexpectedly basking in the spirit of his mother.

I baked Anise Cookies for my Dad every Christmas after that. Before the mayhem of presents, I’d find a quiet moment to slip him his stash. It became one of our favorite father/daughter rituals. He’d pop a cookie into his mouth and hum with delight. We’d study that year’s batch, noting the subtle differences in texture, color, and fragrance. Then, he’d happily scurry away to hide his cookie booty.

I built on Grandma’s recipe, finessing her instructions with each pass; noting the impact of egg size, humidity, and parchment paper vs. aluminum foil. I tracked them, year by year, on attached Post-It notes. My last comment was dated December, 2014.

My Dad passed away in March of 2015. Though his appetite was diminished from years of chemotherapy treatments, he managed to nibble a cookie a day that final holiday season. It was a touchstone of a well-lived life; one that began simply enough, as a holiday treat baked by a young mother for her cherished first born and, unwittingly, setting into motion an unbroken streak that spanned over fifty years.

I didn't bake this last Christmas. It is still too painful. A well-meaning friend, however, knowing of our tradition, baked me a batch of my father’s beloved cookies. I graciously accepted, but waited until I was alone to open them.

One whiff of that licorice scent triggered a searing ache of grief. Too soon. Maybe next year.

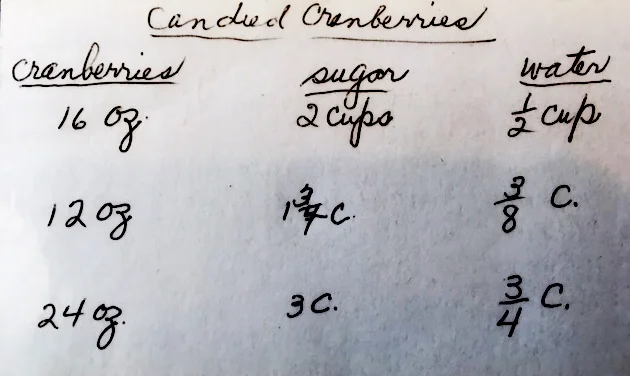

Florence James’ Anise Cookies

My notes are in italics – A.J.

2 eggs – cold

1 c. sugar

1 ½ cups of sifted flour (I used organic flour)

¼ t. cream of tartar (bought fresh every year – found made a significant difference)

½ t. Anise Extract (ordered yearly from Spice House in Chicago, IL)

(Sometimes I added a touch more. But not too much or else it makes the dough droopy)

Line cookie sheet with parchment paper. Beat eggs until fluffy. (Until really fluffy-at least 10 min or so). Add sugar gradually. Beat for 45 minutes.

Sift together flour, baking powder and cream of tartar. Fold into egg mixture. Drop by teaspoon onto a greased and floured cookie sheet (I used parchment paper). Dough will be sticky.

Let stand overnight – Do Not Cover (I chilled in my fridge overnight uncovered). Chill for at least 10-12 hours.

Bake at 350 degrees for 10-15 minutes. A cake forms on top if made right. I’d say the top is crunchy with a cake bottom. I used to make a double batch that my Dad would ration through January. But this is my Grandma’s original recipe. These measurements make about a dozen