My Mom’s Bread Pudding • Rosie Nelson

Bretty Rawson

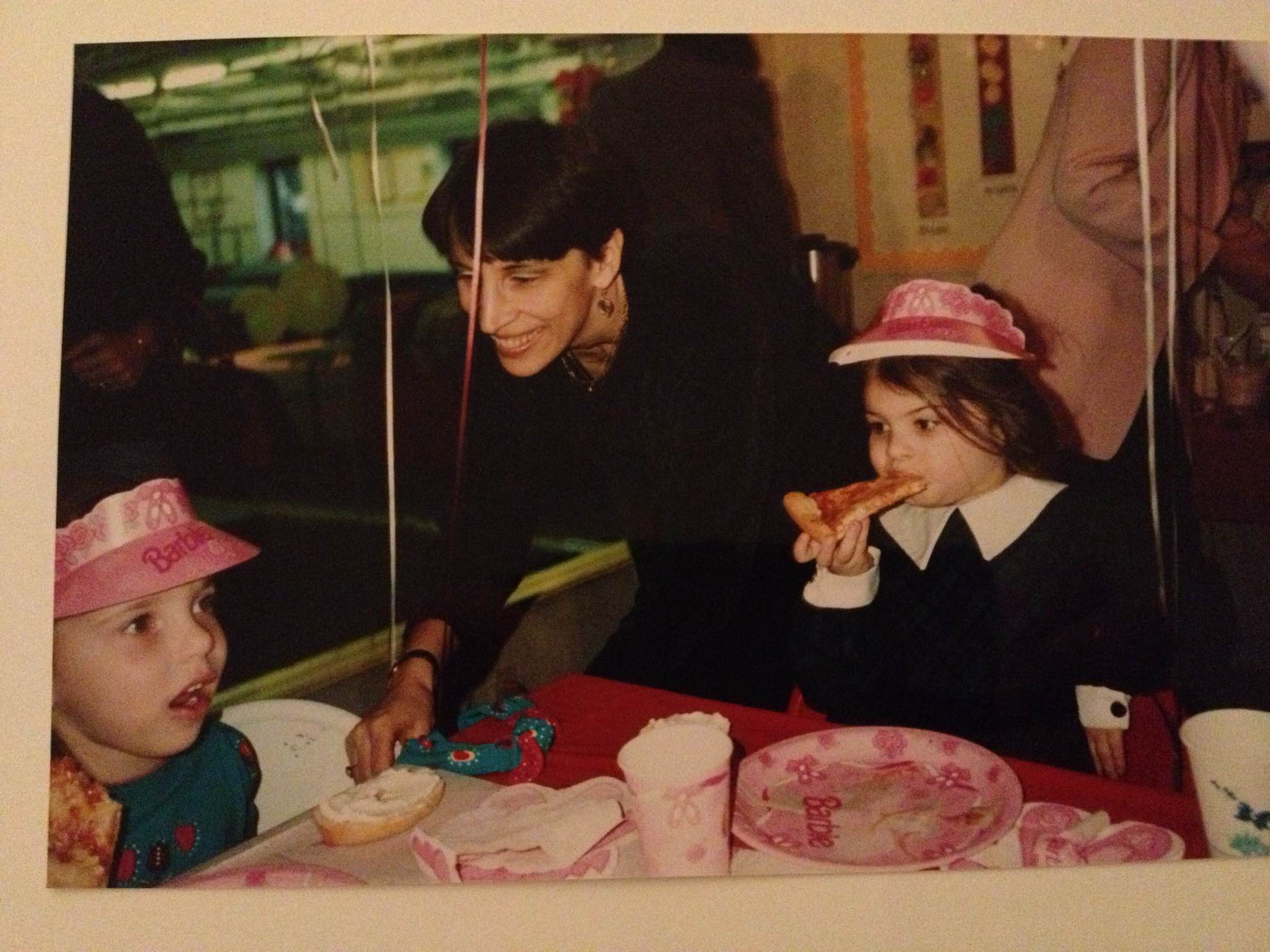

Note from curator Rozanne Gold: What a charming story from Rosie Nelson, who shares with us not only a delicious recipe, but a delightful, warm, and unexpected peek into a family holiday. And what a family it is. Her mother, Dr. Judy Nelson is Chief of Palliative Care at Memorial Sloan-Kettering in NY, her dad Eric is a crackerjack lawyer, and Rosie, a recent college grad, is an advertising exec, with an exuberant passion for food and…bread pudding. You’ll find out why, here. Thank you, Rosie. (p.s. Rosie was one of the teen sous-chefs who helped test recipes and had a starring role in my book “Eat Fresh Food: Awesome Recipes for Teen Chefs, Bloomsbury, 2009.)

My Mom's Bread Pudding by Rosie Nelson

I was about ten years old, I came home the day before Passover (a holiday where one eats matzoh) only to find a gigantic homemade bread pudding sitting in the kitchen.

Having a few years of Hebrew school under my belt, if I had learned anything about Judaism, it was that we do not eat leavened bread during the eight day-period that Passover is celebrated. Why then had my mom, who had spent many more Passovers than my ten, listening to her father (my grandpa) retell the story of the Jews’ hasty exodus from Egypt, put together this soon-to-be forbidden pudding that we would no longer be able to enjoy?

My mother, a renowned doctor, had a logical response: She didn't want the three loaves of bread remaining in the kitchen to go to waste. So she made bread pudding; and the three of us enjoyed a warm delicious dessert that night. Naturally, the majority of the pudding was left in the dish, staring at me every time I walked into the kitchen. What could I do but take another bite? Was that a bit of Grand Marnier, I tasted? The texture was so creamy. The raisins were so plump and sweet. The holiday had begun, the pudding now off-limits, and I remained taunted by my mother’s great baking skills. Restraint is not one of my virtues. How sad to have that gorgeous pudding go to waste. But as the bread pudding sat-in-state as the holiday progressed, the only choice was to throw it away! My mom's seemingly logical plan to avoid being wasteful no longer seemed as logical — now that along with the bread, the milk, spices, sugar, eggs, and raisins now also had to be trashed, not to mention the hour of work she spent making it.

As a ten-year-old, little did I know that bread pudding would create lifelong memories of holidays past, family gatherings, thrifty meals and, unpredictably, of Buenos Aires, where I spent six months studying during a semester of college. To say that food and cuisine were central aspects of Argentine culture is an understatement. My wonderful host mother, Monica, made countless memorable meals over which we discussed everything — from politics to art to cooking. I loved the experience so much that, one year later, I returned with my friend Shanen and stayed for a month.

On our first night, Shanen and I walked the local streets to a steakhouse, where we found ourselves five more times during our stay. After a huge meal, the panqueques con dulce de leche (crepes filled with dulce de leche) caught Shanen’s eye while the Budín (bread pudding), caught mine. We polished off all of it, only to find out that the bread pudding was a portion meant for four! But we ordered it again, and again.

I think of bread pudding every Spring, the time of year when Jews all over the world share a traditional Seder meal. But I think of my mother every time I see bread pudding on a restaurant menu. It is now fifteen years since the Passover bread pudding story began but I know the memory of the forbidden dessert will make the holiday seem a little bit sweeter next year.

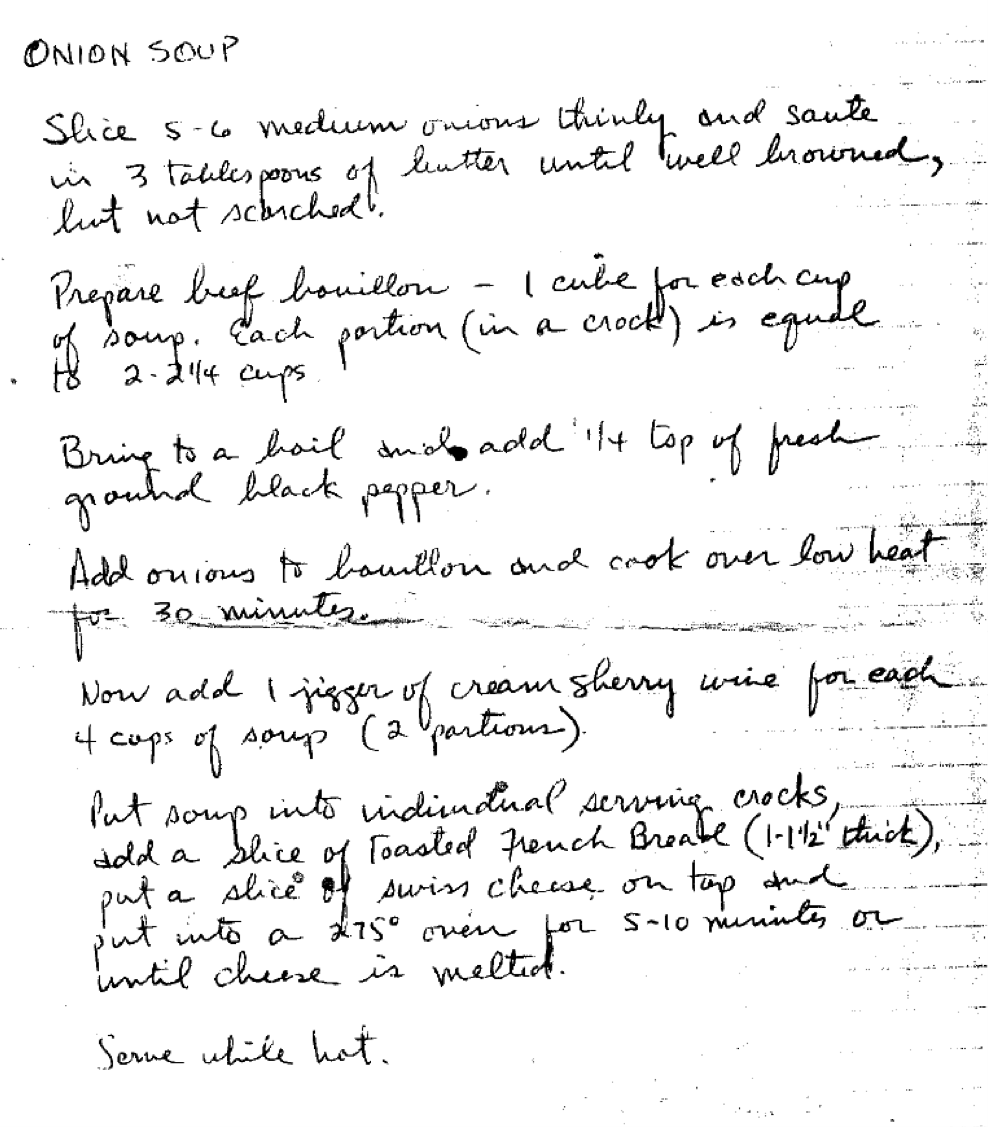

The recipe is written in my mother’s handwriting. Sometimes we make it with fresh blueberries, and sometimes we make it with chocolate chips. And sometimes we bake it as is (and not in a water bath).

My Mom’s Bread Pudding

Serves 8

Butter for greasing pan

4 - 5 cups stale white bread cubes

¾ cup raisins

4 large eggs

¾ cup sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla

1 teaspoon Grand Marnier

1 teaspoon ground cinnamon

½ teaspoon freshly-grated nutmeg

½ teaspoon salt

3 cups milk

Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

1. Spread the bread cubes in a buttered 2-quart baking dish. Scatter raisins (or blueberries or chocolate chips) over the bread.

2. Thoroughly whisk together: eggs, sugar, vanilla, Grand Marnier, cinnamon, nutmeg and salt. Whisk in milk.

3. Pour the liquid mxture over the bread and let stand 30 minutes, periodically pressing bread down with spatula for absorption. Please dish in a water bath (fill pan about ½ up sides of the dish – use scalding hot tap water.) Bake until puffy and firm in the center – about 1-1/4 hours. Serve warm, room temperature or cold.

Note by RG: Although Rosie’s story is related to Passover, the bread pudding recipe is wonderful all year long. Top with fresh blueberries or peaches in summer; ripe pears in the fall, or bittersweet chocolate, any time.