ALLISON RADECKI: Since the first handwritten recipe profiled in this column was one that you penned and framed as a gift to your own mother, Marion Gold, for Mother’s Day in 1980, it seems fitting that we feature one of her own recipes today. Which handwritten recipe of your mother’s were you drawn to as you approached this holiday weekend?

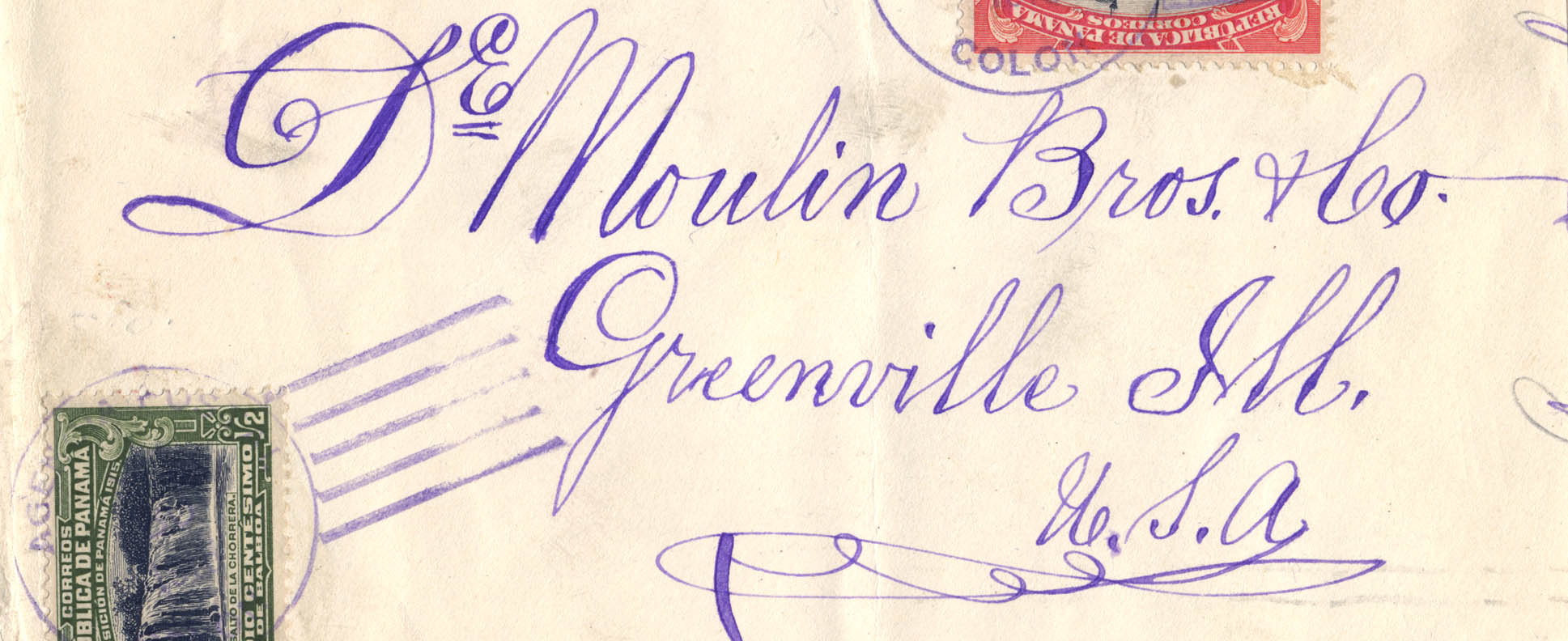

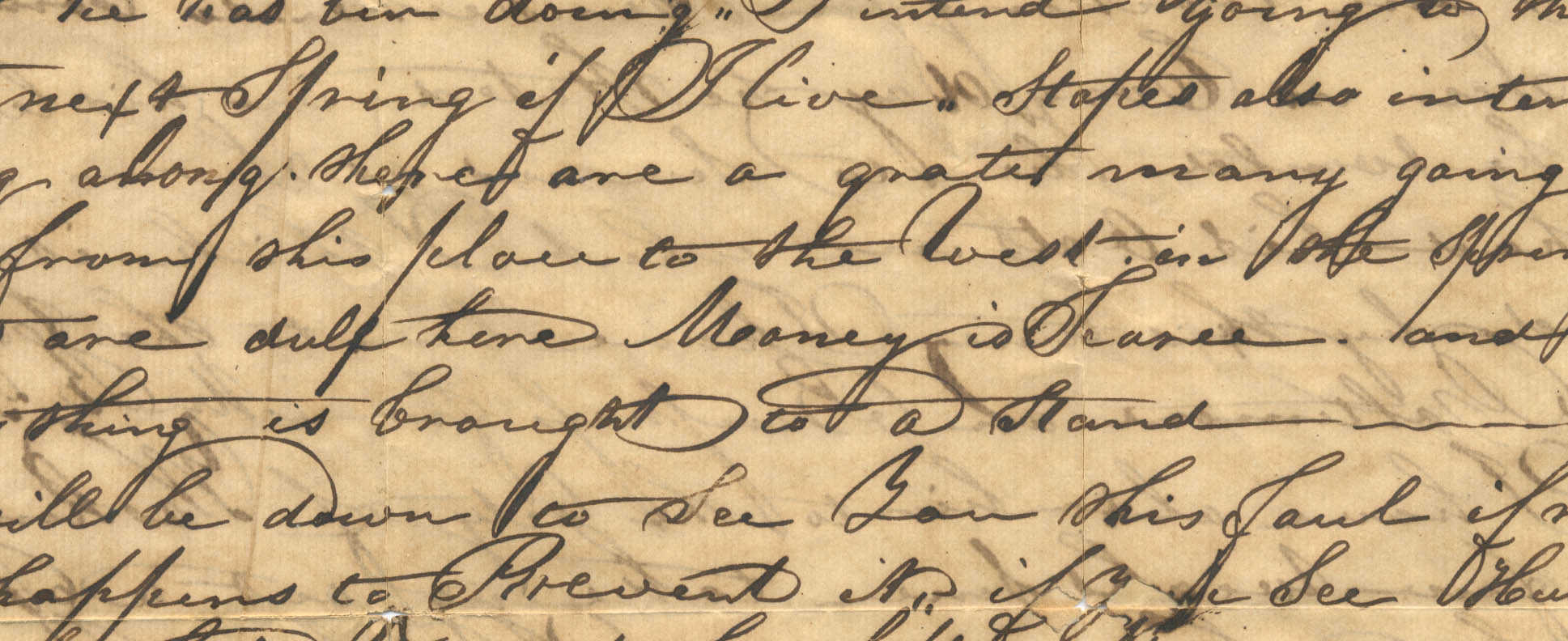

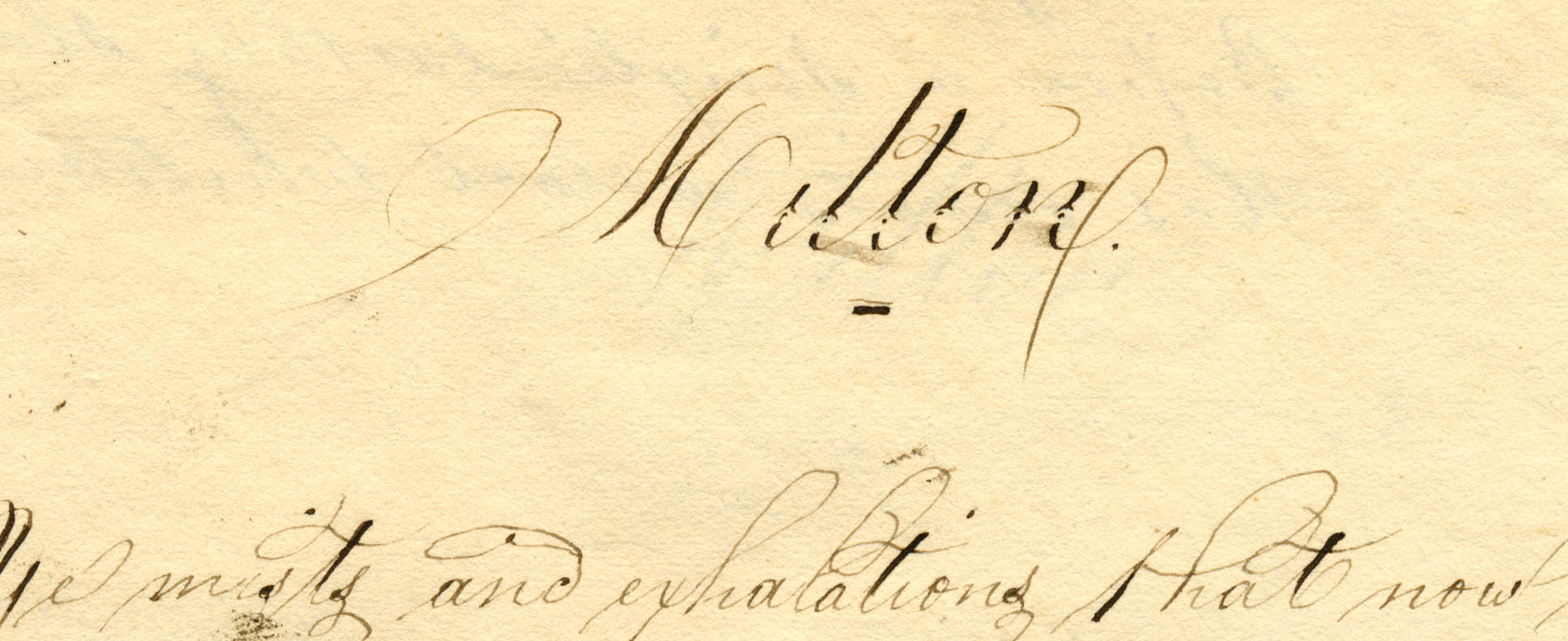

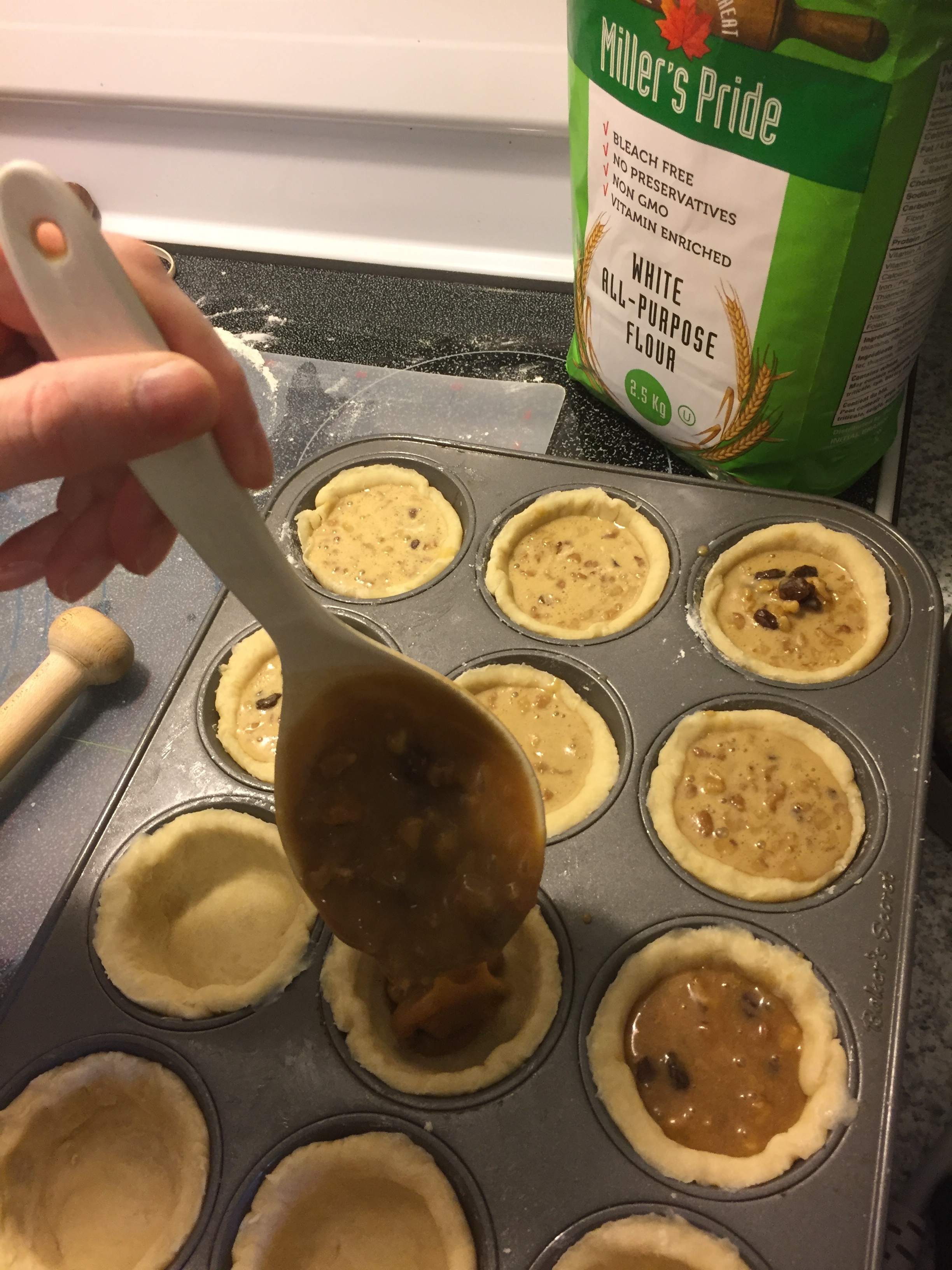

ROZANNE GOLD: I have a recipe for my mother’s Garlic Broiled Shrimp — with a debatable “s” at the end. She really never said “shrimps,” but she might have questioned herself while writing the title. Her handwriting is as elegant and finum (a Hungarian word for refined that she often used) as she was.

I was excited about the clarity and straightforward simplicity of this dish. Although I never follow a recipe — ever — I followed this one with great results. Michael (my husband) and I ate the whole thing standing up at the counter and were almost giddy from its clean, pure flavors, its stunning plainness. The second time I made it, I embellished a bit — a bit of tarragon and a splash of wine — and ruined it.

That day, with great intention, I summoned her up so that I could see her standing in her kitchen in Queens. There was a smile at the edge of her lips, her shoulders gently sloping, like the curve of her “m” in minced. She minced fresh garlic with her small, favorite knife that was never sharp enough. Would she peel and de-vein the shrimp? I imagine her long piano fingers delicately removing the black vein along the curve of each shrimp’s back. And there was all that curly parsley, meant to be finely chopped. I mean, curly parsley! When was the last time I bought curly parsley? This was a dish for company meant to be served with rice. A box of Carolina Rice was as iconic to me as a Warhol soup can.

RADECKI: Where did your Mom keep her recipes? And where do you now keep hers?

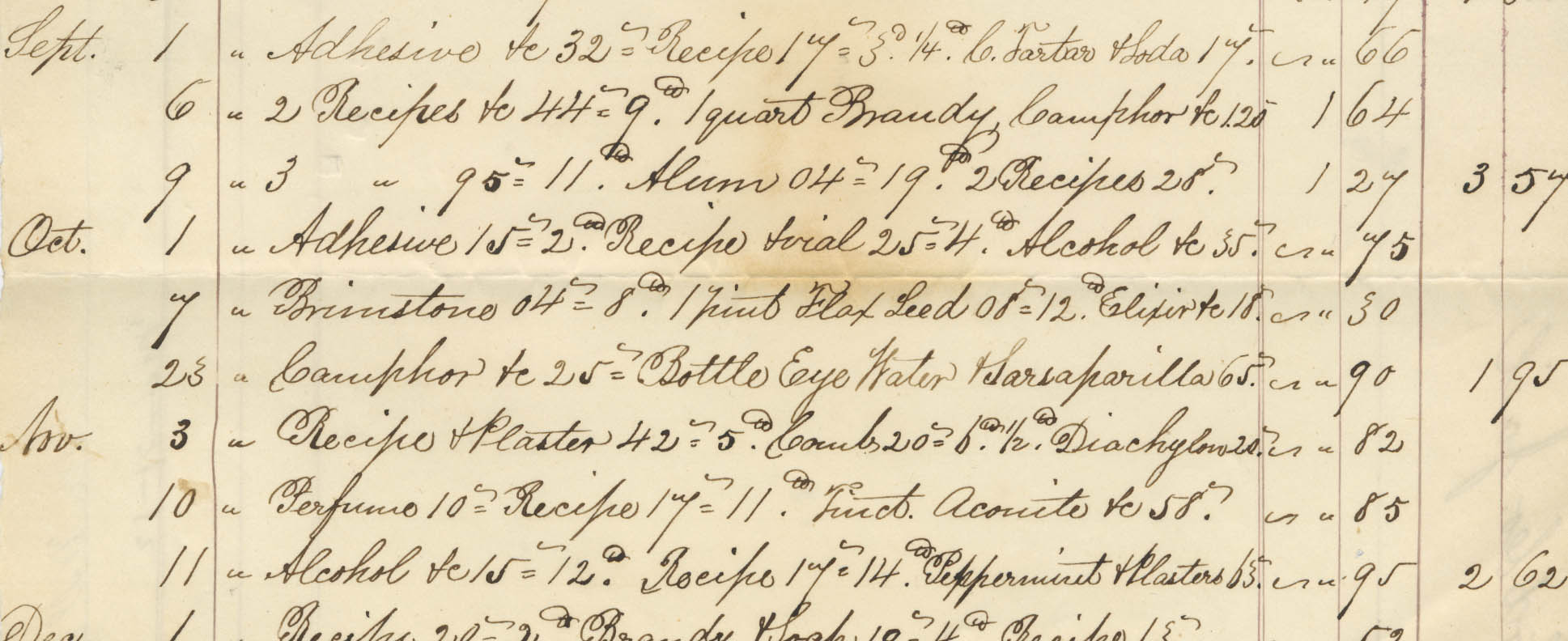

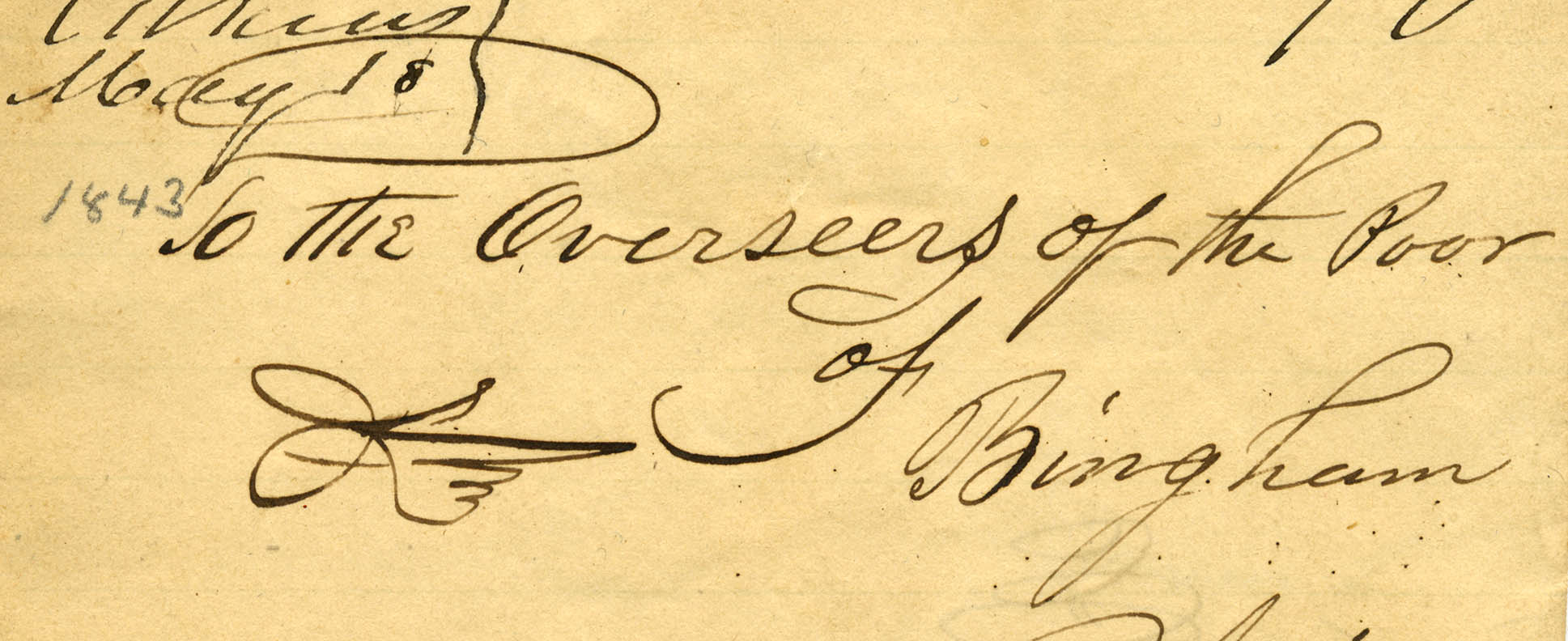

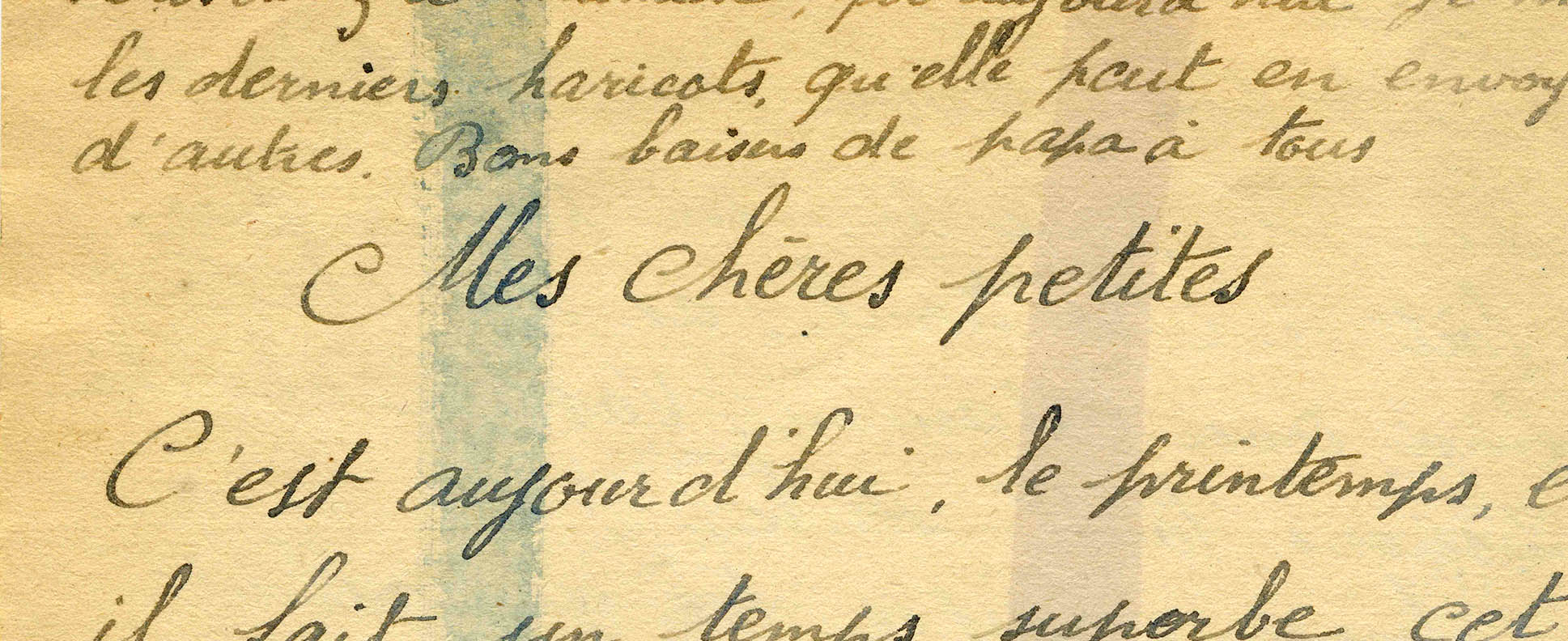

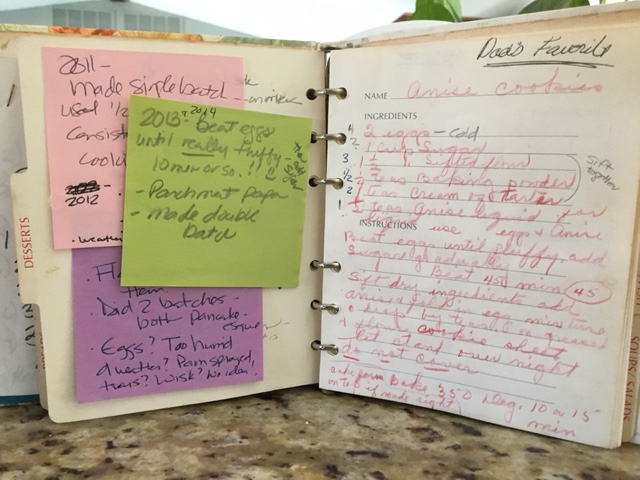

GOLD: My mother kept her recipes in a blue kitchen binder decorated with simple and colorful illustrations of kitchen utensils and ingredients. It has large yellow envelopes as dividers in which you could stuff too many recipe cards. After she died, I found a stash of additional recipes in an old-fashioned tin, filled with blue-lined index cards all in her graceful handwriting festooned with her beautiful swoops and swishes: chicken cutlets, fresh string beans, sour cream coffee cake. The binder and tin now nestle together in the drawer of my pine kitchen table.

RADECKI: Did your mom like to cook? Did she cook often? What do you remember about her cooking?

GOLD: Every night. She cooked every night and made the things we loved. Cabbage and noodles, another dish of stunning simplicity, was my comfort food growing up. Mornings were made special with her apricot-filled ultra-thin crepes called palascintas; meatloaf was always in the shape of a heart.

My mother also made something she called “Tunk-a-lee,” soft scrambled eggs with tomato, pepper, and onion — very Hungarian flavors — but every culture seems to have a version. Another dish I loved was a stew of hot dogs, cut on the bias, with potatoes and onions in a ketchup-y broth. And pot roast. She made the most fabulous pot roast with so many onions, a bay leaf, and splash of dry vermouth. She made it all the time and later revealed that she hated pot roast.

My mother loved to entertain. She’d take white bread, cut the crusts off, and roll it paper-thin with a rolling pin — so thin, it became like pastry. She’d then cover each slice with creamy blue cheese spread and put a fat canned asparagus on it. They would get rolled up tight, brushed with melted butter, and baked. Oh, how many of these I used to eat before company came! Lethal.

RADECKI: How would you describe your relationship with your mother?

GOLD: Ours was an amazing love story. It would be impossible to describe all the joys in our life together, but there was lots of sadness and loss, turmoil and drama, too. But there was also lots of happiness that we shared in big and small ways. I liked the small ways best. Laughing until we cried, playing scrabble; cooking, doing things to please or surprise each other, or just talking ten times a day on the phone. There were trips and travels and innumerable nights of splendor at The Rainbow Room and Windows on the World. There were victories and milestones to celebrate. And I got a chance to write about her in many of my books and magazine articles, too. She was modest and never believed in "tooting her own horn,” and told me never to toot my own. But, nothing came close just to being together.

RADECKI: You have often said that your mother was “More Zsa Zsa than Julia.” Can you paint a picture of the mom you see in your mind’s eye?

GOLD: My mother was a seeker of wisdom and beauty. She was such a beautiful woman. She loved people. She loved children. It always felt like she was doing something special, wanting to please.

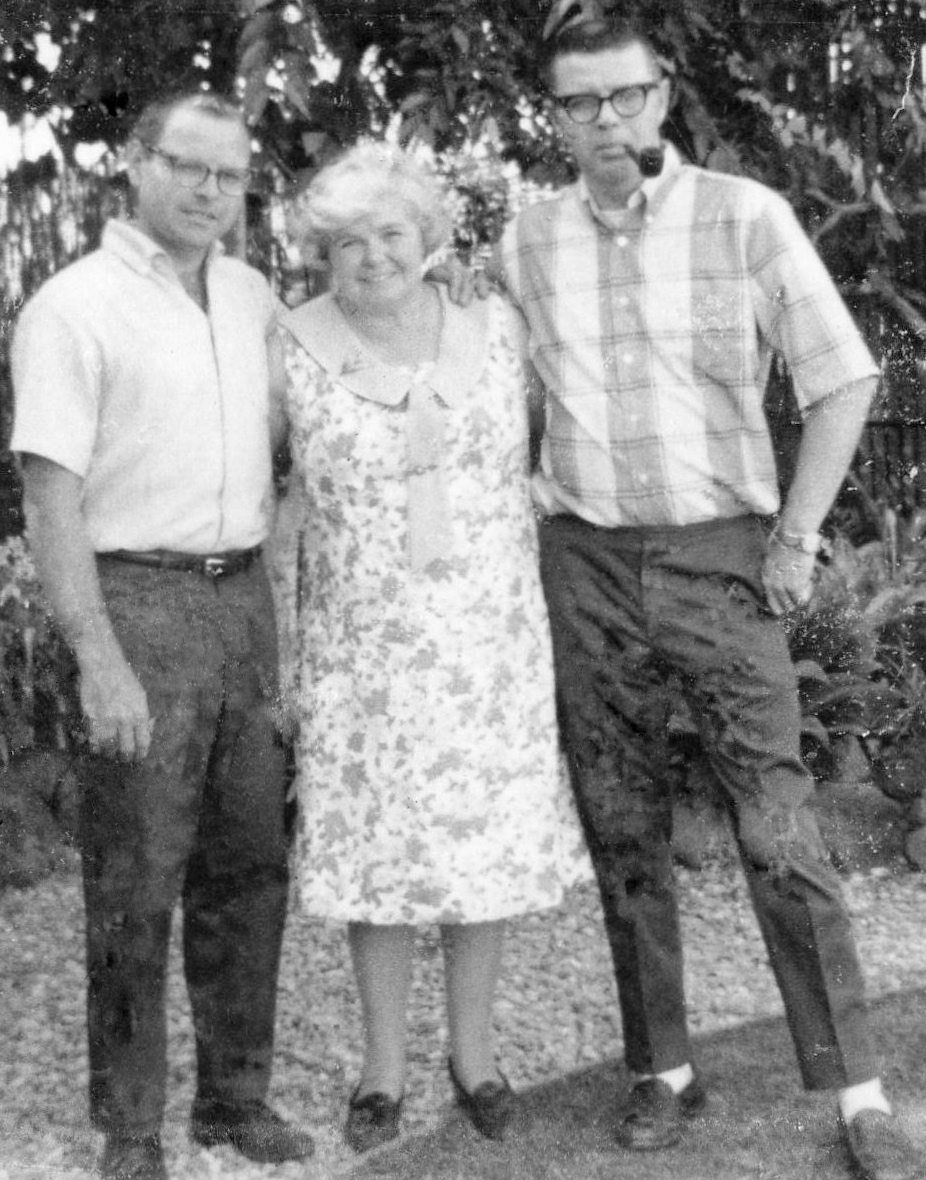

She grew up in Florida in a tiny town called Belle Glade, near Pahokee. It was just her, her mom, and her dad. They were poor, but she didn’t know it. She grew up happy. She was always a tall drink of water, though her bosomy mother was only four foot ten.

Mom escaped to the University of Miami, back when it was just one building. Her parents died in her early thirties within six weeks of each other. My mother told me that when her mother died, she felt as though her heart had broken. She carried a lot of sadness. There were deep feelings.

She was a teacher, a hospital volunteer and a medical assistant, but I think she wanted to be an actress. She could be the most glamorous person; a bit like Zsa Zsa.

On her 80th birthday, three weeks before she died, it took her quite a while to get ready. We weren’t going anywhere but she wanted to make it a special occasion. She was so weak but spent hours in her bedroom getting ready. When she finally came out, there were high heels, a mink jacket, and sequined glasses. She could hardly breathe, but she dressed up like a movie star. This is how she wanted us to remember her.

RADECKI: You and I often talk about how recipes — especially handwritten ones — ignite connections. In the spirit of sparking a memory or two, let’s play a quick game. Tell me the first thing that comes to mind about your mother when I say:

Scent: Onions and her own sweet perfume. We each had our own scent. I wore Rive Gauche. She was a sexy, sensual woman.

Sight: It’s summertime, and she’s in the backyard drinking an iced cold Heineken. It’s so out of character, but that’s what I see.

Sayings: "Kickups." If I acted out, she would say, "kickups." As in, "Watch out. You’re about to head into trouble."

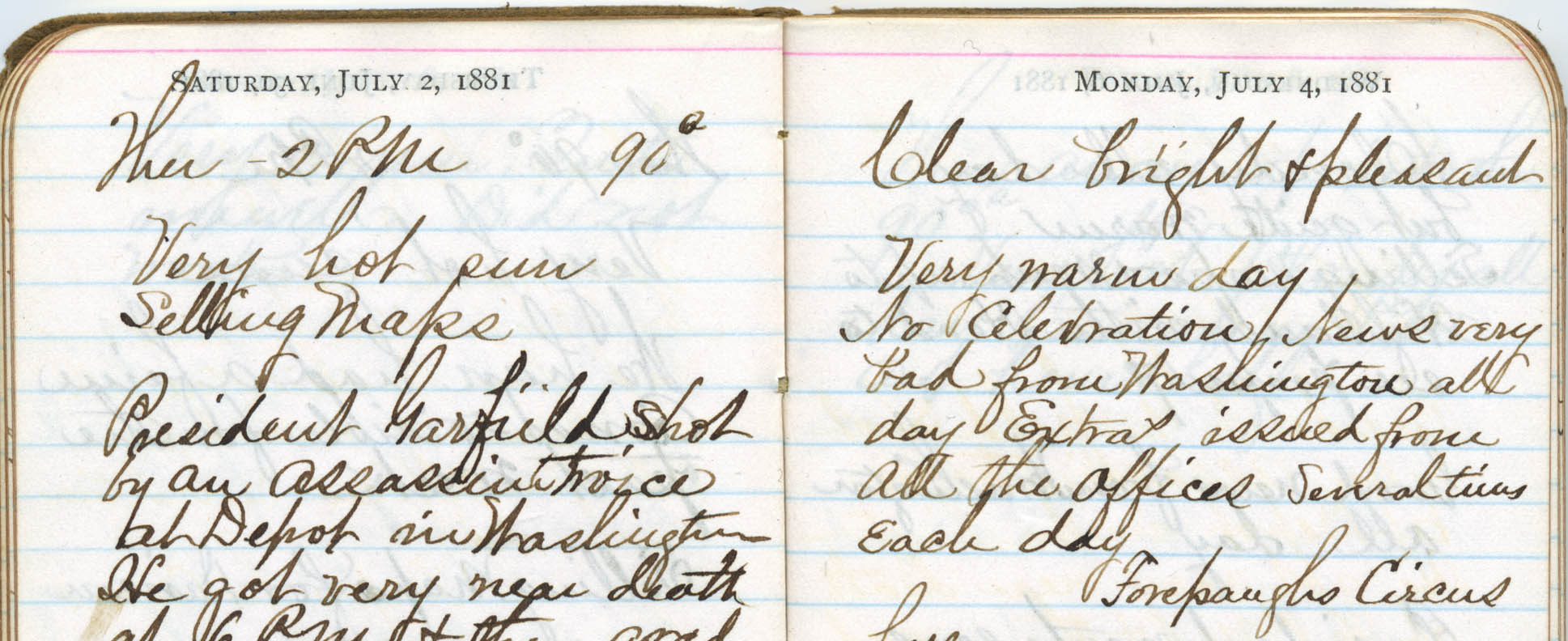

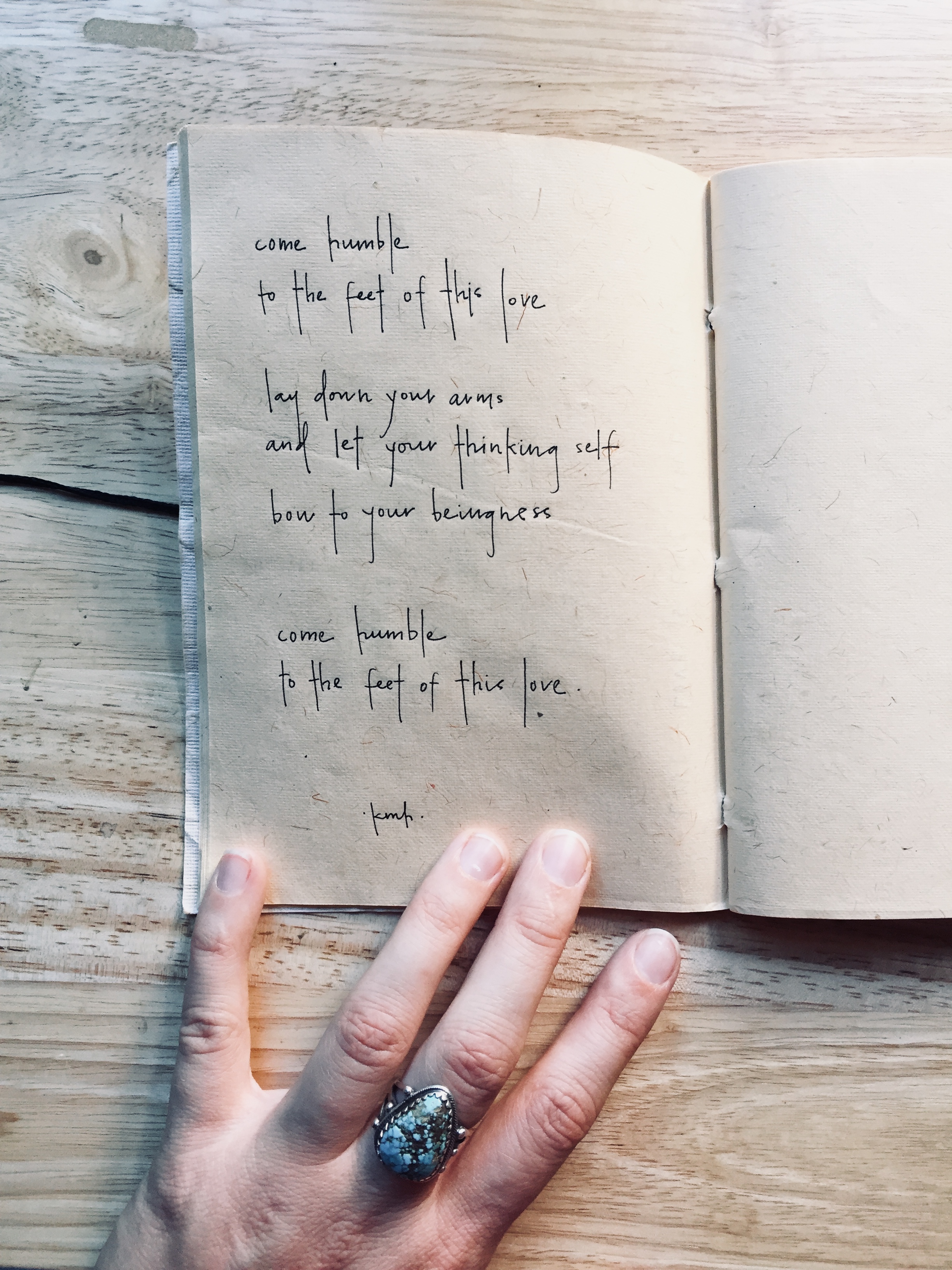

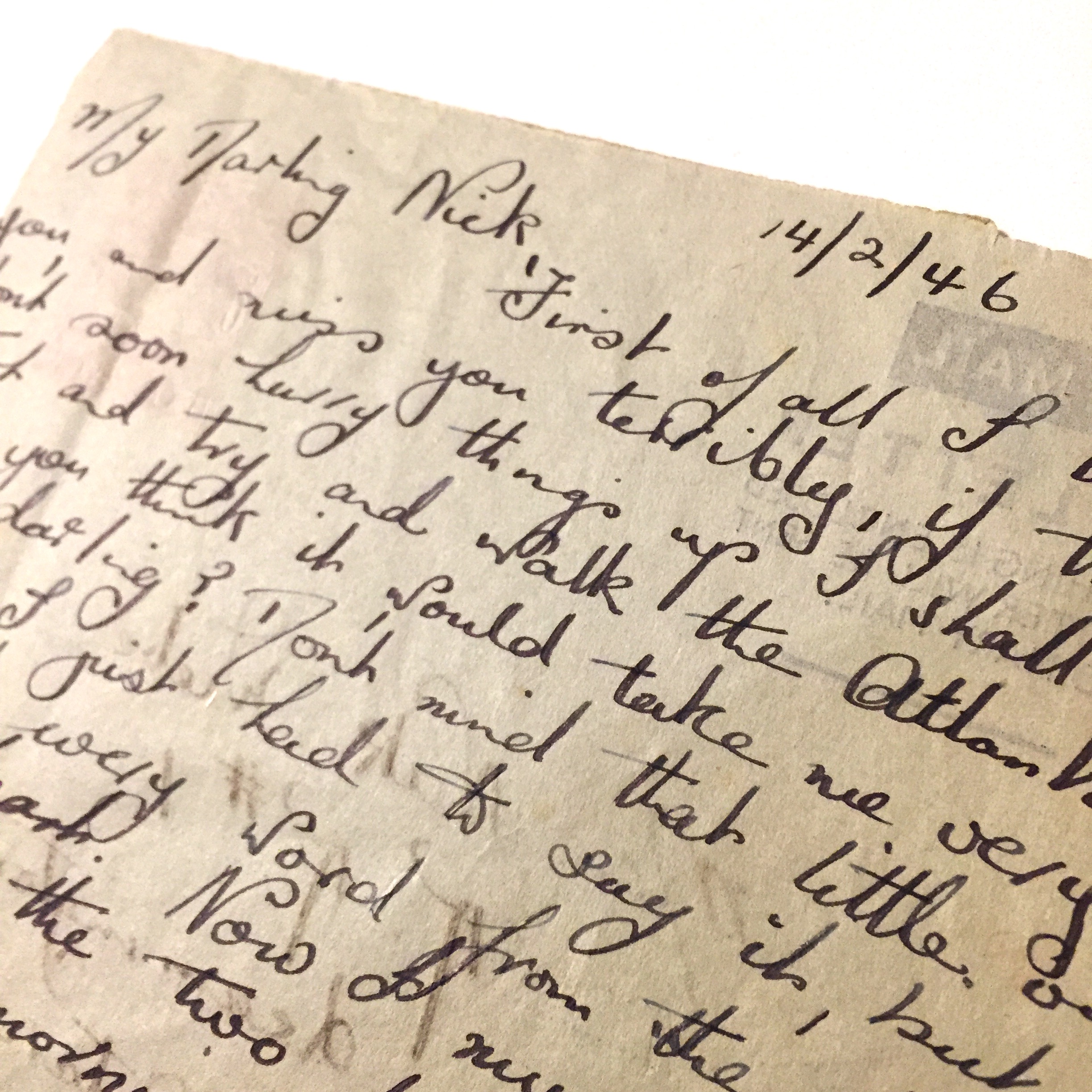

Right before she died my mother said the most amazing things. Look deep inside your heart and you will find the answer. Have the courage of your convictions, even if you are wrong. Have more faith in life. Have fun! And love and care will make everything all right. That one is most important. I still keep them with me: in my wallet, handwritten down.

RADECKI: When, do you think, was your mom proudest of you?

GOLD: One night, we had a real New York City evening planned. She came to meet me in the city to hear Michael Feinstein at the Regency. She came in by taxi from Queens. It was a real moment, to see us together in that way, dressed to the nines. We became elegant and adult together. Yet it was a moment of exquisite recognition of our separateness.

RADECKI: When were you proudest of your mom?

GOLD: Although we could get so angry with one another, there was never a time I was not proud of her. That may be my deepest connection to her. I always felt so proud of her.

RADECKI: You’ve credited your mother for recognizing that you had a future in food, and urging you to pursue that passion, even at a time when women were not prominent in professional kitchens. How did she see your path and encourage you to do what you loved?

GOLD: When I was in college at Tufts, I got a phone call from my mom. She had just heard an interview with the Hungarian restaurateur George Lang. That was the very first time I heard the idea of a restaurant consultant. I was a dual major in psych and education, but the food, she knew. I mean, she let me become a bartender at age sixteen, when she knew it wasn’t legal.

My mother was the one to see that I was spending more time cooking in the kitchen than working on my Masters degree. I dropped out of graduate school and became the first chef to New York Mayor Ed Koch when I was twenty-three. She enjoyed visiting me at Gracie Mansion, but felt bad about the grueling hours.

Again, always wanting to please. There was a restaurant, Villa Secondo, in Queens where my parents would always go. But, one day my mother called me to say, “Rozanne! Secondo, it’s gotten so much better!” Years later, I found out who the new chef was. It was Lidia Bastianich. She knew! My Mom just knew. She had that food sense.

RADECKI: In 2009, a few years after your mother’s death, you bought and saved over six thousand cookbooks from the library of Gourmet Magazine and donated them to the N.Y.U. Fales Library in your mother’s name. What does it mean to you to see her name Marion Gold on the nameplate of every book in that Gourmet collection?

GOLD: It felt so full circle…so right.