Gina's Aunt's Rice Pudding • Stacey Harwood-Lehman

Bretty Rawson

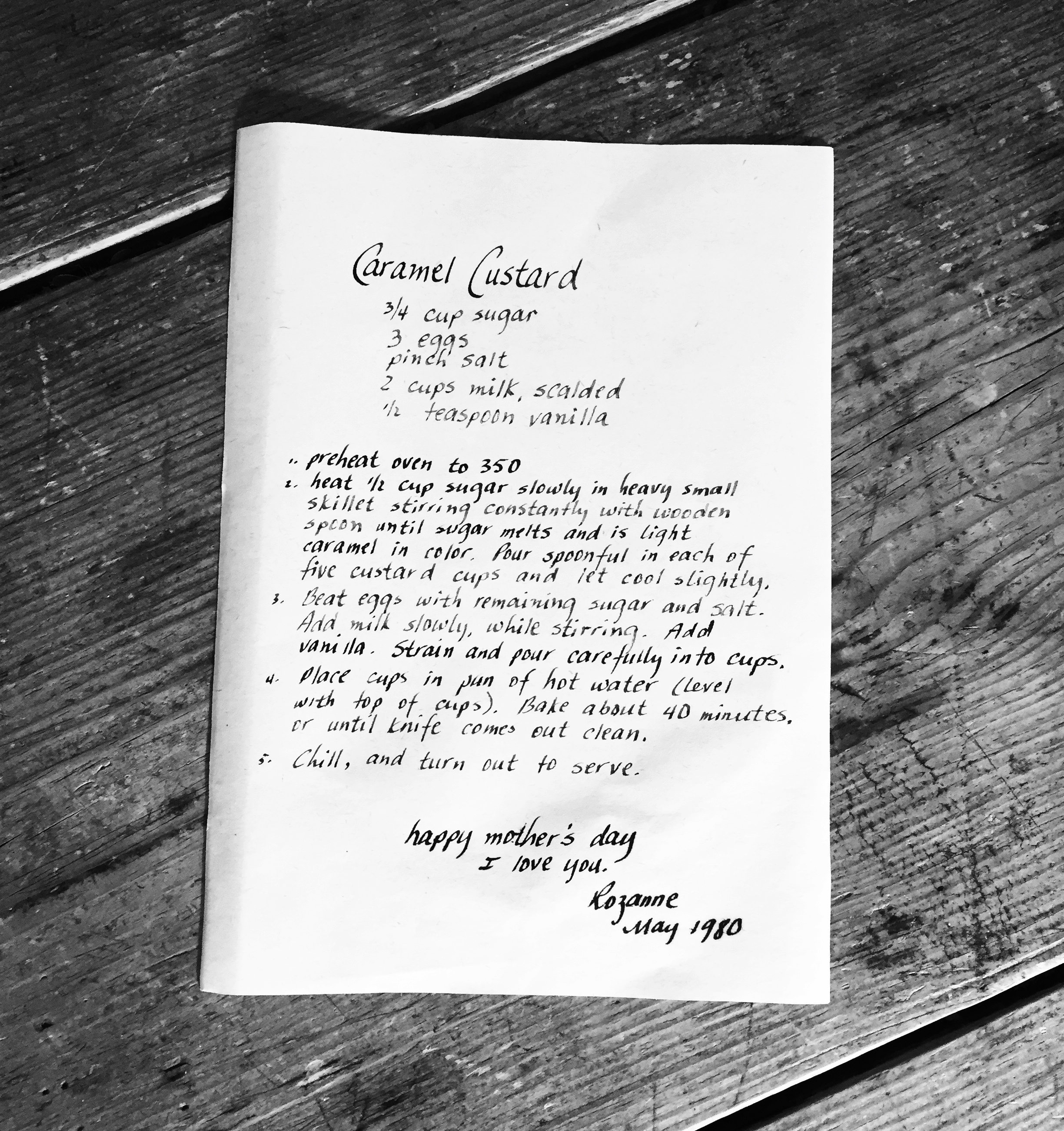

Note from curator Rozanne Gold: Gina’s Aunt’s Rice Pudding recipe comes to us by way of New York’s Poet Laureate of the Greenmarkets, Stacey Harwood-Lehman. I’m certain Stacey would love to garnish the rice pudding each season—perhaps a strawberry-rhubarb-ginger compote right now at the height of Spring? Poached pears and star anise in Fall? Either way, hers is a lovely story with a quixotic recipe scribbled in her own handwriting on a hotel pad of paper. I love it because it’s real…with a missing word or two, the very shorthand that makes cooking mysterious and sometimes serendipitous. Gina’s Aunt’s recipe is very sweet and could use a little scraping of fresh vanilla bean. It could feed your whole block. I messed around with a simple version of my own (see below), inspired by Stacey’s love of rice pudding!

Gina's Aunt's Rice Pudding By Stacey Harwood-Lehman

Gina and I had been working together for several years when she started dating Tony, a new employee in our agency’s IT department. Soon after Tony joined the staff, I noticed that the usually tech-savvy Gina seemed to be having an uncharacteristically difficult time mastering the new computer system and that Tony was making many visits to our floor to help her. Within a couple of months she announced their engagement. I was among the lucky few of her colleagues to be invited to the wedding.

At the time I was working in Albany, NY, as a policy analyst for the government agency that regulates gas, electric, water, and telephone utilities. I grew up in a suburb of New York City and had relocated to Albany to attend the state university. It wasn’t my intention to remain in Albany after college but there was a boyfriend and a job, so I stayed.

Gina’s work-station was situated near mine and we became friends even though when she joined the department she was only 19 — quite a bit younger than I was — and right out of secretarial school. She had a terrific fashion sense along with a lively sense of humor and an easy laugh. I was flattered that she liked to take a seat in my work cubicle to dish about office romances and such.

Gina liked to listen to the radio while she worked and I could hear her singing along, softly and slightly out of key, with the hits. A local rock station played the same two songs every Friday to usher in the weekend: Todd Rundgren’s “Bang on the Drum” (“I don’t wanna work; I wanna bang on the drum all day”) and Four in Legion’s “Party in My Pants,” the lyrics of which Gina heard as “There’s a party at my parents’, and you’re invited,” the perfect mondegreen to reveal her youthful innocence.

My proximity to Gina made me privy to her wedding plans. But before there was a wedding, there was a wedding shower to be held at the Italian Fraternal Club in Green Island, a small town roughly eight miles north of the state capitol. I was seated at a table of strangers, all of whom seemed to have known each other for decades. My attempts to enter the conversation mostly failed, until I learned that Gina’s aunt, who was seated across from me, had owned a small restaurant that she had recently closed in order to retire. The menu was red-sauce Italian and among her specialties was her rice pudding. I love rice pudding. Would she share her recipe?

Gina’s aunt was no-nonsense, someone you could imagine at the helm of a busy kitchen where everything was made from scratch and where the menu was likely the same from the day it opened until the day it closed. She explained that the recipe would feed a crowd, a large crowd, so unless I was planning to throw a big party, I shouldn’t bother with it. Never mind, I said. I want to give it try.

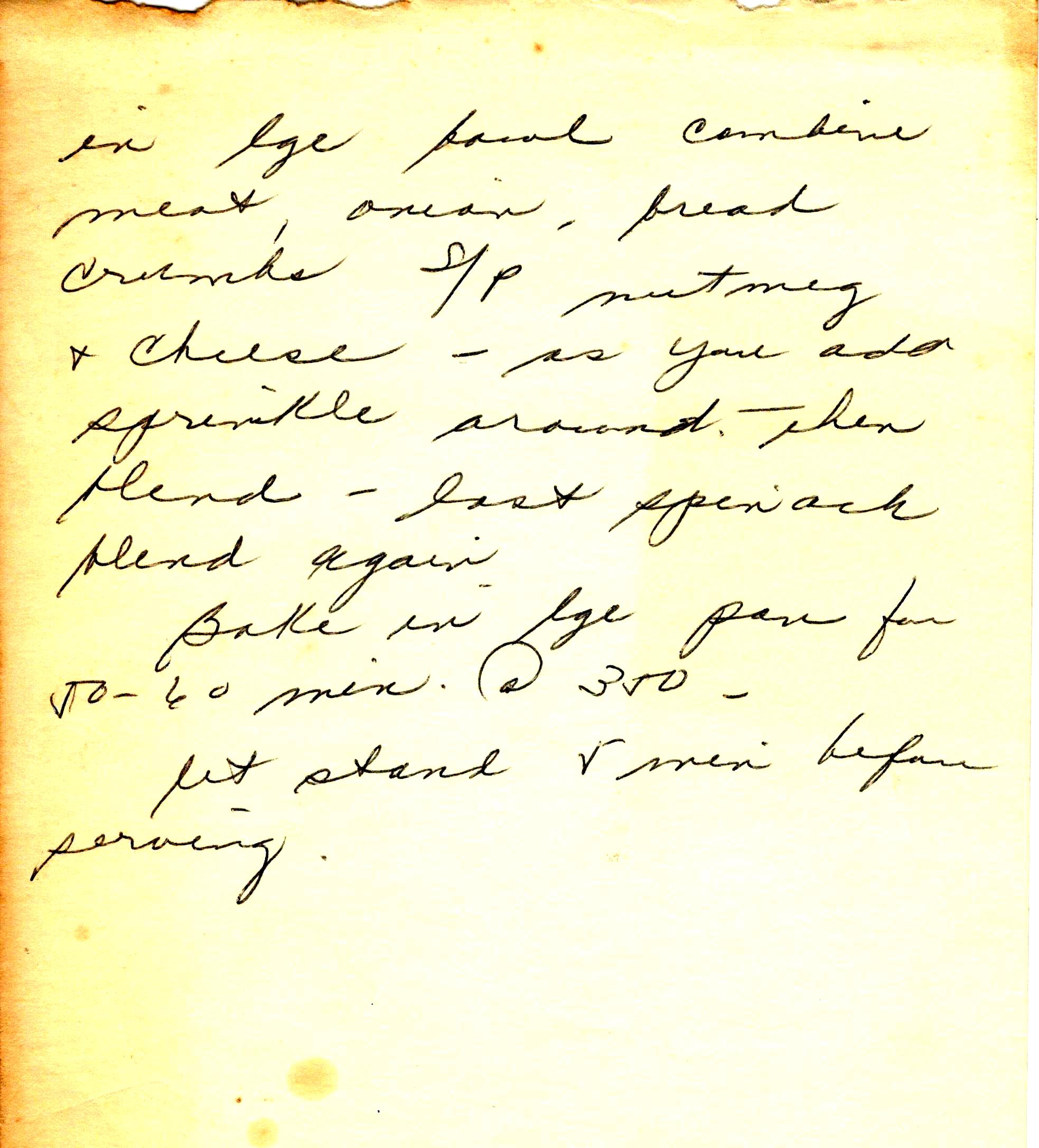

Something in her manner as she spoke, communicated doubt; doubt that I would be able to make a success of it. It was her rice pudding, after all. She dictated the recipe as I scribbled on a pad that I’d picked up from a hotel where I’d stayed during a recent trip.

That was decades ago. Gina had two children and divorced Tony. The recipe has been with me through several moves and life changes, stashed in an envelope stuffed with other recipes, some torn from magazines, others written hastily on scraps of paper.

When I ran into Gina’s aunt at the wedding, she asked if I had tried her recipe. I hadn’t. I was waiting for the right occasion. I’m still waiting.

Gina’s Aunt’s Rice Pudding

2 lbs. rice

½ gallon milk

5 cups sugar

18 eggs

½ box of raisins

1 stick butter

Cook rice 15 minutes. Drain in colander. Rinse. Beat eggs. Stir eggs over rice. Stir. Add sugar, stir, milk, stir. Put in stick of butter. Stir. Put in oven @350 covered with Reynolds wrap for 1 hour. Remove cover. Stir. Top w/nutmeg. Put back in oven until solid.

Creamy Rice Pudding

(without eggs)

1 quart 2%, or whole, milk

6 tablespoons sugar

¼ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon vanilla extract (or scraping of vanilla bean)

2/3 cup long or medium-grain rice

1/3 cup raisins

Grated nutmeg and/or cinnamon

Put milk in a 3-quart saucepan. Add sugar, salt, vanilla, and rice. Bring to a boil; lower heat to medium and boil, stirring 3 minutes. Lower heat to simmer (tiny bubbles steady on top). Cook 20 to 25 minutes, stirring frequently. Add raisins and cook several minutes until rice is very soft and mixture is thick but still soupy. Will firm upon cooling. Pour into a deep dish. Sprinkle with nutmeg and/or cinnamon. Cover and chill. Serves 4 to 6