A Legacy of Travel • A Conversation with Christian Corollo, Past Present Project

Bretty Rawson

BY CARLY BUTLER

After crossing paths with Christian on Instagram, I could tell that Christian and I had a lot in common. Not only was he recreating photos that his grandfather had taken 30 years earlier, but there were also ties to the grandmother's handwritten journals that made his journey so fascinating. Photographer and travel blogger, Christian created the Past Present Project and I had the chance to ask him a few questions about what kind of an impact these family heirlooms have had on his life.

CARLY: How did you come across this heirloom?

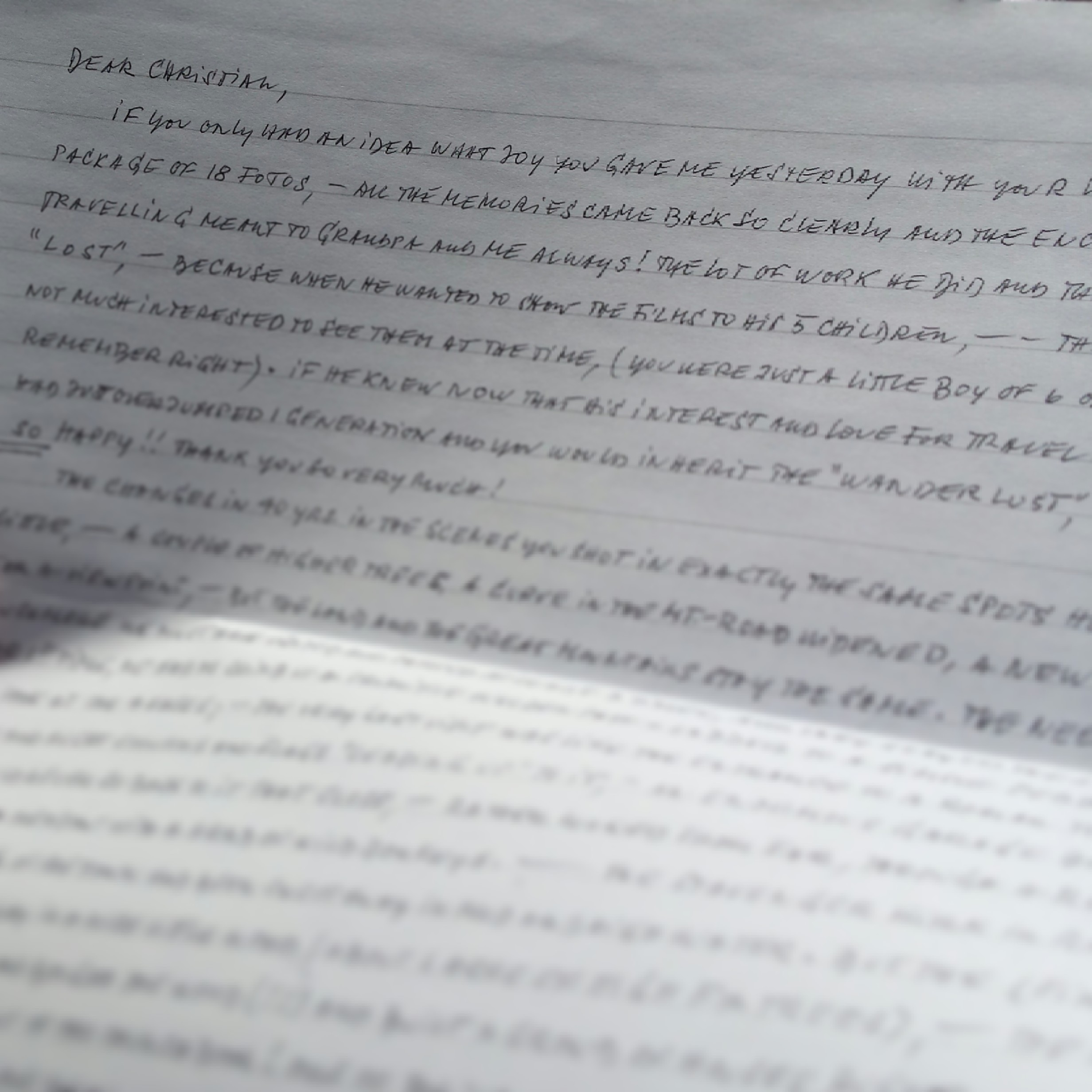

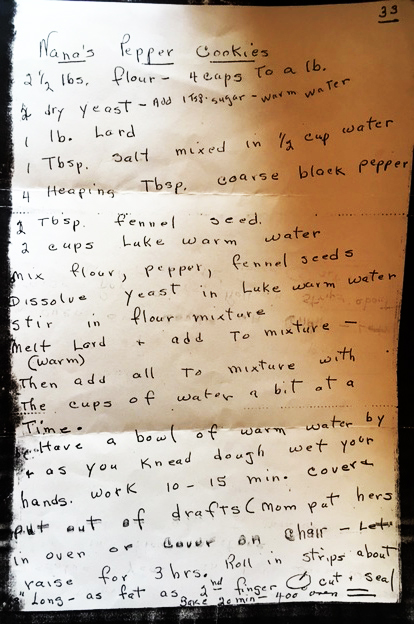

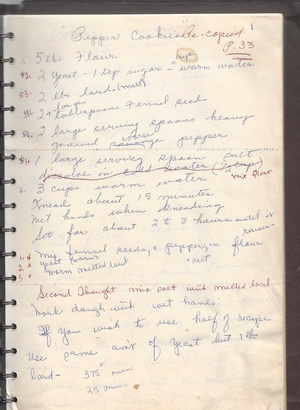

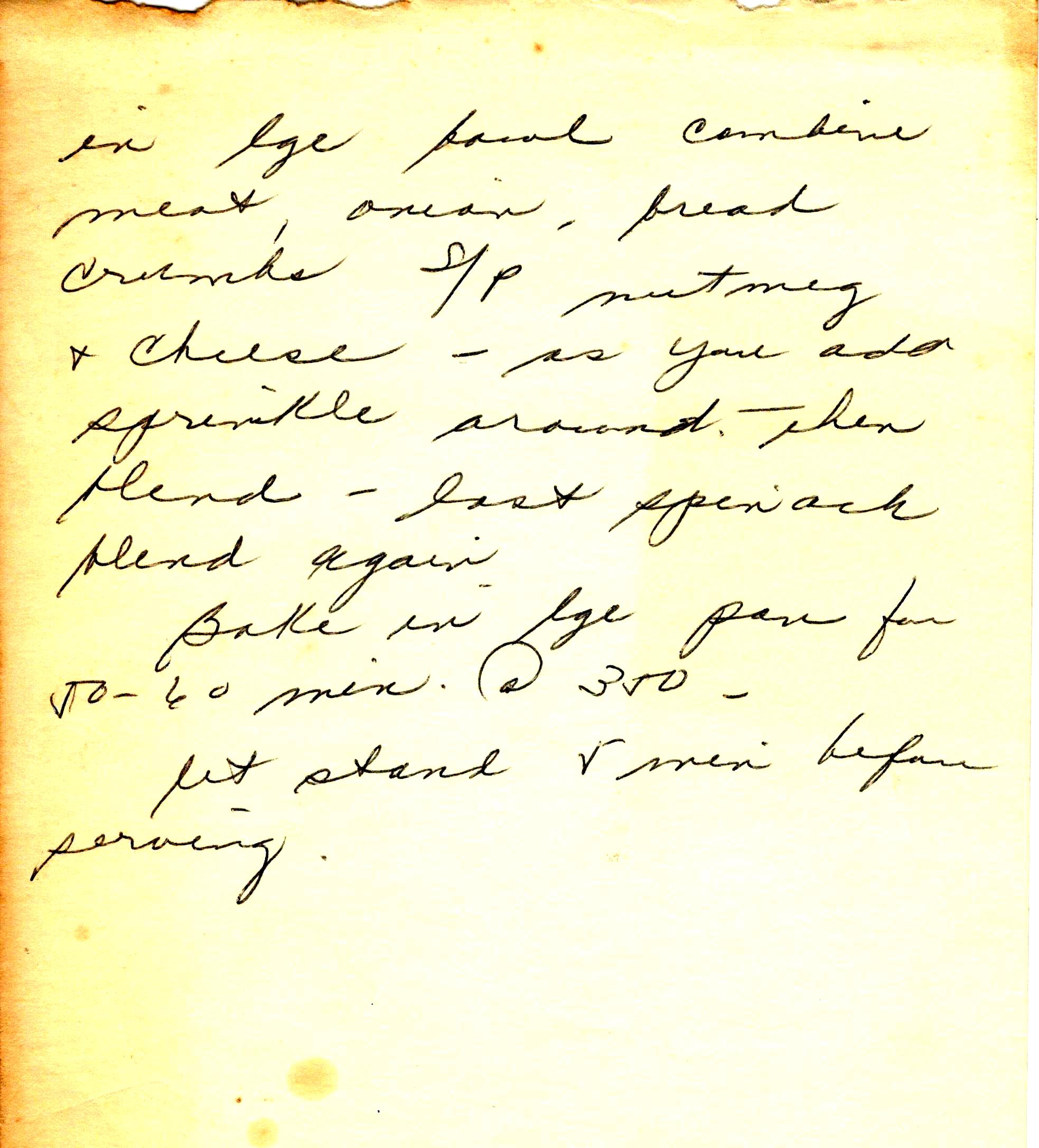

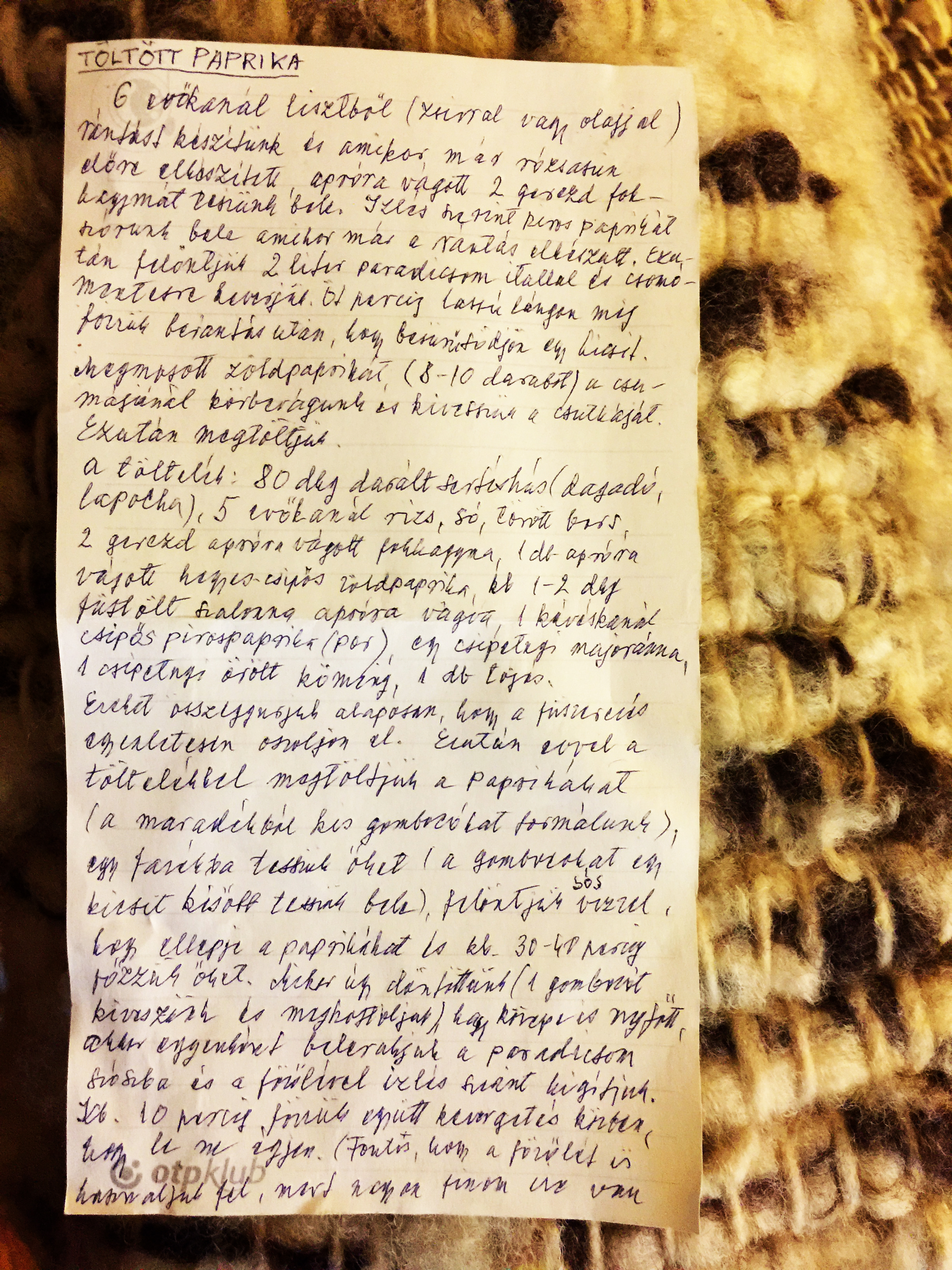

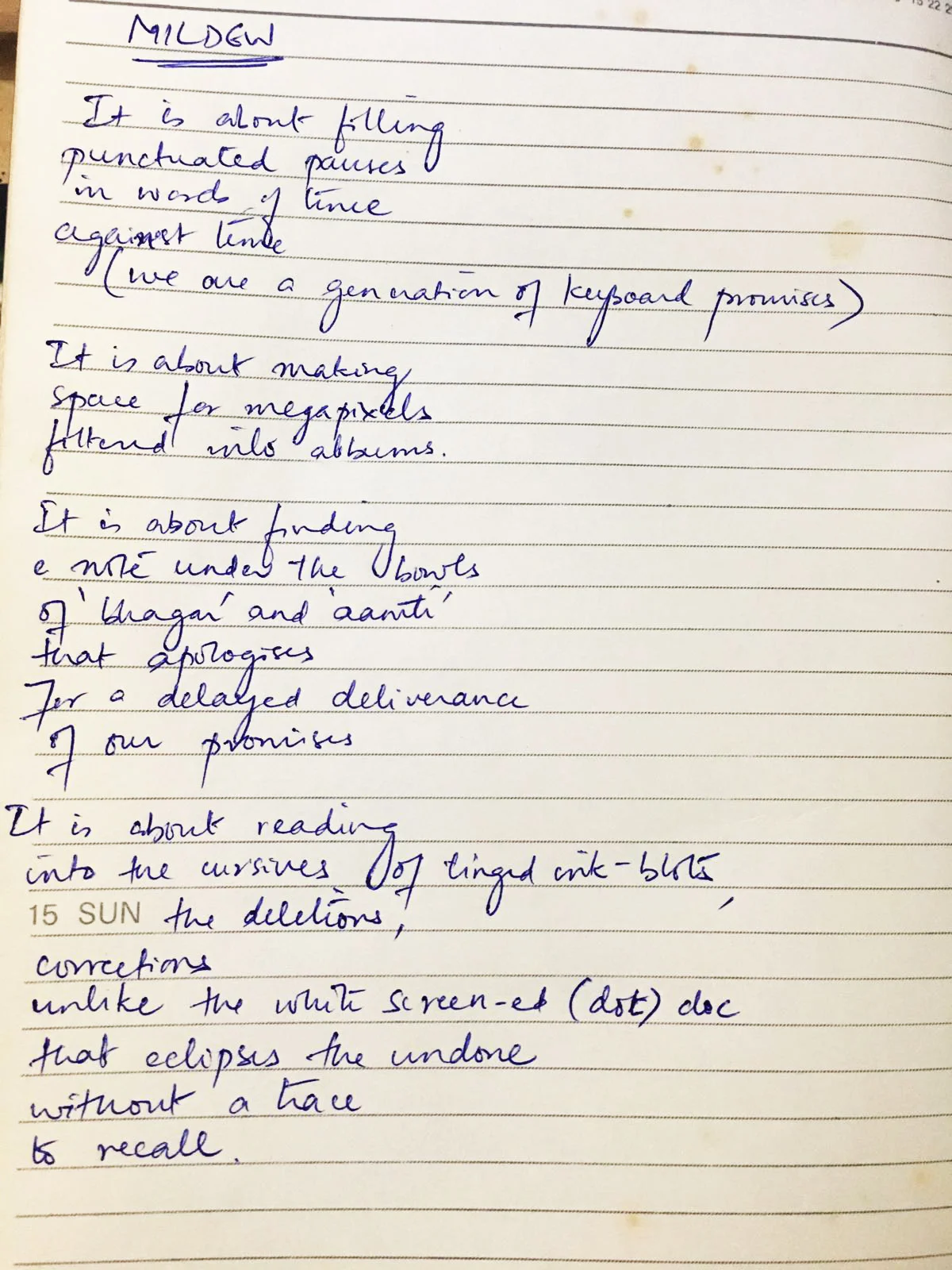

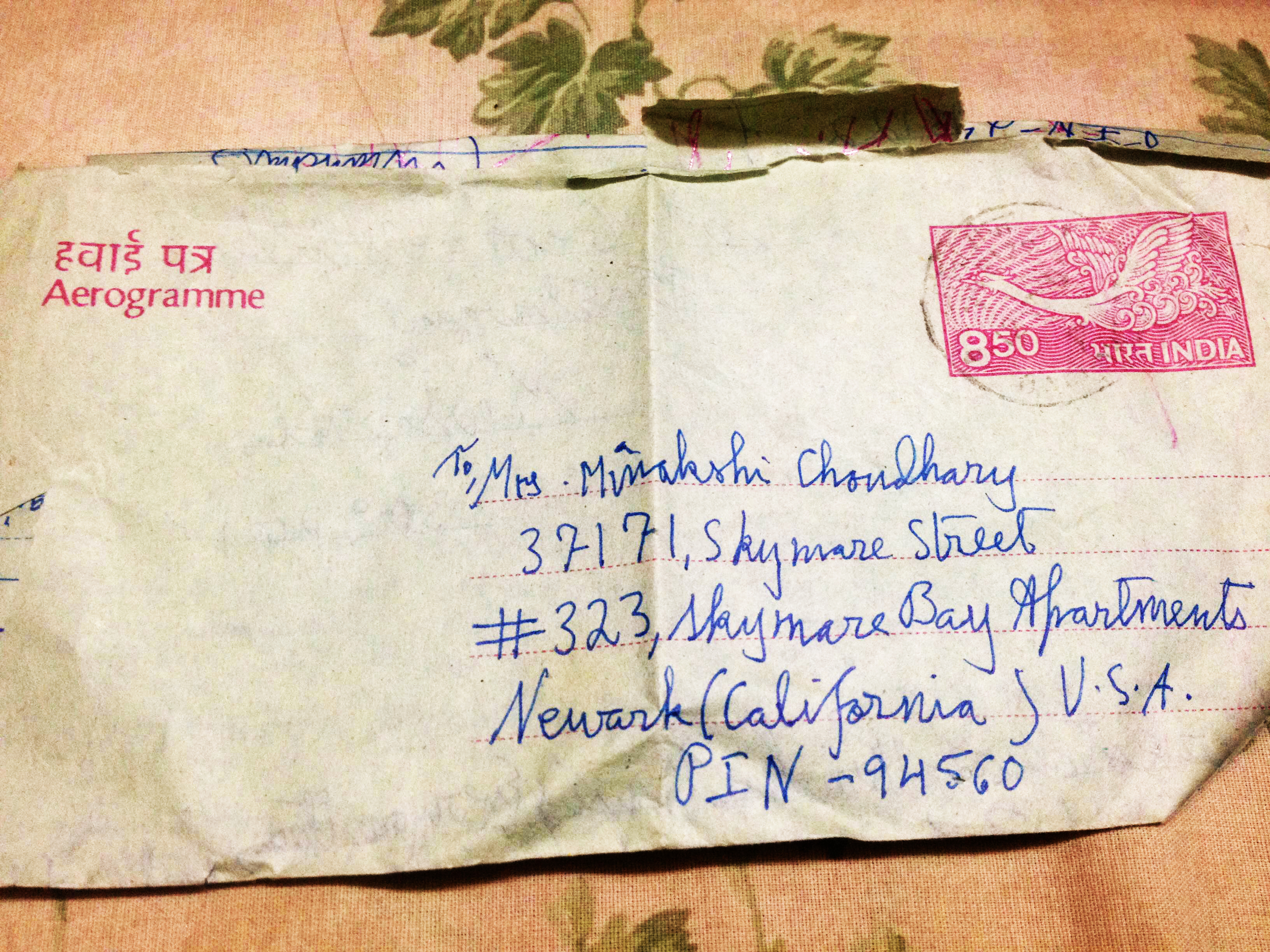

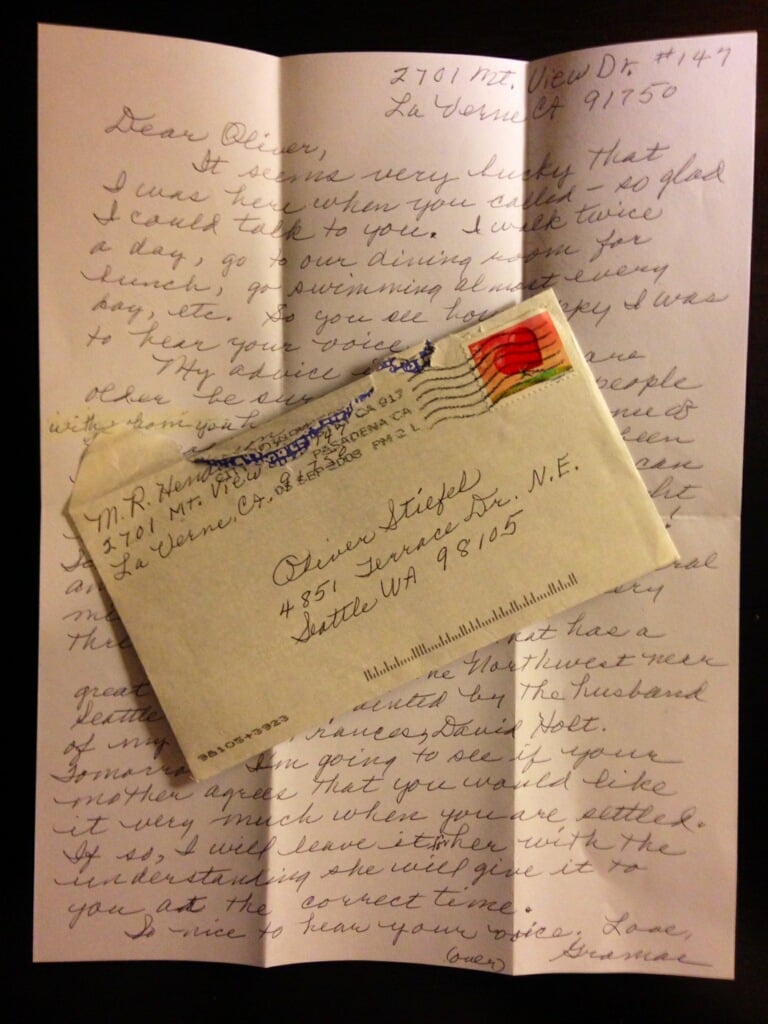

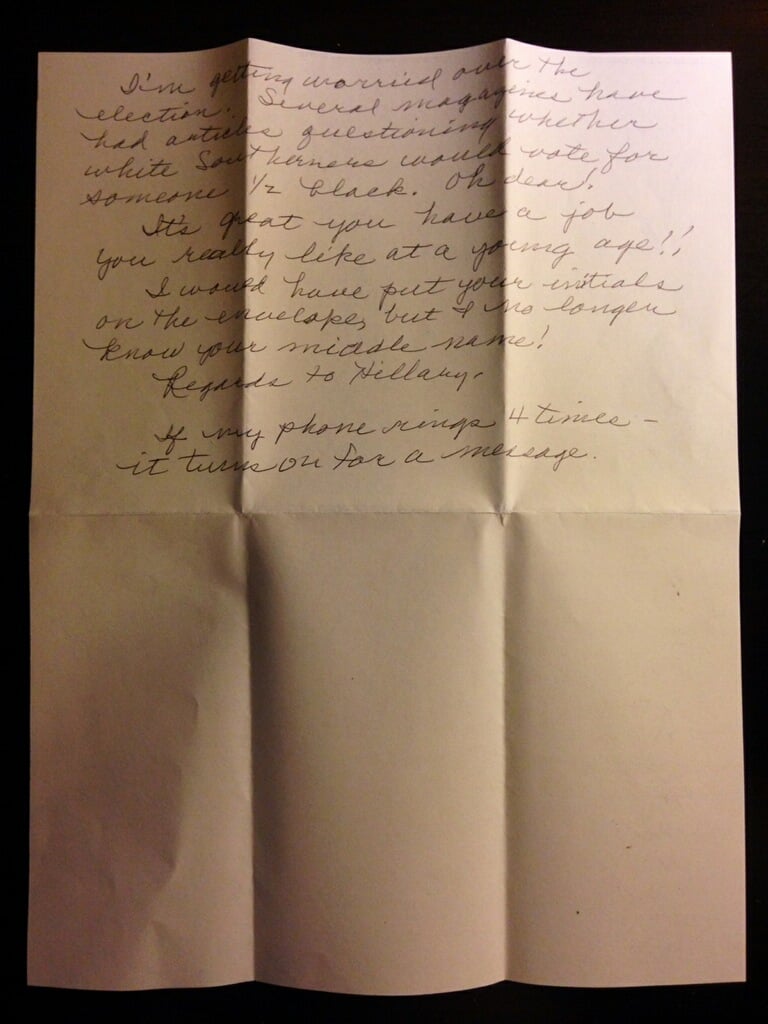

CHRISTIAN: It all started in August of 2012 during a visit with my 99-year-old grandmother in Florida. After telling her about my relatively new love of travel, she showed me the travel journals from all of the trips she and my grandfather had taken between 1973 and 2003. I was fascinated by her detailed accounts of their journeys, including names of people they met and exact locations of places they stayed, and eventually had the courage to ask if I could keep such a treasured possession. Knowing that her journals would not be of interest to anyone after she passed away, she was delighted to hand them over to someone who would treasure them beyond her. I left Florida with over 20 of her thirty journals.

CARLY: What does it mean to you to have this piece of handwritten work?

CHRISTIAN: I could sense how important these journals are to my grandmother — filled with memories of moments shared with my grandfather, experiences that come flooding back when she reads the words contained inside, and a legacy of travel. She has expressed this legacy of travel to me on many occasions and how proud my grandfather would be that I’m carrying it on in our family. She has also told me that their trips together are when they were the happiest. This is why I’ve felt the conviction to not only continue the legacy of travel they began, but share the words and moments of the most treasured times of their life.

CARLY: What has it inspired in you?

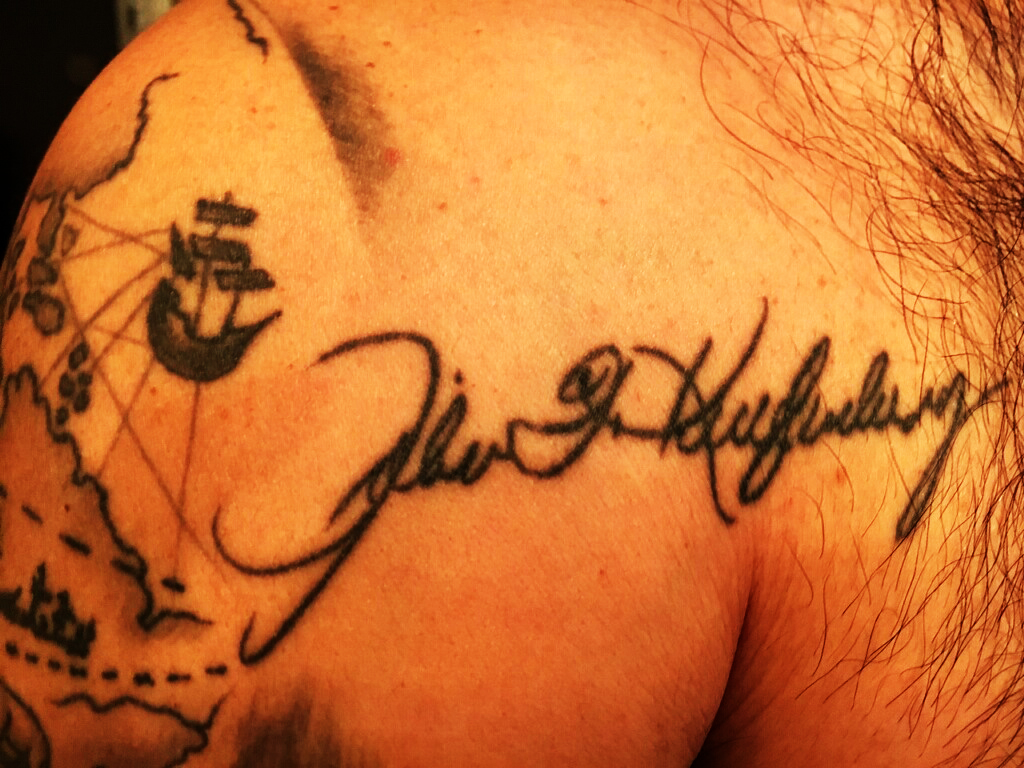

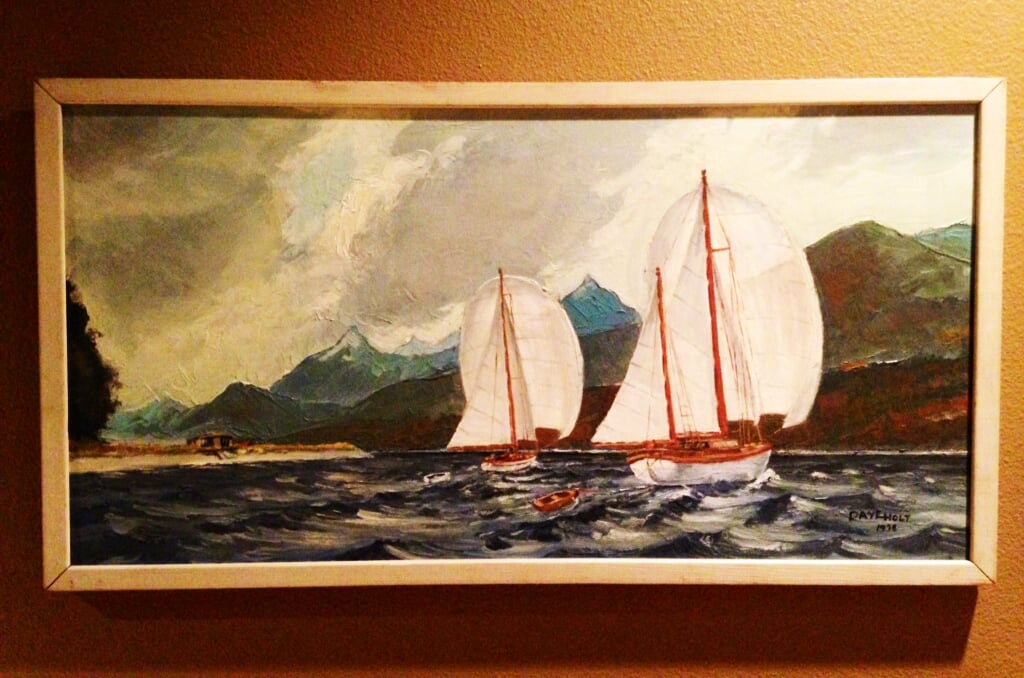

CHRISTIAN: Little did I know in 2012 that with the combination of her journals and my grandfather’s travel photographs, I would embark on my own journey of retracing their steps and stand in the same places they did so long ago. If not for her travel journals, I never would have discovered the exact locations of so many of my grandfather’s photographs or known the names and met for myself the people in his images.

Valhalla Pier in South Lake Tahoe, California | June 1981 & May 2015

Excerpt from my grandmother’s travel journal on June 9th, 1981: “Walked down to the lake – a vast expanse of quietly lapping water, brilliant sun, and a small sand beach before the ‘Jeffrey’ pine woods.”

Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, California | April 1979 & May 2011

Excerpt from my grandmother’s travel journal on April 27th, 1979: “There was an earthquake at that time in the middle of San Francisco! We didn’t feel it – were much too busy finding our way through town to the Presidio, a big military reservation. The scenic route lead right through it, to Fort Point, directly under the Golden Gate Bridge. Going on along the shore-drive, high above the blinding shimmering-white sea against the sun, along funny colorful small houses.

To see more of the Past Present Project, visit Christian's lovely website: www.pastpresentproject.com.